Cherub and shell

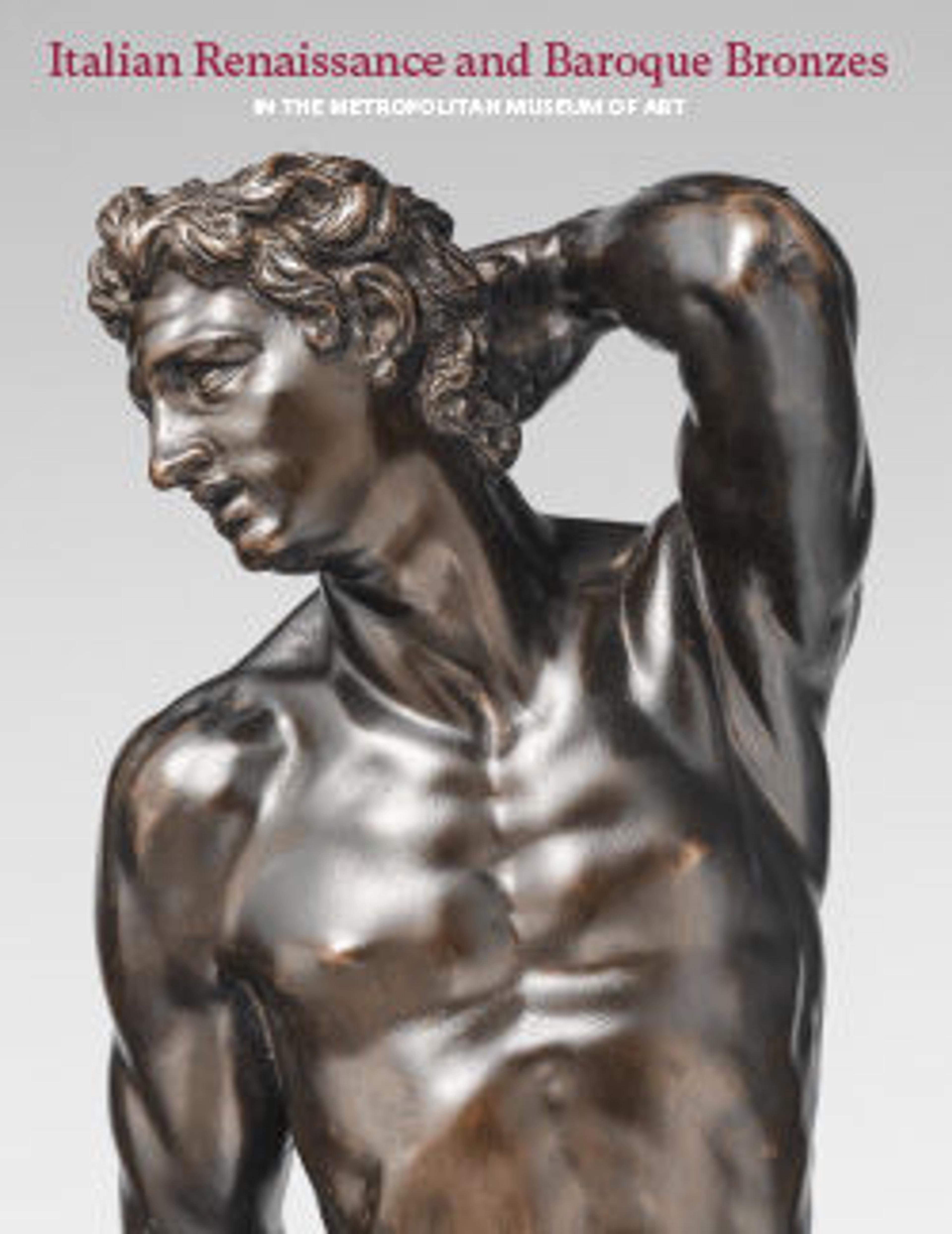

In the Catholic tradition, four-winged cherubim belong to the second order of the hierarchy of angels and attend close to God in heaven. In this remarkable bronze, a single cherub is crowned with a fillet dotted with flowers. The tops of two arched wings flank its head; another pair gently enfolds beneath its chin. A large scallop-shaped shell fans outward below the wings like an expanding burst of radiance. With lowered head and wide-open eyes, the cherub looks downward, revealing its teeth in a broad smile. Its transfixed expression conveys the encompassing, beatific joy of beings who dwell in God’s presence as witnesses to divine glory. The shell is a symbol of baptism and pilgrimage that in its metaphorical sense alludes to the journey of the soul upward toward God.

In 1986, James David Draper, the last to publish this bronze, described its facture and probable architectural function: “the head of this spiritello is separately cast, attached to the wings and shell by an original pin at the throat and modern screws behind the ears. The projection[s] for support in the back [at the top and bottom, fig. 3a], the size of the object as a whole, and the cherub’s inclined head, indicate an architectural purpose, probably high on a column or pilaster, forming part of the capital of a tomb or altar.” Draper assigned the bronze to an unknown artist cognizant of the style of the Florentine master Donatello, dated the work to the mid-fifteenth century, and in a cautionary aside stated, “The hardy manufacture and pleasing red brown natural patina notwithstanding, the present work can only be considered generically Donatellesque until its relevant context is found.”[1]

W. R. Valentiner first attributed the Cherub and Shell to the “workshop of Donatello” in 1938, and to this day the bronze has hovered in the orbit of the master. Firstly, the cherub aligns with Donatello’s stylistic vocabulary. Many scholars have noted the formal similarities between it and Donatello’s smiling terracotta putti surmounting the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, Florence, as well as the kinship between the cherub’s physiognomy and that of Donatello’s bronze Amor-Atys (Bargello).[2] The facial features of the large-scale kneeling bronze Putti in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, as well as those of the two wood Spiritelli in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and an American private collection are also similar to the cherub’s.[3] Secondly, the combination of the cherub head and shell is reminiscent of Donatello’s inventive and characteristically eclectic approach to deploying antique motifs that, although often unclassical, is never without meaning. This exact juxtaposition, however, does not appear in Donatello’s oeuvre or, as far as is known, any other fifteenth-century sculpture or painting. In architectural decoration, cherubim and shells are shown proximate to each other but are not combined. For example, in the Old Sacristy in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and executed between 1421 and 1440, a series of winged cherubim decorate the string-course beneath the cornice that symbolically separates the earthly realm of the sacristy below from the large domed heavenly space above. The squinches supporting the small dome over the sacristy’s altar are embellished with scallop shells symbolizing the soul’s ascent. These sculptural and architectural elements are conflated in our bronze—the design of the scallop shell, for example, is a combination of fluting and reverse lozenges generally seen on columns and capitals. The artist responsible for the Cherub and Shell appears to have condensed the language of architectural ornament given over to ecclesiastical spaces into a single sculptural symbol that powerfully signals the celestial realm.

Although the Cherub and Shell evokes Donatello’s style and use of motifs, it does so from a distance. The modeling of the forms is hard, and details—the feathers on the cherub’s wings, the concave fluted elements on the shell—are rendered and tooled in an aggressively precise, linear manner that is unlike works by the master. Donatello was above all a modeler, and as Draper perceptively noted, “the working of some details, such as the engraved wavelets for eyebrows, asserts traditions of metalworking more than those of sculpture considered in its freest plastic sense.”[4] As the sole example of its kind known, The Met bronze remains a work in search of a context, architectural or otherwise. There is, however, good reason for dating it at the earliest to the 1470s—the period following the master’s death when his experimental style had permeated workshops throughout Italy.

Four marble pedestals recently attributed to Gregorio di Lorenzo, a student of Desiderio da Settignano, date to this time (fig. 3b). They are embellished with the same symbolically meaningful combination of four-winged cherubim and shells as our bronze, and the facial features of some of the cherub heads decorating the corners of the pedestals are formally similar to it. Thought to have served as bases for candelabra, the pedestals also have been associated with an uncompleted design for the tomb of Cosimo I in San Lorenzo, Florence.[5]

Like many sculptors of the generation following Donatello, and indeed like the master himself, Gregorio was peripatetic. In the early 1470s in Perugia, his path intersected with that of Mino da Fiesole, who ran concurrent workshops in Florence and Rome, and Urbano da Cortona, a sculptor who, as a member of Donatello’s shop in the 1440s, was responsible for one of the angel reliefs for the bronze high altar of Saint Anthony in Padua.[6] On the marble frame of Mino’s Baglione altar in the Vibi Chapel in San Pietro, Perugia (1473), is found the peculiar separation between the cherub’s head and wings that is intrinsic to the design of The Met bronze. The facial features of the standing putti on Urbano’s marble tomb of Giovanni Andrea Baglione on the retro-facade of Perugia Cathedral are generically similar in style to our cherub. Although the specific architectural context and purpose of the Cherub and Shell might forever remain unknown, the approximate date and formal characteristics of the work seem to sit within the context of sculptures created by lesser-known artists who drew from and transformed Donatello’s style as they carried out their commissions across Italy.

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Detroit 1985, p. 130. I should like to thank Shelley Zuraw for her contributions to this entry.

2. See Caglioti 2005.

3. For the Putti, see Caglioti 2001; for the Spiritelli, see Caglioti et al. 2015.

4. Detroit 1985, p. 130.

5. For the pedestals and the career of Gregorio di Lorenzo, see Bellandi 2010, no. III.8.16; Barocchi 1985, pp. 286–97.

6. See Marco Pizzo in Padua 2001, pp. 56, 58–59.

7. Ragghianti Collobi 1949, p. 46, cat. 8.

8. Joseph Brummer’s inventory records this object as a “15th century bronze representing head of a child on a shell.” Cloisters Archives, Brummer Gallery Records, no. P5598.

In 1986, James David Draper, the last to publish this bronze, described its facture and probable architectural function: “the head of this spiritello is separately cast, attached to the wings and shell by an original pin at the throat and modern screws behind the ears. The projection[s] for support in the back [at the top and bottom, fig. 3a], the size of the object as a whole, and the cherub’s inclined head, indicate an architectural purpose, probably high on a column or pilaster, forming part of the capital of a tomb or altar.” Draper assigned the bronze to an unknown artist cognizant of the style of the Florentine master Donatello, dated the work to the mid-fifteenth century, and in a cautionary aside stated, “The hardy manufacture and pleasing red brown natural patina notwithstanding, the present work can only be considered generically Donatellesque until its relevant context is found.”[1]

W. R. Valentiner first attributed the Cherub and Shell to the “workshop of Donatello” in 1938, and to this day the bronze has hovered in the orbit of the master. Firstly, the cherub aligns with Donatello’s stylistic vocabulary. Many scholars have noted the formal similarities between it and Donatello’s smiling terracotta putti surmounting the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, Florence, as well as the kinship between the cherub’s physiognomy and that of Donatello’s bronze Amor-Atys (Bargello).[2] The facial features of the large-scale kneeling bronze Putti in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, as well as those of the two wood Spiritelli in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and an American private collection are also similar to the cherub’s.[3] Secondly, the combination of the cherub head and shell is reminiscent of Donatello’s inventive and characteristically eclectic approach to deploying antique motifs that, although often unclassical, is never without meaning. This exact juxtaposition, however, does not appear in Donatello’s oeuvre or, as far as is known, any other fifteenth-century sculpture or painting. In architectural decoration, cherubim and shells are shown proximate to each other but are not combined. For example, in the Old Sacristy in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and executed between 1421 and 1440, a series of winged cherubim decorate the string-course beneath the cornice that symbolically separates the earthly realm of the sacristy below from the large domed heavenly space above. The squinches supporting the small dome over the sacristy’s altar are embellished with scallop shells symbolizing the soul’s ascent. These sculptural and architectural elements are conflated in our bronze—the design of the scallop shell, for example, is a combination of fluting and reverse lozenges generally seen on columns and capitals. The artist responsible for the Cherub and Shell appears to have condensed the language of architectural ornament given over to ecclesiastical spaces into a single sculptural symbol that powerfully signals the celestial realm.

Although the Cherub and Shell evokes Donatello’s style and use of motifs, it does so from a distance. The modeling of the forms is hard, and details—the feathers on the cherub’s wings, the concave fluted elements on the shell—are rendered and tooled in an aggressively precise, linear manner that is unlike works by the master. Donatello was above all a modeler, and as Draper perceptively noted, “the working of some details, such as the engraved wavelets for eyebrows, asserts traditions of metalworking more than those of sculpture considered in its freest plastic sense.”[4] As the sole example of its kind known, The Met bronze remains a work in search of a context, architectural or otherwise. There is, however, good reason for dating it at the earliest to the 1470s—the period following the master’s death when his experimental style had permeated workshops throughout Italy.

Four marble pedestals recently attributed to Gregorio di Lorenzo, a student of Desiderio da Settignano, date to this time (fig. 3b). They are embellished with the same symbolically meaningful combination of four-winged cherubim and shells as our bronze, and the facial features of some of the cherub heads decorating the corners of the pedestals are formally similar to it. Thought to have served as bases for candelabra, the pedestals also have been associated with an uncompleted design for the tomb of Cosimo I in San Lorenzo, Florence.[5]

Like many sculptors of the generation following Donatello, and indeed like the master himself, Gregorio was peripatetic. In the early 1470s in Perugia, his path intersected with that of Mino da Fiesole, who ran concurrent workshops in Florence and Rome, and Urbano da Cortona, a sculptor who, as a member of Donatello’s shop in the 1440s, was responsible for one of the angel reliefs for the bronze high altar of Saint Anthony in Padua.[6] On the marble frame of Mino’s Baglione altar in the Vibi Chapel in San Pietro, Perugia (1473), is found the peculiar separation between the cherub’s head and wings that is intrinsic to the design of The Met bronze. The facial features of the standing putti on Urbano’s marble tomb of Giovanni Andrea Baglione on the retro-facade of Perugia Cathedral are generically similar in style to our cherub. Although the specific architectural context and purpose of the Cherub and Shell might forever remain unknown, the approximate date and formal characteristics of the work seem to sit within the context of sculptures created by lesser-known artists who drew from and transformed Donatello’s style as they carried out their commissions across Italy.

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Detroit 1985, p. 130. I should like to thank Shelley Zuraw for her contributions to this entry.

2. See Caglioti 2005.

3. For the Putti, see Caglioti 2001; for the Spiritelli, see Caglioti et al. 2015.

4. Detroit 1985, p. 130.

5. For the pedestals and the career of Gregorio di Lorenzo, see Bellandi 2010, no. III.8.16; Barocchi 1985, pp. 286–97.

6. See Marco Pizzo in Padua 2001, pp. 56, 58–59.

7. Ragghianti Collobi 1949, p. 46, cat. 8.

8. Joseph Brummer’s inventory records this object as a “15th century bronze representing head of a child on a shell.” Cloisters Archives, Brummer Gallery Records, no. P5598.

Artwork Details

- Title: Cherub and shell

- Artist: Sculptor close to Donatello (Italian)

- Date: possibly 1470s

- Culture: Italian, Florence

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (wt. confirmed): 15 1/2 x 17 1/2 in., 31lb. (39.4 x 44.5 cm, 14.0615kg) [Weight shell: 11.75 kg; Weight head: 1.75 kg]

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1958

- Object Number: 58.115

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.