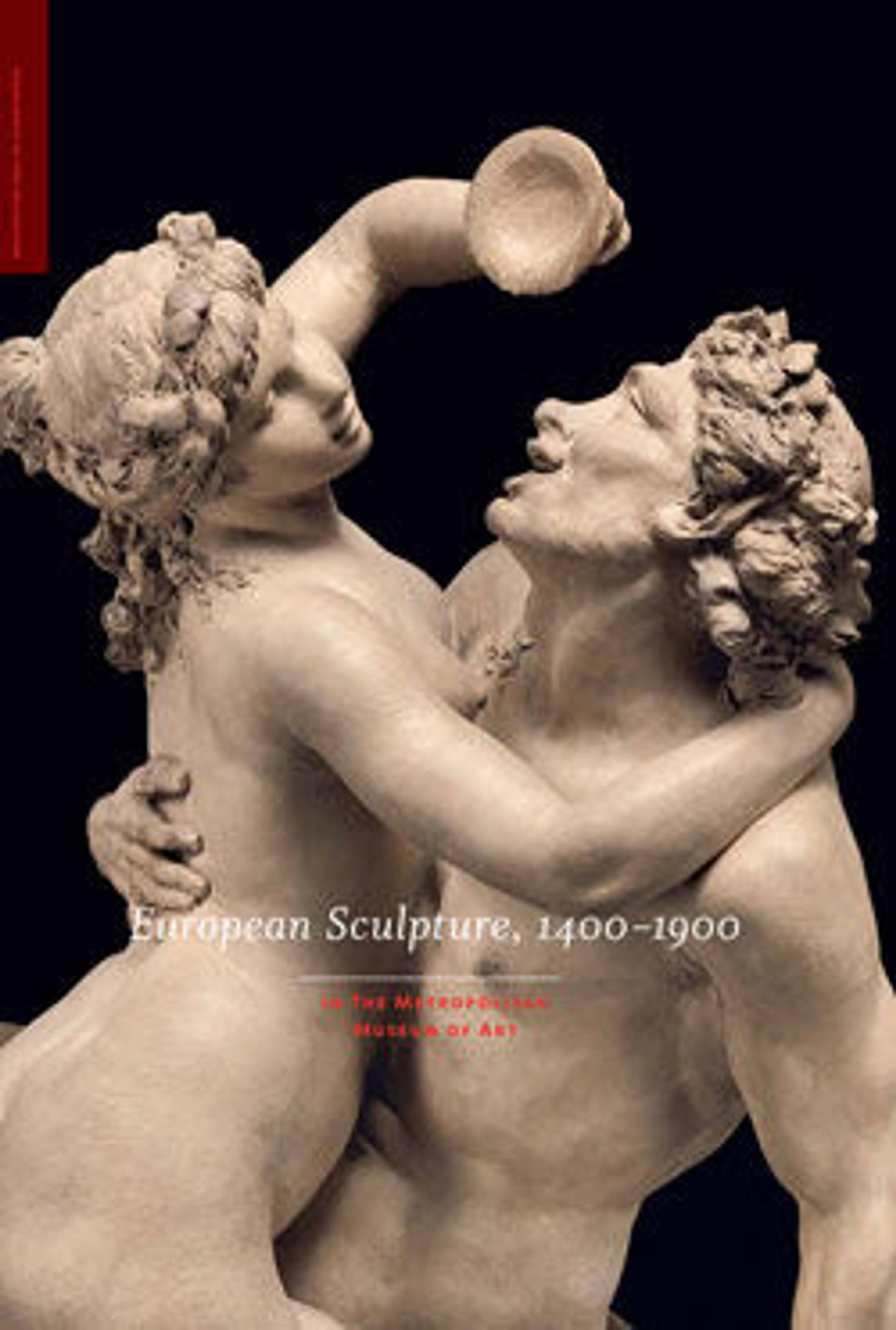

Tarquin and Lucretia

In the late sixteenth century the innovative style and phenomenal success of the sculptor Giambologna (see entry no. 30) attracted many artists to Florence to join his large workshop. Two sculptors born, as was that master, in the Low Countries — Hubert Gerhard, from s’ Hertogenbosch, and Adriaen de Vries, from The Hague — absorbed his manner but transformed it into distinctive idioms that they carried back to northern Europe. De Vries (see entry no. 32) was peripatetic, occupied by commissions in Milan, Turin, Augsburg, and Prague; Gerhard worked mainly in the South German cities of Augsburg, Innsbruck, and Munich. Both mastered the medium of bronze, working often at a large or lifesize scale but also producing statuettes. This Tarquinius and Lucretia, of which a number of versions exist, intersects with aspects of each sculptor’s style, and over the years its attribution has shifted back and forth between them.1

In the Museum’s bronze group the struggling figures’ tightly interwoven limbs express the tension and violence of the historical subject, the rape of a Roman matron, which prompted her suicide (see entry no. 50). Hubert Gerhard’s large-scale sculpture Mars, Venus, and Cupid (ca. 1585 – 90, Schloss Kirchheim, near Augsburg), and a smaller, variant bronze of the subject he produced some two decades later (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) are closely related to the present work in their composition, especially in the way the man’s leg is slung over the woman’s.2 On this basis, the scholarly world concurred that Gerhard must have devised the Tarquinius and Lucretia. Recent reappraisals not only of Gerhard’s work but also of De Vries’s have put the authorship of this bronze group at issue. In 1998 Frits Scholten found the movement of the figures coordinated in one direction to be unlike the complex, back-and-forth poses of Gerhard’s groups, particularly the Mars, Venus, and Cupid. 3 He also singled out two De Vries compositions, the Gladiator (ca. 1602 – 11, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) and the lost statue of Cleopatra, known through prints, as sources for the two figures. In 2000 the foremost expert on Gerhard, Dorothea Diemer, thought that the Tarquinius and Lucretia could be by either Gerhard or De Vries, but in her latest publication, which is the definitive study of Gerhard to date, she relegates it to a "rejected attributions" category.4 Yet the movements of Tarquinius and Lucretia seem more tightly structured than De Vries’s loose-limbed, off-kilter poses and generally more in line with Gerhard’s disciplined compositions; thus, we maintain the attribution to Gerhard here, while acknowledging Diemer’s opinion to the contrary.

Unusual for either artist is the large number of casts that exist of this group. At least ten are known, including one of lesser quality in the Jack and Belle Linsky collection in this Museum.5 Significant differences distinguish them. For example, in the present version, there is no drapery over or under Tarquinius’s slung leg but some falls over Lucretia’s left leg; a version in Cleveland shows cloth draped over the left thighs of both protagonists; and in yet another version, in a private collection in England, Lucretia has no drapery over her left thigh but a passage of fabric separates her thighs from his.6 In each work cloth threads through the limbs in different rhythms; for this author, the direct contact of flesh on flesh in the Museum’s version offers the most forceful representation of sexual predation. William Wixom has argued that the Cleveland version was the first one because it lacks a base and has the subtlest modeling. Scholten, on the other hand, believed that either the version in an English collection or the one in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, is likely to be the original because of their square bases (a preference of De Vries’s) and because the figures lack a cache-sexe. There is a considerable range in the quality of the casting among the ten versions, and some have faults in their metal; this and the substantial differences among the models make it likely that the ten were produced over a significant period of time, probably with the intervention of other artists. The Museum’s work was only minimally chased after casting; it has a skillful join below the elbow of Tarquinius’s right arm and a repair of screwed-in plugs below Lucretia’s left knee.

1. Diemer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 178 – 79 , no. t-l2, summarizes the changes of attribution, and vol. 1, pp. 405 – 11, offers an extensive account of the factors weighed in making these attributions.

2. For the Mars, Venus, and Cupid at Schloss Kirchheim, see ibid., vol. 1, fig. 154, vol. 2, pp. 147 – 49, no. g7, pls. 21 – 25, 128b – 31, and for the variant at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, ibid., vol. 2, no. g16, pp. 158 – 59, pls. 3, 72, 73.

3. Scholten 1998b; Frits Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36.

4. Diemer in De Vries 2000, pp. 331 – 33, no. 45; Diemer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 178 – 79, no. t-l2.

5. William D. Wixom in Renaissance Bronzes 1975, n.p., no. 213, provides a list of the variants, to which should be added the version in an English private collection (Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36, no. 11). The version in the Linsky collection is acc. no. 1982.60.122.

6. For the Cleveland version, see Wixom in Renaissance Bronzes 1975, n.p., no. 213, and for the version in a private collection, see Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36, no. 11.

In the Museum’s bronze group the struggling figures’ tightly interwoven limbs express the tension and violence of the historical subject, the rape of a Roman matron, which prompted her suicide (see entry no. 50). Hubert Gerhard’s large-scale sculpture Mars, Venus, and Cupid (ca. 1585 – 90, Schloss Kirchheim, near Augsburg), and a smaller, variant bronze of the subject he produced some two decades later (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) are closely related to the present work in their composition, especially in the way the man’s leg is slung over the woman’s.2 On this basis, the scholarly world concurred that Gerhard must have devised the Tarquinius and Lucretia. Recent reappraisals not only of Gerhard’s work but also of De Vries’s have put the authorship of this bronze group at issue. In 1998 Frits Scholten found the movement of the figures coordinated in one direction to be unlike the complex, back-and-forth poses of Gerhard’s groups, particularly the Mars, Venus, and Cupid. 3 He also singled out two De Vries compositions, the Gladiator (ca. 1602 – 11, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) and the lost statue of Cleopatra, known through prints, as sources for the two figures. In 2000 the foremost expert on Gerhard, Dorothea Diemer, thought that the Tarquinius and Lucretia could be by either Gerhard or De Vries, but in her latest publication, which is the definitive study of Gerhard to date, she relegates it to a "rejected attributions" category.4 Yet the movements of Tarquinius and Lucretia seem more tightly structured than De Vries’s loose-limbed, off-kilter poses and generally more in line with Gerhard’s disciplined compositions; thus, we maintain the attribution to Gerhard here, while acknowledging Diemer’s opinion to the contrary.

Unusual for either artist is the large number of casts that exist of this group. At least ten are known, including one of lesser quality in the Jack and Belle Linsky collection in this Museum.5 Significant differences distinguish them. For example, in the present version, there is no drapery over or under Tarquinius’s slung leg but some falls over Lucretia’s left leg; a version in Cleveland shows cloth draped over the left thighs of both protagonists; and in yet another version, in a private collection in England, Lucretia has no drapery over her left thigh but a passage of fabric separates her thighs from his.6 In each work cloth threads through the limbs in different rhythms; for this author, the direct contact of flesh on flesh in the Museum’s version offers the most forceful representation of sexual predation. William Wixom has argued that the Cleveland version was the first one because it lacks a base and has the subtlest modeling. Scholten, on the other hand, believed that either the version in an English collection or the one in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, is likely to be the original because of their square bases (a preference of De Vries’s) and because the figures lack a cache-sexe. There is a considerable range in the quality of the casting among the ten versions, and some have faults in their metal; this and the substantial differences among the models make it likely that the ten were produced over a significant period of time, probably with the intervention of other artists. The Museum’s work was only minimally chased after casting; it has a skillful join below the elbow of Tarquinius’s right arm and a repair of screwed-in plugs below Lucretia’s left knee.

1. Diemer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 178 – 79 , no. t-l2, summarizes the changes of attribution, and vol. 1, pp. 405 – 11, offers an extensive account of the factors weighed in making these attributions.

2. For the Mars, Venus, and Cupid at Schloss Kirchheim, see ibid., vol. 1, fig. 154, vol. 2, pp. 147 – 49, no. g7, pls. 21 – 25, 128b – 31, and for the variant at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, ibid., vol. 2, no. g16, pp. 158 – 59, pls. 3, 72, 73.

3. Scholten 1998b; Frits Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36.

4. Diemer in De Vries 2000, pp. 331 – 33, no. 45; Diemer 2004, vol. 2, pp. 178 – 79, no. t-l2.

5. William D. Wixom in Renaissance Bronzes 1975, n.p., no. 213, provides a list of the variants, to which should be added the version in an English private collection (Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36, no. 11). The version in the Linsky collection is acc. no. 1982.60.122.

6. For the Cleveland version, see Wixom in Renaissance Bronzes 1975, n.p., no. 213, and for the version in a private collection, see Scholten in De Vries 1998, pp. 134 – 36, no. 11.

Artwork Details

- Title: Tarquin and Lucretia

- Artist: After a model attributed to Hubert Gerhard (Netherlandish, 1540/50–1621, active Germany)

- Date: 1605–10

- Culture: German

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): H. 19 13/16 x W. 15 x D. 15 3/8 in. (50.3 x 38.1 x 39.1 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1950

- Object Number: 50.201

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.