In conjunction with Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection, Native artists, authors, community members, curators, and historians have responded to twenty eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Euro-American works in the American Wing’s collection.

Offering a multiplicity of voices and perspectives, the twenty-four contributors present alternative narratives and broaden our understanding of American art and history.

James Thomas Stevens and Jackson Polys on Hiawatha

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (American, 1848–1907). Hiawatha, 1871–72, carved 1874. Marble, 60 x 34 1/2 x 37 1/4 in. (152.4 x 87.6 x 94.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Diane, Daniel, and Mathew Wolf, in memory of Catherine Hoover Voorsanger, 2001 (2001.641)

Looking at Hiawatha, my thoughts run to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, not in appearance but in overall composition. Shelley never used the word “monster” for her nature-loving “creature,” but Frankenstein—like Hiawatha—is an admixture of parts. Saint-Gaudens’s figure was inspired by Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha,” which drew on Henry Schoolcraft’s Algic Researches (1839) and its stories of the Anishinaabe of the upper Great Lakes. But Longfellow employed the name of an Iroquoian cultural figure, believing Hiawatha to be “another name for the same personage [Schoolcraft’s Manibozho].” Longfellow’s descriptions of Hiawatha were also inspired by Seth Eastman’s depictions of the Dakota in Schoolcraft’s book, as well as by the Mandan and Upper Missouri illustrations made by George Catlin. Longfellow’s, Saint-Gaudens’s, and Shelley’s “creatures” do not fit the fancy of “civilized” society. At one point Shelley’s Frankenstein states, “I heard of the discovery of the American hemisphere, and wept...over the hapless fate of its original inhabitants.”

—James Thomas Stevens (Akwesasne Mohawk)

To trace the arc of the hunched back of this imagined Indian is to follow the call for the end of the wild. Longfellow’s ethnographic errors while naming the nature of this man matter less than repeating a self-fulfilling prophecy in service of a new national tribe, which relies on the neutering of the Indian problem. This body is depicted with sensitive restraint in a state of retreat, requiring the quiver down and weapons appropriately at rest, in order to keep the future settled. This projection helps us come to terms with and justify the foundational violence of wars unfortunately won. Americans, aided by the work of artists, become Native, and Natives are incorporated into the national narrative.

—Jackson Polys (Tlingit)

Philip J. Deloria and Jackson Polys on The Sun Vow

Hermon Atkins MacNeil (American, 1866–1947). The Sun Vow, 1899, cast 1919. Bronze, 72 x 32 1/2 x 54 in. (182.9 x 82.6 x 137.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1919 (19.126)

This sculpture asserts the turn of the twentieth century ethnographic impulse to preserve supposedly disappearing Native cultures from the travails of the modern world. Created in Rome, it embodies a new hybrid aesthetic, its Indian subjects transformed by classical approaches to the human figure. Key to the work is its backstory: the made-up account of a phony Sioux ritual, a tale of generational change replete with grandfatherly advice to “aim high!” That a patently ridiculous story defined the production and reception of this sculpture reveals the ascendant power of modern primitivism. Through art and literature, summer camps and tourist retreats, Americans sought to create an imagined Indian representing an authentic world of nature, community, and spirituality. That fantasy helped sort through the challenges of modernity, even as it erased actual Native peoples.

—Philip J. Deloria (Dakota descent)

How will MacNeil’s story end? The figures are suspended, held captive by a vow that the artist later admitted he perhaps made up. This representation of the futility of Indian action fosters a belief in their aimlessness. Where will the arrow land? It cannot. Ineffective and undirected, it must disappear. This reinforces a limited vision of Native success in which the youth, the next generation, must move beyond the blinded elder. In a celebration of naivety, the child smiles slightly at the release of the powerless arrow, contributing to the acknowledgment of landless future generations—of Natives forcibly separated from their territories, and from themselves. This depiction participates in a ritual of blindness to a civilizing violence understood as necessary.

—Jackson Polys (Tlingit)

Gabriela Spears-Rico and Livia Corona Benjamin on Mexican Girl Dying

Thomas Crawford (American, 1813?–1857). Mexican Girl Dying, by 1846; carved 1848. Marble, 20 1/4 x 54 1/2 x 19 1/2 in. (51.4 x 138.4 x 49.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Annette W. W. Hicks-Lord, 1896 (97.13.2a–e)

The noble maiden is demure, lying in a sexually available position, her nose and chin pointed aimlessly at the sky in a sign of resignation. Her right hand gently cups the bare wound under her breast while her left hand clutches the chain of her cross, a final attempt toward her “salvation.” She dies, forlorn, a casualty of the conquistador lance that pierced her sinews, welcoming the new world, Christianity and “civilization.” But what of her own voyage, of her people’s war to resist foreign occupation? Mexica women, land, imagined as disposable flesh ripe for violation. What did she yearn for in her own wayfaring before the invasion of Cortés? Here, we are all Malinches, frozen in time, being chiseled and gazed at, subject to White men’s exploitation.

—Gabriela Spears-Rico (Pirinda Charense and P’urhépecha)

Silencio. Be quiet.

There is a Mexican

Girl Dying, amongst

the sculptures and decor-

ative objects that

dress the American

Wing. Mantelpieces,

fountains, ornament,

dead centerfold-pose

women. Exposed, cross

in hand, without

citizenship. Where is her

blouse, Mr. Crawford?

Where are the children

with her? Or was

she a child herself?

Across from her sits

a Libyan Sibyl,

aloof, as if to say,

“We demand

museum representation.”

Yet here they are,

pitted against Sèvres

vases, just outside

the café.

A Mexican

girl is dying.

We know why some girls

from Mexico

die and others

do not.

—Livia Corona Benjamin (Mestizo)

Scott Manning Stevens on Fur Traders Descending the Missouri

George Caleb Bingham (American, 1811–1879). Fur Traders Descending the Missouri, 1845. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in. (73.7 x 92.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1933 (33.61)

Famous for its exceptional calm, this work seems more concerned with atmosphere than the narrative vignettes typical of genre painting. The original title, French Trader and Half-Breed Son, provides greater context for Bingham’s masterpiece: French fur traders routinely married Indigenous women to establish the necessary kinship relations that made it possible for them to take furs from Native territories. These marriages not only created valuable trade networks but also established familial obligations of reciprocation that meant goods flowed into Native communities. Bingham’s painting offers an alternative vision of western expansion—one characterized by intermarriage and trade, not conflict. The American Art-Union’s change of title in 1845 from the more racialized and less palatable original resulted in a loss of insight into one facet of the early frontier.

—Scott Manning Stevens (Akwesasne Mohawk)

Bonney Hartley on Hudson River Scene

John Frederick Kensett (American, 1816–1872). Hudson River Scene, 1857. Oil on canvas, 32 x 48 in. (81.3 x 121.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of H. D. Babcock, in memory of his father, S. D. Babcock, 1907 (07.162)

To me, every bend in the Muhheacanituck (Hudson River) is a beloved view. It is a fertile, life-giving place where Mohican ancestors cultivated bountiful harvests and enjoyed tranquil canoe journeys downriver to exchange news, game, and other gifts with their Munsee kin. It is a sacred landscape from which our surviving community continues to derive pride and meaning. It is our namesake, the Muhheacanituck, the waters that are never still. It is home.

The fort’s presence is a reminder of the colonists’ need to defend lands that were not their home. Today that tension is still present even if the forts are not. Every day we confront this truth as we work to protect burial places and other sacred sites. The theft is still unresolved.

—Bonney Hartley (Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican)

Wendy Red Star on Hiawatha and Minnehaha

Left: Hiawatha, 1868. Marble, 13 3/4 x 7 3/4 x 5 1/2 in. (34.9 x 19.7 x 14 cm) (2015.287.1). Right: Minnehaha, 1868. Marble, 11 5/8 x 7 1/4 x 4 7/8 in. (29.5 x 18.4 x 12.4 cm) (2015.287.2). Both: Edmonia Lewis (American, 1844–1907). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup and Friends of the American Wing Funds, 2015

Lewis lived during a period of great change in the United States. While the abolition of slavery and the birth of feminism were positive movements toward equality, the eradication and fictional romanticization of Indigenous peoples were also occurring across the country. Lewis, a woman of West Indian heritage, also claimed Native American lineage. She sought to create her own persona and further her career as a sculptor by purposefully assuming an Indigenous identity. After arriving in Rome in 1865, she created Hiawatha and Minnehaha, figures drawn from the popular literature of colonialist culture, specifically the verse of Longfellow. With successes such as these, Lewis carved a pathway for future generations of female artists of color in a white-male-dominated art world.

—Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke/Crow)

Jami Powell on Indian Vase

Ames Van Wart (American, 1841–1927). Indian Vase, 1876. Marble, 46 1/2 x 24 x 16 in. (118.1 x 61 x 40.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Estate of Marshall O. Roberts, 1897 (97.10)

Created during America’s centennial year and the era of Native American history characterized by forced removal and imposed relocation to reservations, Van Wart’s Indian Vase represents the complexity of American histories and our (mis)understandings of them. This work has long been interpreted as an acknowledgment of the displacement of Native peoples. Here, an assumed dichotomy exists between the figures sitting along the rim: one is defiant, while the other is defeated—though both await their inevitable demise. What happens if we disrupt the lingering nineteenth-century notion that Native peoples are destined to disappear? How would this change our interpretation of these figures?

—Jami Powell (Osage)

Veronica, Rock, and Wolf Pipestem on Hayne Hudjihini, Eagle of Delight

Henry Inman (American, 1801–1846). Hayne Hudjihini, Eagle of Delight, 1832–33. Oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 25 1/4 in. (76.8 x 64.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2018 (2018.501.1)

Born into a prominent Eagle clan family of the Jiwere-Nut'achi (Otoe-Missouria) people, Hayne Hudjihini, Eagle of Delight, has a blue tattoo on her forehead denoting her royal status. Her marriage to Bear clan Chief Sumonyeacathee formed an Eagle-Bear union—a high honor among the Jiwere-Nut'achi people. Following a peace treaty in which the Jiwere-Nut'achi agreed to an alliance with the United States government, in 1822 she and her husband traveled as ambassadors and protectors of Jiwere-Nut'achi sovereignty from their home in present-day Nebraska to Washington, D.C., to meet with President James Monroe. During this trip, Bureau of Indian Affairs superintendent Thomas McKenney is said to have fallen in love with her and commissioned her portrait. Despite Eagle clan members being known for their strength, health, and long lives, she died of measles shortly after she returned home.

—Veronica, Rock, and Wolf Pipestem (Otoe-Missouria), descendants of Hayne Hudjihini

Crystal Echo Hawk on Pes-Ke-Le-Cha-Co

Henry Inman (American, 1801–1846). Pes-Ke-Le-Cha-Co, 1832–33. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gerald and Kathleen Peters, 2018 (2018.501.2)

The history of the Pawnee people is one of great strength, innovation, beauty, and resiliency. Our values—including a respect for family, a shared responsibility for the land, and an obligation to do right by the next generation—have shaped not only who we are today but also American society. This portrait of Pes-Ke-Le-Cha-Co reflects the dignity and strength of the Pawnee people—qualities he exuded when he traveled to Washington, D.C., in 1821–22 to meet with President James Monroe. At the time, settlers were beginning to overrun the Pawnee, bringing disease and violence with them. For centuries, our Pawnee leaders remained strong, and they continue to protect our people today.

—Crystal Echo Hawk (Skee-Haru-Ha-Tawa, Kitkehaki Band, Pawnee)

Kay WalkingStick on The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak

Albert Bierstadt (American, 1830–1902). The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak, 1863. Oil on canvas, 73 1/2 x 120 3/4 in. (186.7 x 306.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.123)

Young and eager to see and draw the western United States, Bierstadt joined Colonel Frederick W. Lander’s 1859 survey expedition to the Nebraska Territory. He separated from Lander’s caravan in the Wind River Range (in present-day Wyoming) to make oil studies of the mountains, animals, and Indigenous people. Painted in New York, the finished work here is a composite based on drawings, photographs, and oil sketches. However, it is not a picture of a specific place, but an idealization of the romance of the American West. The Shoshone village in the foreground bustling with family life represents the old ways, which Bierstadt knew would not last: the bison were being decimated and with them the traditional lifeways of the Indians.

—Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee)

Alan Michelson on Washington Crossing the Delaware

Emanuel Leutze (American, 1816–1868). Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851. Oil on canvas, 12 ft. 5 in. x 21 ft. 3 in. (378.5 x 647.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John Stewart Kennedy, 1897 (97.34)

The boatman pictured in the stern wears Native moccasins, leggings, and a shoulder pouch, and likely represents an Indigenous member of Washington’s troops. Native American warriors fought, often decisively, on both sides of the war—British and American—according to their nation’s interest. In 1778 the United States signed a treaty with the Lenape (Delaware), its first formal treaty with an Indigenous nation, securing assistance and safe passage through Delaware land in exchange for “articles of clothing, utensils, and implements of war.” The treaty recognized Delaware sovereignty, guaranteed territorial rights, and offered the possibility of Indigenous statehood. But soon a (double) crossing of the Delaware took place: persistent treaty violations by settlers and the US government culminated in the 1782 Gnadenhütten Massacre, in which a Pennsylvania militia killed ninety-six defenseless Christian Lenape. Virtually all of America’s Indigenous allies suffered similar fates.

—Alan Michelson (Mohawk)

Jason Lujan on Gallery 765: The West, 1860–1920

Installation view of Gallery 765: The West, 1860–1920

Some kind of sun seems to have set.

An exercise in illustrating the concept of the “terminal narrative,” the works in this gallery occupy the absence of Native North American self-representation during the expansion of the United States in the nineteenth century. Bronze and oil paint; Frederic Remington and Albert Bierstadt; the pre-reservation Indian. While Indigenous figures in works such as these were often modeled after real people, I have found myself wondering if the artists also viewed their subjects as actual human beings.

People often awake from dreams and nightmares and find them unreal, but this has never been the case for me: these powerful and proselytizing images of the West continue to have a profound influence on the inherited realities of contemporary Americans who happen to be born Native.

—Jason Lujan (Chiricahua Apache, Texas)

Margaret Jacobs on The Broncho Buster

Frederic Remington (American, 1861–1909). The Broncho Buster, 1895, revised 1909, cast by November 1910. Bronze, 32 1/4 x 27 1/4 x 15 in. (81.9 x 69.2 x 38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Jacob Ruppert, 1939 (39.65.45)

After regularly seeing casts and reproductions of The Broncho Buster at my first job at the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York, I am now quick to spot them in museums, flea markets, movies, and magazines. The pieces seem to be everywhere, representing the epitome of what many believe a cowboy to be and what Remington hoped he would embody—the last frontiersman and the master of a nation born out of wilderness, subsisting on an unsettled, magical land. I do still wonder—as I did frequently when I was younger—why this artist, who lived so close to the Akwesasne Mohawk Reservation in upstate New York, traveled so far west to find his Native subjects? Maybe too many “Indians” and not enough “Cowboys” would have crushed his mythos of the American West.

—Margaret Jacobs (Akwesasne Mohawk)

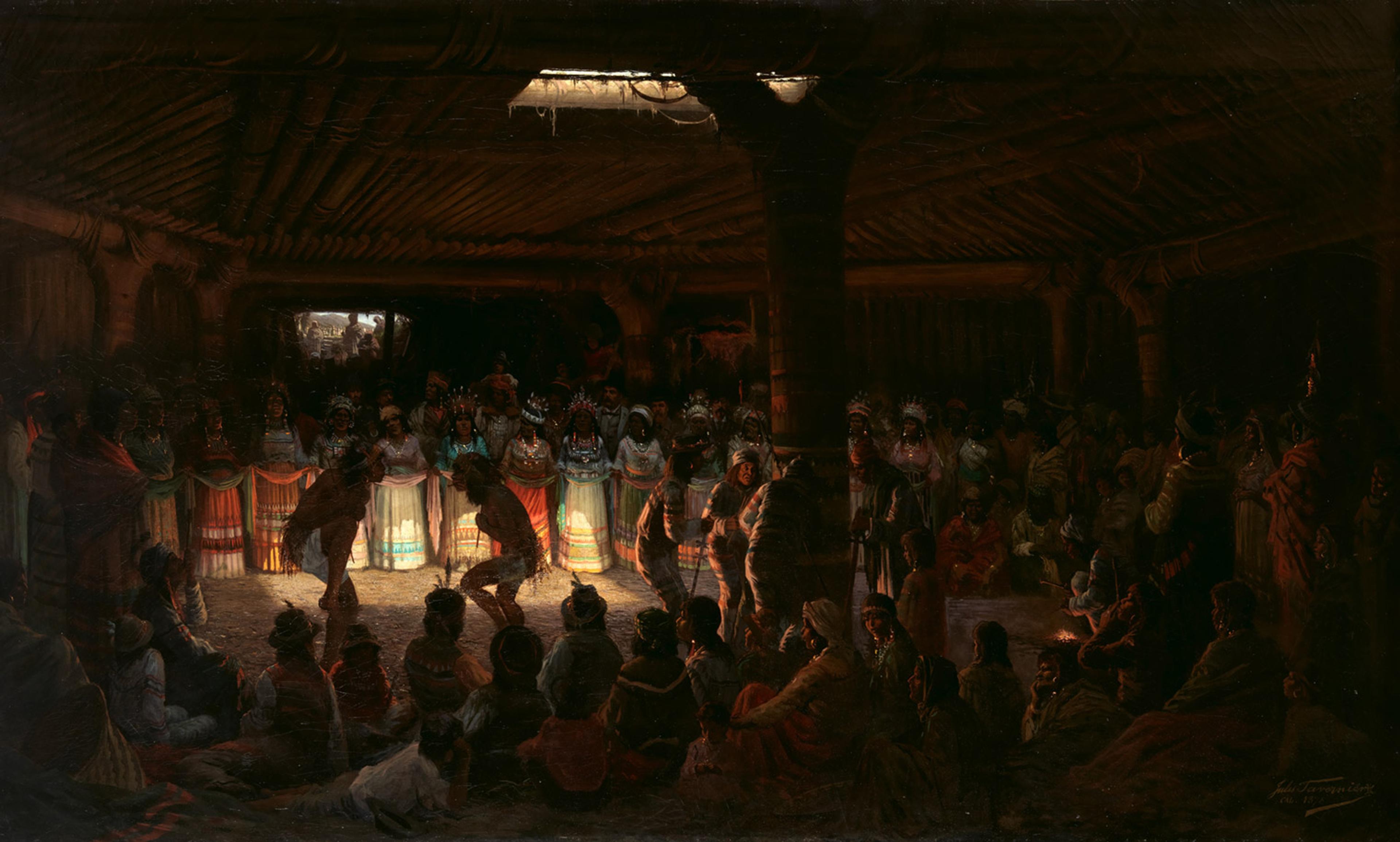

Ty Defoe on Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California

Jules Tavernier (American [born France], 1844–1889). Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California, 1878. Oil on canvas, 48 x 72 1/4 in. (121.9 x 183.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2016 (2016.135)

When the seasons change

we go to the roundhouse.

When it is a birthday

we go to the roundhouse.

When a funeral happens for an elder

we go to the roundhouse.

We unite.

First time I heard the eagle song

It was played in the roundhouse.

It was so powerful my uncle took out his eagle bone whistle

blew it four times in the air as if to call spirits down from the sky,

a circular opening above,

in the night

maps of stars.

Bright.

Clear.

The dust rose from the dancers’ feet.

People in pieces of regalia

jean jackets and shawls draped over shoulders

as if everyone was transforming into animal clans inside a lodge.

Dancers dance to the drum

like a chain for spirits to find their way into our little roundhouse.

Movements are prayers.

Seven years on the earth I was

with ear pressed on the dirt floor.

Now, every time I hear eagle song

I remember the roundhouse.

—Ty Defoe (Ojibwe and Oneida)

Jeffrey Gibson on End of the Trail

James Earle Fraser (American, 1876–1953). End of the Trail, 1918, cast 1918. Bronze, 33 x 26 x 8 3/4 in. (83.8 x 66 x 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund, Mr. and Mrs. S. Parker Gilbert Gift, Morris K. Jesup and 2004 Benefit Funds, 2010 (2010.73)

I remember visiting the Cherokee gift shop as a kid, where small novelty versions of this sculpture were for sale. At the time, I saw it as an image of a shamed, defeated Indian, and I wondered if this was really how the rest of the world viewed us. Over the years, I went to powwows with my family, where I saw End of the Trail screenprinted on flags used in ceremonies honoring veterans and prisoners of war. It was a symbol that had been completely reinvented in a Native context. I continue to have ambivalent feelings about this image, but I understand that for many it is a symbol of resilience and strength—characteristics traditionally associated with the warrior.

—Jeffrey Gibson (Choctaw-Cherokee)

Jeremy Dennis on At the Seaside

William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916). At the Seaside, ca. 1892. Oil on canvas, 20 x 34 in. (50.8 x 86.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967 (67.187.123)

This work depicts a leisurely beach scene painted one year after Chase opened a school of art near the Shinnecock Indian Reservation on Long Island’s East End. This land is situated on the Shinnecock people’s ancestral territory—of which more than 4,422 acres was stolen through an illegal transaction in 1859. The school and Chase’s stay on Long Island were devised by Mrs. Janet S. Hoyt, a wealthy patron of the arts and an artist who lived in the Shinnecock Hills. Hoyt proposed a summer employment opportunity for Chase with the end goal of developing a real-estate venture and transforming the area into a summer-resort destination. Despite the increased eagerness to settle in the Shinnecock Hills, the Shinnecock Indian Nation has remained vigilant in asserting their rightful title to their ancestral land.

—Jeremy Dennis (Shinnecock)

Joe Baker on Delaware Water Gap

George Inness (American, 1825–1894). Delaware Water Gap, 1861. Oil on canvas, 36 x 50 1/4 in. (91.4 x 127.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1932 (32.151)

Painting the air and light of Lenapehoking (the homeland of Lenape peoples) with a deft hand, Inness does little to portray the truth of an American genocide. The Delaware Water Gap, located on the border of Pennsylvania and New Jersey, was the epicenter of colonial mayhem and capitalistic exploitation. By the time this pastoral rendering of peaceful commerce in the rural countryside was completed, my people, the Lenape, had been forcibly removed west to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), Wisconsin, and Canada. The environmental degradation caused by the Industrial Revolution was in full swing seventy miles north along the Hudson River, forever changing the landscape of Lenapehoking. More than a passing storm, capitalism has now threatened our very existence, as we live amid the chaos and destruction of climate change.

—Joe Baker (Delaware Tribe of Indians)

Shawon Kinew on Indian Girl, or The Dawn of Christianity

Erastus Dow Palmer (American, 1817–1904). Indian Girl, or The Dawn of Christianity, 1853–56; carved 1855–56. Marble, 60 x 19 3/4 x 22 1/4 in. (152.4 x 50.2 x 56.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Hamilton Fish, 1894 (94.9.2)

It is difficult to untether this sculpture from the ongoing legacy of colonization, including thousands of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). I am struck by the honesty of the artwork, the careful pairing of sexuality and religion, wherein the body and soul of this nubile neophyte are the desired sites of transformation. My father was a Canadian Indian Residential School survivor, who bore the consequences of this fantasy of flesh and salvation as a very young boy. In the last weeks of my father’s life, in 2012, we witnessed together in Rome the canonization of one of our own—the Haudenosaunee St. Kateri Tekakwitha, who, like the girl depicted here, came across this new religion in our ancient lands. I am left contemplating Dawn and the hope of reconciliation like some foreign body in my palm.

—Shawon Kinew (Ojibways of Onigaming First Nation, pizhiw doodem)

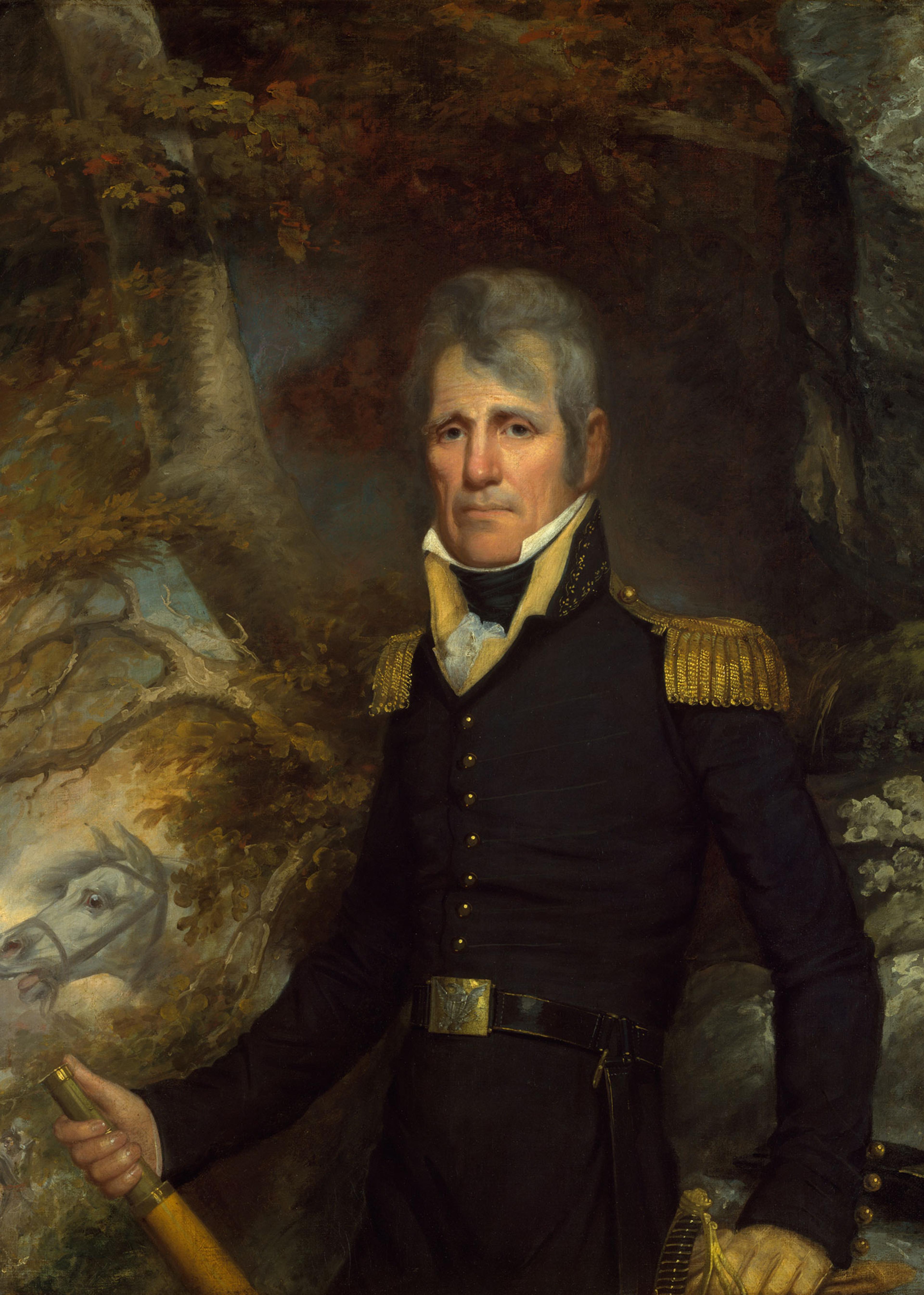

Ned Blackhawk on General Andrew Jackson

John Wesley Jarvis (American [born England], 1780–1840). General Andrew Jackson, ca. 1819. Oil on canvas, 48 1/2 x 36 in. (123.2 x 91.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1964 (64.8)

Few figures in US history have generated as much commemoration, antipathy, and passionate debate as Andrew Jackson. The first president born outside the thirteen colonies, Jackson garnered unprecedented popularity in the early nineteenth century, leading American forces during the War of 1812 as well as in battles against Creek and Seminole communities thereafter.

By 1834 his presidency had become synonymous with an entire Age of Jackson. Few, however, have fully recognized how the rise of Jacksonian Democracy came at the expense of American Indian communities, many of which resisted the president on the battlefield and in the courtroom. Jackson defied the Supreme Court’s 1832 ruling in Worcester v. Georgia, which stipulated that the Cherokee Nation held sovereign authority over Cherokee lands in Georgia. The resulting Trail of Tears remains forever associated with his legacy.

—Ned Blackhawk (Western Shoshone)

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle on Marinus Willett

Ralph Earl (American, 1751–1801). Marinus Willett, ca. 1791. Oil on canvas, 91 1/4 x 56 in. (231.8 x 142.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Willett Van Nest, 1916 (17.87.1)

His gaze limited by colonial blinkers, Ralph Earl did not adequately depict my two Muscogee companions or properly render my likeness as a time-traveling, shape-shifting, gender-fluid supernatural being whose radiance knows no equal. Instead, he placed in the foreground Marinus Willett, who participated in an attack in which a dozen Onondaga villages were burned to the ground, and who fought the Mohawks of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy before declaring himself advocate for the Creeks and compelling them to sign the 1790 Treaty of New York—one of five hundred treaties that would soon be broken by the US government. For these manipulations, Willett was gifted this fine Parisian sword, whose many layers of meaning, dear viewer, I shall leave to you to interpret.

—Miss Chief Eagle Testickle (alter ego of Kent Monkman, Cree)