Department History

The Practice of Objects Conservation in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1870–2011

Since its founding in 1870, the Museum has dedicated substantial resources to the preservation and technical study of its collections. Built upon the efforts of a diverse assemblage of craftspeople, restorers, scientists, security guards, directors, and curators working in isolated workshops, laboratories, and offices, the discipline of conservation gradually attained professional stature at the Museum, culminating in 1942 in the creation of a Sub-Department of Conservation and Technical Research. Currently, more than twenty academically trained conservation professionals, specializing in three-dimensional works of all kinds, are situated in dedicated studios and laboratories, collaborating closely with curators, scientists, mount makers, registrars, collections and facilities managers, and other museum specialists.

In 1968, the Museum acquired its first x-ray unit powerful enough to radiograph materials of high atomic weight, such as stone or metal (figure 15). This acquisition was funded by Museum trustee Charles Wrightsman, motivated in part by the potential benefit to the NYU students that were beginning to populate the department as interns and fellows. Lawrence J. Majewski, the second Chairman of the NYU's Conservation Center, had been a fellow in the Technical Laboratory in 1952, and the relationship between the Conservation Center and the Museum established early on continues to be a close one.

I. Ancient History: "They Also Serve" (1870–1942)

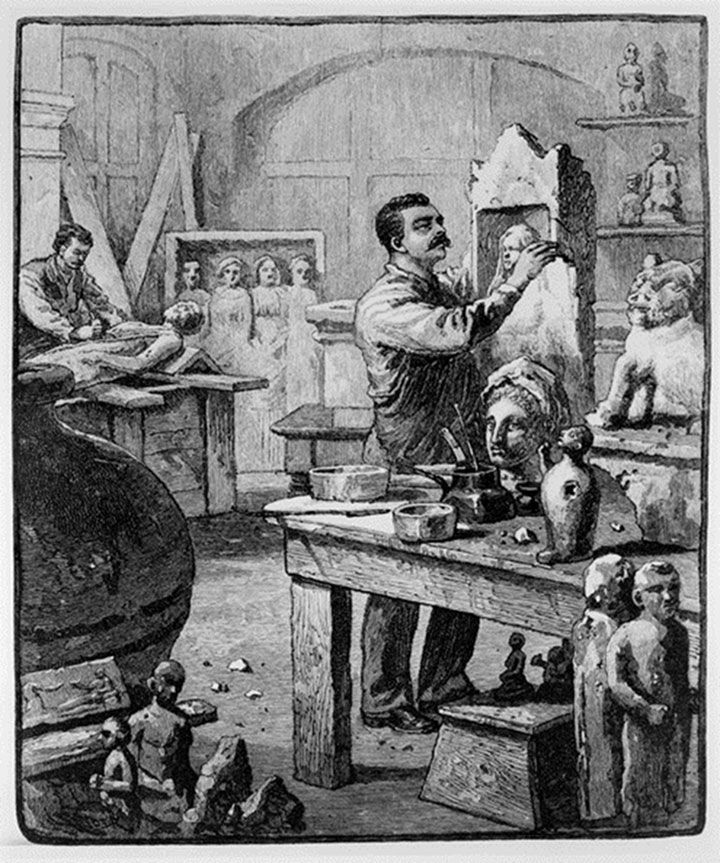

The Museum's early directors participated in conservation matters to a striking degree. Luigi di Cesnola, the first director (1879–1904), personally supervised the restoration of Cypriot antiquities previously purchased from him by the Museum. In 1880, he became embroiled in controversy, along with Charles Balliard (Figure 1), the Museum's first truly recognizable figure in the history of restoration, as accusations in the press charged that the newly installed Cypriot sculptures were overly restored or were pastiches assembled from unrelated fragments.

A committee named by the Museum to investigate these allegations followed a methodology that accords well with the course that would be followed today: "We have invited and received the valuable assistance of well-known sculptors and practical stone cutters and carvers, have taken the opinion of scholars, have made microscopic, chemical, and other examinations of the surfaces, and have subjected some of the repaired objects to prolonged baths, taken them to pieces, and verified the relation of the fractured surfaces. We have had before us original photographs of the objects, taken at the place of discovery, and at later periods, and abundant evidence of their history down to and during the process of repairing and arranging for exhibition in the present Museum building."[1]

Cesnola was vindicated at the time, but subsequent developments and recent re-examinations point to a certain degree of misrepresentation. An early voice for the appreciation of the original or as-excavated surface for its artistic and scientific value was John L. Myres, who described in several articles as well as in his 1914 Handbook of the Cesnola Collection the various steps taken to reverse some of Balliard's embellishments. What constitutes an acceptable degree of restoration is a question that is continually revisited by conservators and curators to this day.

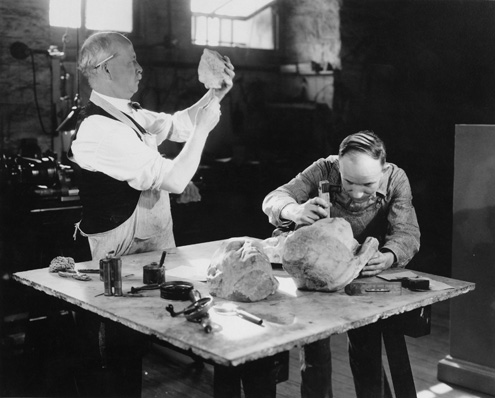

During his twenty-one-year tenure as the Museum's third director, Edward Robinson (1858–1931) brought new analytical and imaging tools to bear on questions of authenticity, dating, and the extent of prior restorations (Figure 2).

The expanding role of science is seen in Robinson's call in 1925 for a national laboratory to ensure the highest-quality scientific treatment of works of art, and in his engagement of electrochemist Colin G. Fink (1881–1953) as consultant, to investigate the deterioration and preservation of archaeological bronzes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Harpokrates. Egyptian, Ptolemaic–Roman Period (332 B.C.–A.D.330). Copper alloy. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. S. W. Straus, 1925 (25.184.19), before and after electrolytic treatment by Colin Fink.

Robinson clearly understood the role of environment in preservation: "It is a general impression among visitors to museums that once a work of art has been properly installed, once it has been set on a pedestal or hung upon a wall, and more especially if it has been protected by glass, its life is assured for an indefinite future. So far is this from being the fact, however, that exactly the contrary might almost be said to be true. Many objects bring with them the germs of deterioration if not of actual destruction, others though sound when they are received are highly sensitive to relative degrees of heat and cold, moisture and dryness, and to the atmospheric impurities of our modern cities, never so serious a menace as they are today."[2]

Figure 4. Archival film footage from 1924, showing Herbert E. Winlock at Thebes, applying wax and removing excess during consolidation of a wooden coffin.

Robinson's successor, Egyptologist Herbert E. Winlock (1884–1950), was a shrewd observer of ancient manufacture and an active conservation practitioner, treating works in the field and in the Museum (Figure 4). He also hired the Museum's first staff chemist, Arthur H. Kopp (1900–1938) (Figure 5) in 1932, whose multifaceted labors as scientist and restorer are attested to in his meticulous laboratory notebooks.

Figure 5. "Metal Repair Shop Wing B Room 131 Basement Floor," October 26, 1936, detail. The man pictured here lacquering is almost certainly Arthur H. Kopp.

For the most part, however, during the first decades of the twentieth century, restoration, mount making, and installation fell largely to repair shops staffed by mostly anonymous craftsmen (Figures 6–8); only a few of which can be identified and credited today.

Figure 6. "Repair Shop," November 4, 1936, with anthropoid coffin of Harmose (36.3.172).

Figure 7. "Repair Shop Wing B Room 135 Basement Floor," January, 30, 1928, detail. In this overcrowded staged photograph, only two tasks can be clearly identified: drilling a relief (far right) and reassembling a ceramic vessel (front, left). An Attic volute-krater (27.122.8) acquired one year earlier, is in front of window at left.

Figure 8. "Repair Shop Wing B Room 135 Basement Floor," October 6, 1926, showing Classical stone sculpture being fitted for mounting.

Departmental records of a "Mr. Smith" known to have helped Winlock clean copper and bronze objects most probably refer to Arthur Smith, hired as foreman of the repair shops in 1927 and retired in 1941.

Figure 9. "Egyptian Tank Room Wing A Room 104 Basement Floor," October 24, 1930, showing Chris Watt with a granite figure of Hatshepsut (29.3.1) during restoration.

Chris Watt (Figure 9), received little, if any, public recognition for his reassembly of the Museum's monumental Egyptian stone sculptures of Hatshepsut though his skill and dedication were praised in correspondence between Winlock and fellow curator Ambrose Lansing.

In 1940, Francis Henry Taylor (1903–1957), the Museum's fifth director, arrived from the Worcester Art Museum, bringing with him a shared tradition of conservation innovation centered on Harvard's Fogg Art Museum (Figure 10). He soon requested a curatorial investigation into the Museum's restoration practices.

Left: Figure 10. Francis Henry Taylor (left), in the Gubbio Studiolo, April 1952.

According to the resultant report: "general repairs, including metal, stone, ceramics, and furniture, [are] carried out . . . by men for the most part self-trained, having advanced from general services, . . . directed by the Building Superintendent on the same basis as house mechanics, such as electricians, plumbers, masons, carpenters, and machinists."[3] The committee also noted "Quality of work generally satisfactory to curators. Working conditions poor. Technical direction, as distinct from mechanical supervision, practically non-existent."[4] In late 1941, Taylor hired Murray Pease (1903–1964), a Fogg alumnus, as consultant, charging him with the task of organizing and directing a general department for conservation (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Murray Pease radiographing a painting, October 1954(?).

II. The Middle Ages (1942–76): Consolidation and Dissolution

In 1942, the above-mentioned Sub-Department of Conservation and Technical Research was established, with Pease as associate curator. In the following years, Pease and Taylor laid foundations for modern conservation practice through the introduction of standardized "request for treatment" forms, protocols for documentation, condition checks for outgoing loans, and proper handling guidelines, which formed the basis of The Care and Handling of Art Objects, published by registrar Robert Sugden in 1946. The 1940s also saw publication of several articles on gallery lighting by Museum business administrator Lawrence S. Harrison. In 1949, raised to curatorial standing and full departmental status, the sub-department was renamed Technical Laboratory, and seven years later Pease was appointed Conservator, the first time this title was used in the Museum. Examination by conservation staff of loan objects upon arrival in the Museum and before repacking became the norm in 1960.

Figure 12. Dietrich von Bothmer, then Assistant Curator, and Frank Falson, a security guard turned repairer, reassembling an ancient lekythos, a gift to President Harry S. Truman by the Greek Government that had been damaged during shipping, 1949.

Trained as a paintings conservator, Pease made few changes in the practice of objects conservation. Having combined the existing, disparate workshops, he still supervised the same autodidact craftsmen that had worked in the Museum for many years (Figure 12), in addition to several newly hired painting conservators.

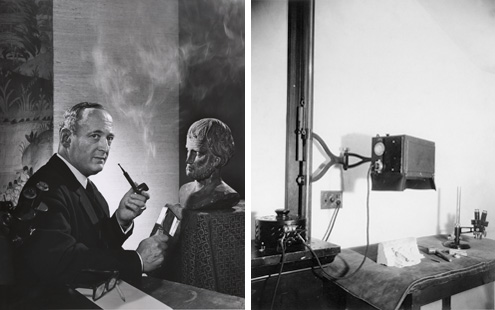

Figure 13. James J. Rorimer, 1964. Rorimer's persona as a man of science is vividly captured in this work by legendary portrait photographer Yousef Karsh (1908–2002). © Estate of Yousuf Karsh. View in slideshow. Figure 14. "Ultra Violet Ray Room Wing F Room 107 Basement Floor," July 2, 1931, (detail).

James J. Rorimer (1905–1966), a curator since 1927 (and later Director from 1950–65) (Figure 13), had been greatly encouraged in his scientific investigation of ultraviolet examination by Robinson (Figure 14). Exposed to conservation practices as a Harvard undergraduate, Rorimer was also the son of an influential designer and craftsman, who instilled in him as a youth the skills of a handworker. Rorimer closely supervised conservation treatments and, like Winlock, he was an enthusiastic practitioner. From 1938–46, every Monday when The Cloisters was closed, Rorimer worked in the galleries with Charles Langlais, a "restorer of stone, etc." hired in 1929, removing overpaint from an important French fourteenth-century limestone Madonna and Child, that is, except for Mary's face, which Rorimer had already cleaned on his own.

The craftsmen (and women, who worked on textiles and upholstery) from the repair shops were not mentioned in the Museum's annual report until the early 1960s, in spite of Pease's attempts to have Taylor increase salaries of these skilled workers, many of whom were engaged only on a part-time basis, and to raise their status to that of their curatorial counterparts. Pease also advocated for the emerging profession as a founding member of what became the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC), and he headed the committee that drew up guidelines for basic standards of professional practice and ethics accepted by the IIC membership in 1963. Full professionalization of the discipline required professionally trained objects conservators. It was not until 1960, after the demise of the Fogg's training program for painting conservators, that the first graduate-level training for conservators of three-dimensional objects, textiles, and works on paper, as well as paintings, was founded at New York University (NYU). The students were offered an interdisciplinary education combining art history and archaeology, natural sciences, historic technology, and practical experience in treating works of art. Although Pease long stressed the need for scientific staff, as had the curatorial committee that led to his hiring in 1941, it was only in 1970, after Pease's death, that the Museum engaged a research chemist, Pieter Meyers, who was joined by several colleagues in the early years of the 1970s. In addition, new analytical equipment was purchased.

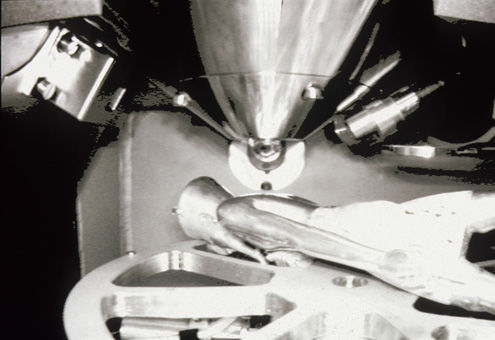

In 1968, the Museum acquired its first X-ray unit powerful enough to radiograph materials of high atomic weight, such as stone or metal (Figure 15). This acquisition was funded by Museum trustee Charles Wrightsman, motivated in part by the potential benefit to the NYU students that were beginning to populate the department as interns and fellows. Lawrence J. Majewski, the second Chairman of the NYU's Conservation Center had been a fellow in the Technical Laboratory in 1952, and the relationship between the Conservation Center and the Museum established early on continues to be a close one.

Left: Figure 15. Kate Lefferts and Pat Staunton with recently purchased high-kilovoltage X-ray unit, 1968.

The 1961 appointment of Hubert von Sonnenberg as Conservator of Paintings in the Department of European Paintings marks the beginning of a transition that continued into the first half of the 1970s with the creation of specialized departments organized by media, with an additional department today for scientific research. When Pease died in 1964 he was succeeded Kate Lefferts, herself largely self-taught. The years immediately following Lefferts retirement in 1970 were characterized by a lack of direction and professional development.

III. The Renaissance (1976–2003): An Emerging Profession

In 1976, recognizing a compelling need to hire professional conservation and installation staff for the second phase in a massive reinstallation of the Egyptian collection comprising approximately thirty thousand objects, James H. Frantz (Figure 16), an alumnus of the NYU graduate program, was named Conservator in Charge of the Department of Objects Conservation.

Figure 16. James H. Frantz, Conservator in Charge from 1976–2003, in the Fifth Floor studios of the Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, 1994.

During his twenty-seven-year tenure in this position, Frantz transformed the department and influenced the practice of conservation and scientific research in the Museum as a whole.

Additional professional conservators were hired, along with skilled installer/mount makers, whose contributions—producing exhibition, storage, and travel mounts that conform to conservation standards—assumed great importance (Figure 17). New scientists also joined the department and new analytical equipment, including a scanning electron microscope, was purchased (Figure 18).

Figure 17. Installer Sandy Walcott manufacturing brass mount, 1988.

Figure 18. Gold statuette of the god Amun (26.7.1412) in the scanning electron microscope vacuum chamber during imaging and analysis.

In the Museum's Annual Report for the years 1980–81, departmental staff numbered more than forty, including sixteen conservators, eight restorers, twelve installers, two scientists, plus a small administrative staff. This growth in expertise and equipment was facilitated by the financial support and advocacy within the Museum provided by the Department's newly named visiting committee.

The completion of the Egyptian Wing was followed by the reinstallation, in turn, of all curatorial collections as well architectural expansions such as the creation of the Rockefeller Wing housing arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. These capital projects along with the Museum's ever-more ambitious exhibition schedule, continued to occupy the department's staff, which as the work force expanded and restorers of earlier generations retired, was made up increasingly of professionally trained conservators, including specialists in furniture, historic interiors, and upholstery conservation (Figure 19).

With the renewal of the Museum's former archaeological concession at Lisht (Egypt), later expanded to Dahshur, departmental conservators have become active participants on excavations there and elsewhere in Egypt, Europe, the Near East, and South America (Figure 20).

Figure 19. Upholstery conservator Kate Gill working on a corner settee from the Seehof garden furniture, 1988.

Figure 20. Conservator Ann Heywood consolidating pigment on relief fragment from the temple of Amenemhat III, Dahshur (Egypt), late 1990s.

In 1992, the department moved from a sprawling, impractical space cobbled together from old workshops to the Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, a newly designed facility integrating studios and laboratories (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Ground floor studios of the Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, 1994.

The Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation at the Cloisters was completed in 2002. The Center expanded its role in the training of future conservators and conservation scientists, serving as a formal and informal classroom for beginning and advanced NYU conservation students, and hosting interns, fellows, and visiting scholars from around the globe, many supported by the D. W. Frohlich Charitable Trust, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Sherman Fairchild Foundation

IV. Modern and Contemporary (2003–present): Specialization and Collaboration

Most of the Museum's analytical equipment and its resident scientists were part of the Department of Objects Conservation until 2003. In that year, in recognition of the expanding role of conservation scientists in museums and in order to provide scientific support to the Museum's conservation departments dedicated to paintings, works on paper, photographs, textiles and costumes, and arms and armor, the Museum established an independent Department of Scientific Research. In shared laboratories renovated in 2004, object conservators still carry out instrumental investigation and analysis, dividing their efforts between treatment-related and technological questions, well supported and supplemented through their collaboration with the Museum's research scientists, as both departments continue to expand their imaging and analytical capabilities.

For many years, the Department of Objects Conservation has regularly housed conservators with a broad range of expertise. The year 2004 saw the addition of a dedicated studio for stained glass to accommodate the Museum's first stained glass conservator. In 2008, following the retirement of the former conservator of musical instruments, primary responsibility for the physical care and technical study of that collection was transferred to a musical instruments conservator based in Objects Conservation.

Further Reading

Becker, Lawrence, and Deborah Schorsch. "The Practice of Objects Conservation in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1870–1942)." In Metropolitan Museum Studies in Art, Science, and Technology I (2010), 11–37.

Howe, Winifred E. A History of The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Vol. 1, with a Chapter on the Early Institutions of Art in New York. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1913.

Howe, Winifred E. A History of The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Vol. 2, 1905–1941, Problems and Principles in a Period of Expansion. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1913.

Kargère, Lucretia, and Michele Marincola. "Conservation in Context: The Examination and Treatment of Medieval Polychrome Wood Sculpture in America." In Metropolitan Museum Studies in Art, Science and Technology 2 (2014), 11‒49.

[1] Quoted in Winifred E. Howe, A History of The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Vol. 1, with a Chapter on the Early Institutions of Art in New York (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1913), 222–23.

[2] Edward Robinson, "Introduction" in Colin G. Fink and Charles T. Eldridge, The Restoration of Ancient Bronzes and Other Alloys (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1925), 3–6.

[3] As paraphrased in a later report by Murray Pease, "Report to the Director on the Technical Laboratory," unpublished report [1951], departmental files, The Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1.

[4] Letter from Ambrose Lansing to Francis Henry Taylor, May 5, 1941, departmental files, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.