Cassone with painted front panel depicting the Conquest of Trebizond

Attributed to workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso Italian

and workshop of Marco del Buono Giamberti Italian

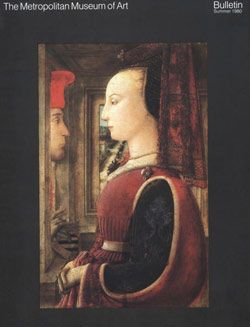

Purchased in 1913 from the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini (1836–1922), this elaborate chest, or cassone, has long enjoyed status as one of the few fifteenth-century objects of its kind to survive intact and, moreover, to portray a contemporary historical event—the conquest of Trebizond, the last outpost of the Byzantine Empire, by Mehmed II in 1461 (for another example of a cassone panel depicting a contemporary historical event, see 07.120.1). This status has been called into question by a detailed, technical examination undertaken in 2008. It has now been demonstrated that so far from being intact, various parts of the chest are not integral and that, most importantly, the painted front may originate from another chest. This means that the purported provenance of the chest from Palazzo Strozzi, first asserted by Weisbach [see Ref. 1913], may have no bearing on the interpretation of the scene on the painted front. That the chest itself is connected with some member of the Strozzi family is clear from the emblems that appear on the end pieces, which are original to it: the Strozzi falcon or hawk perched on a caltrop (spiky metal devices that, when scattered on the ground, destabilize the enemy’s horses) with a banderole inscribed ME[Z]ZE—perhaps indicating another Strozzi emblem, the half-moon crescent [see Ref. Nickel 1974]. The inside of the lid and the back of the cassone retain their original stenciled patterns simulating patterned fabric, and the top of the lid is embellished by a gessoed piece of cloth that is gilded and tooled to simulate a runner of cut velvet (this motif is worn, the paint having been almost entirely lost, so that the design is barely legible today).

The scene on the painted front is universally recognized as coming from the most active and prestigious workshop for the production of painted cassone in mid-fifteenth-century Florence: that shared by Apollonio di Giovanni and Marco del Buono. Its subject is neither biblical nor mythological, nor even based on a contemporary novella such as those by Boccaccio. Rather, it depicts an event that unfolds before two identifiable cities of the Byzantine Empire. Much work has been done identifying the places shown [see especially Refs. Paribeni 2001, Paribeni 2002, and Lurati 2005]. In the left background, clearly labeled on its walls, is Constantinople. An attempt has been made by the artist to suggest a number of the city’s landmarks and distinguishing topographical features, some of which are also labeled. There is the Latin church of San Francesco; the monumental column of Justinian in the Augustaion and the Egyptian obelisk (evidently topped by a crescent) in the Hippodrome originally laid out by Emperor Septimus Severus in the third century AD and further embellished by Constantine; the Hagia Sofia; the nearby sixth-century church of Saint Irene; what must be intended either as the Blachernae Palace or its thirteenth-century annex, the Palace of Porphyrogenitus, which served as the imperial residence for the last Byzantine emperors (the fragmentary inscription may possibly have been intended as [PALAZZO] DEILO [IM]PER[AT]ORI); the Golden Horn—the city’s fabled inlet that was protected by a chain that could be drawn across it—with western ships (carracks) moored next to the Genoese quarter of Pera, the walls of which are dominated by the great circular Galata tower, atop which the Genoese flag can be seen. Other boats in the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara may be either Greek dromons or Ottoman. Further back, on the European side of the Bosphorus, is the CHASTEL NVOVO (the "new fortress" of Rumeli Hisari built by Mehmed II in 1451–52 in preparation for the seige of Constantinople; its distinctive towers are still a landmark today). Across the Bosphorus is another walled city designated as LO SCUTARIO—Scutari, present-day Üsküdar (the name, Skutarion, derived from the leather shields of the Roman soldiers stationed there; it fell to the Ottomans almost a century before Constantinople). Then, dominating the hill on the right is the walled city of Trebizond (modern-day Trabzon). Located on the southern coast of the Black Sea, it became the seat of a separate Byzantine empire when it was conquered by Alexios Komenos in 1204—the year Constantinople fell to the crusaders—and was the last outpost of the Byzantine Empire following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453. It fell to the Ottomans in 1461, marking the final demise of Byzantium. Although hardly an accurate depiction, it seems clear that for his depiction of Constantinople the artist was supplied with descriptions and maps, such as the one included in Cristoforo Buondelmonti’s Liber insularum Archipelagi of 1420 [see Ref. Pope-Hennessy and Christiansen 1980] as well as, possibly, drawings by that inveterate traveler Cyriac of Ancona and the reports of other visitors to the city [see Ref. Lurati 2005].

Before the walled city of Trebizond is depicted a battle. An encampment of tents is shown on the far right, in front of which the leader of one of the armies is seated on a triumphal chariot drawn by two white horses. He wears a turban, as do other members of his army, including the troops emerging behind Scutari, and he points his white baton towards a gesticulating, bearded figure who, dressed in blue, wears the sort of cylindrical hat splayed out at the top that was associated in Western Europe with the Byzantine Greeks [see Ref. Lurati 2005]; he rides a black steed and is plainly either reporting on the progress of the battle or taking orders. Prior to 1980 it was presumed that the figure on the chariot was Mehmed II [see Ref. Weisbach 1913] and that the battle depicted the Ottoman defeat of the Byzantines in 1461—hence the designation of the chest as the Trebizond Cassone. However, as has been pointed out by Paribeni [see Ref. 2001], Trebizond was taken by Mehmed II without a battle: it capitulated without bloodshed. Moreover, a close examination of the costumes reveals that it is the Ottomans who are being vanquished (for the costumes, see especially Refs. Paribeni 2001, Paribeni 2002, and Lurati 2005). Clearly shown among the captives and those in retreat are members of the Ottoman elite infantry, the Janissaries, wearing their distinctive white conical hats with the top folded over. Other conical hats are gold, some with a feathered decoration (for similar Turkish costumes, see Cesare Vecellio’s Degli habiti antichi . . . , Venice, 1664, book 7, pp. 297–302). Their commander is almost certainly the turbaned figure to the left of the melee, dressed in gold, holding a scepter and mounted on a black horse. He is defended by Janissaries, one of whom turns around while pointing with his left hand. Scimitars are wielded by both armies, as are the distinctive recurved composite bows of Ottoman warfare. In front of the triumphal chariot five captives, two of whom kneel, are being presented to the victorious army commanders. The characterization of the two armies should have been enough to refute the common identification of the figure on the triumphal chariot as Mehmed II. And, in fact, a careful examination with the aid of infrared light in 1980 revealed an inscription identifying him as TAN[B]VRLANA—Tamerlane, or Timur (1336–1405), the celebrated Mongol emperor and commander who defeated the Ottomans under Bayezid I at Ankara in 1402 (Bayezid was taken prisoner). The battle, then, would seem to be Tamerlane’s victory over Bayezid at Ankara, but anachronistically shown against the backdrop of Trebizond. As remarked by Gombrich [see Ref. 1955], "it cannot have been the intention of the painter simply to represent a Greek disaster." And, indeed, the setting of a battle that took place in 1402 in front of a city that fell to the Ottomans in 1461 signals an emblematic intent.

In the minds of Europeans, Tamerlane’s victories assured him a place among the "worthies". As such, his image was included in a fresco cycle of famous men commissioned about 1432 by Cardinal Giordano Orsini for his palace in Rome. A number of interpretations have been suggested to explain the apparent anachronisms (see the thorough summary in Ref. Krohn 2008). One would have it that the figure is not actually Tamerlane but the Turkmen rival of the Ottomans, Uzun Hasan (1423–1478), who was known in his time as a second Tamerlane [see Ref. Paribeni 2001 and Baskins, as reported in Ref. Krohn 2008]. Uzun Hasan made a pact with Mehmed II not to aid the Byzantine forces and thus to assist the Ottoman conquest of Trebizond. How this relates to the actual battle scene depicted remains problematic, but it may be worth noting that the Venetians sought Uzun Hasan as an ally against the Ottomans. What cannot be doubted is the intention to conflate historical events, using the past as a template for the future by reminding viewers that the Ottomans—now a threat to Europe—were not invincible. Paribeni [see Ref. 2001] has indicated a pair of cassoni panels commissioned from the workshop of Apollonio, apparently in 1461, that illustrate the triumph of the Greeks over Xerxes’ invading Persian army in 480–79 BC. Given the date of the commission, there would appear to be a reference to the conquest of Trebizond, the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, and a hoped for reversal. At the Council of Mantua in 1459, Pius II promoted a crusade against the Turks. An army was assembled in Ancona in 1464, but dispersed when Pius died there on August 15. There were, of course, also mercantile interests, and Paribeni [see Ref. 2001] has pointed out that in December 1460 an accord established a Florentine commercial presence in Trebizond. The presence on the MMA cassone of the two cities of Constantinople and Trebizond would thus seem to transform Tamerlane’s victory at Ankara in 1402 into an emblematic prognosis for the defeat of the Ottoman conquerors of Trebizond.

As noted above, the painted front may have belonged to another chest so that the attempts to link it with the Strozzi remain speculative. Moreover, it has not been proven that the chest itself came from the Strozzi palace, though it contains Strozzi emblems. Several Strozzi marriages have been suggested as appropriate moments for the commission: Caterina Strozzi, who married Jacopo degli Spini in 1462 [see Ref. Nickel 1974]; the brother of Vanni di Francesco Strozzi, who traveled to Constantinople and Trebizond in 1462 and who commissioned a cassone from Apollonio for the marriage [see Ref. Paribeni 2001]; Strozza di Messer Marcello degli Strozzi, who married in 1459; Benedetto di Marco degli Strozzi, who married in 1462 [Baskins, reported in Ref. Krohn 2008]; and finally, most prominent of all, the wealthy banker Filippo Strozzi—the builder of Palazzo Strozzi—who married Fiammetta degli Adimari in 1466 [Beatrice Paolozzi-Strozzi, in Ref. Krohn 2008].

#5059. Painted front panel depicting the Conquest of Trebizond, Part 1

-

5059. Painted front panel depicting the Conquest of Trebizond, Part 1

-

5060. Painted front panel depicting the Conquest of Trebizond, Part 2

Playlist

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.