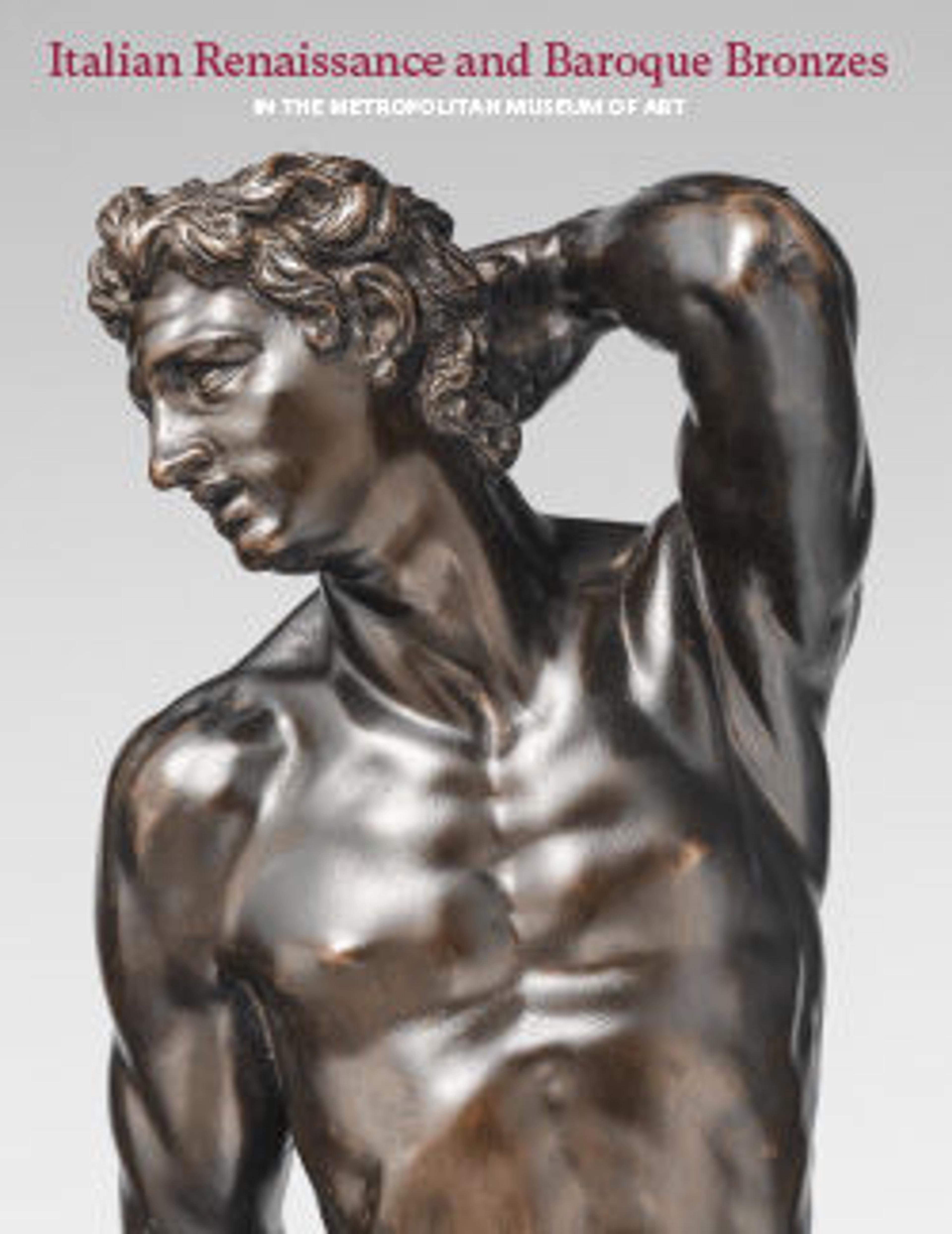

Samson and the Philistines

The statuette was acquired in 1957 by Irwin Untermyer, judge, attorney, and generous patron of The Met. A receipt for the purchase shows that Untermyer paid $6,000 for a “very rare bronze” with an earlier provenance in the “collection of Baron Gustave de Rothschild.”[1] While not offering an attribution, the receipt refers to Wilhelm von Bode’s publication Die italienischen Bronzestatuetten der Renaissance (1907–12), which illustrates a similar cast in the Bargello believed to have been after a model by Michelangelo.

Yvonne Hackenbroch published the Untermyer bronze in 1958 and again in 1962 with an attribution to the Florentine sculptor Pierino da Vinci, informed by the judgments of Leo Planiscig and Adolfo Venturi on analogous bronzes.[2] Indeed, Giorgio Vasari wrote that Pierino studied “some sketches by Michelangelo of Samson slaying a Philistine with the jawbone of an ass.”[3] Hackenbroch’s claim was refuted by John Pope-Hennessy and Anthony Radcliffe, who, avoiding an attribution to a single name, grouped our statuette with a corpus of technically and stylistically related bronzes.[4] In this context, an alternative proposal linking this corpus to the work of Daniele da Volterra was also rejected, though the artist cites the composition in his Massacre of the Innocents painted for San Pietro in Selci, Volterra, and in a fresco of the same subject for Santissima Trinità dei Monti, Rome, both executed in the mid-1550s.[5]

In fact, our bronze is part of a group of thirteen sculptures of varying dates and authorship with similar themes, designs, and dimensions that engage closely with one of Michelangelo’s grand unrealized projects.[6] A relationship has been established between this group of bronzes, which we will call the Samson corpus, and a terracotta model in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence.[7] This model has usually been considered Michelangelo’s primo pensiero for a large-scale marble to be installed alongside his David in Piazza della Signoria. Beginning in 1506, he began exploring ideas for a group of wrestling figures. The concept grew more complex during the 1520s and in conjunction with the founding of the Second Florentine Republic, eventually including a tangle of three figures representing the biblical hero Samson with the two Philistines (according to Vasari).[8] While the terracotta sketch comprises only a pair of adversaries, The Met’s inextricable knot of three fighters is based on a conceit of great formal audacity. The victorious bearded man is Samson, identified by the jawbone of an ass held aloft in his right hand. A similar attribute apears in other works in the Samson corpus, for example, those in the Frick and the Louvre, and one auctioned at Christie’s in 1990.[9] This detail links the corpus to Michelangelo’s preparatory work for the large statue of Samson and the Philistines, and it is possible that the bronzes derive from a second model, now lost, developed by him during the long period of reflection around the monumental sculptural group destined for Piazza della Signoria.

Eike Schmidt compiled the evidence for this lineage by systematically collating all the derivations from Michelangelo’s project—graphic, painted, sculptural.[10] In Schmidt’s analysis, the Samson corpus can be divided into two subgroups. The first, of which the exemplar is a statuette in the Bargello (286 B), is distinguished by a more sophisticated rendering of the figures and the dynamics of movement and countermovement. The second is marked by simplifications to the Bargello bronze’s design. Objects in this latter group are not variants per se, but rather reflect the type of modifications that are routinely made with the passing of time and in a chain of successive replicas.

The multiplication of copies attests to the fame of Michelangelo’s archetype, as do honorific references to it in works such as Federico Zuccari’s preparatory drawing for a portrait of Giambologna, depicting the sculptor holding the master’s model (1570s; National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh).[11] The model was copied in artists’ workshops, for instance, in a well-known series of drawings by Tintoretto (or his studio) that analyze Michelangelo’s figures from multiple viewpoints. The presence of a support in some of these drawings suggests that the object of study was a plaster model and not a bronze.[12]

Schmidt rightly believes that The Met Samson was made in the sixteenth century and positions it close to the Bargello exemplar and another bronze from the corpus in the Bode-Museum.[13] He thus implicitly endorses the high quality of our statuette claimed by Pope-Hennessy, who held it to be, together with the statuette in the Frick, one of the finest examples of the entire Samson group.

Richard Stone’s technical analysis of our bronze has shown the use of plaster for the core and investment, little evidence of wax-to-wax joins, and no signs of cold work on the surface.[14] Its octagonal base contrasts with the rectangular one supporting the Frick bronze. For that matter, the variability of bases across the Samson corpus suggests that the model from which they originated did not have a support.

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. ESDA/OF.

2. For documentation, see Pope-Hennessy 1970, pp. 190, 194 nn. 11–13.

3. Vasari 1906, vol. 6, p. 128: “alcuni schizzi di Michelagnolo d’un Sansone che ammazzava un Filisteo con la mascella d’asino.” The importance of this passage in relationship to Michelangelo’s oeuvre is underlined in Schlosser 1913, pp. 108–10.

4. Pope-Hennessy 1963b, p. 62; Pope-Hennessy 1970, p. 190. See also Radcliffe 1966, pp. 73–74.

5. On this attribution, see Schmidt 1996, pp. 82, 120 n. 15.

6. The group includes the following: Bode-Museum, 2389 (Bode and Knapp 1904, p. 7, no. 260); Bargello, 99 B and 286 B; private collection, London (incomplete; see ESDA/OF); Frick, 1916.2.40 (Pope-Hennessy 1970, pp. 186–95); Louvre, Thiers 106; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, BEK 1132 (Binnebeke 1994, p. 162, no. 52); Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMSK 342 (Larsson 1992, pp. 48–49, no. 15); Woburn Abbey (C. Avery 1984, p. 99); ex-Alexandre de Frey collection, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, June 12–14, 1933, lot 137; Christie’s, London, May 15, 1984, lot 161; ex-Peter Gilbert collection, Christie’s East, New York, May 30, 1990, lot 144; Sotheby’s, London, July 4, 1991, lot 138 (already auctioned at Sotheby’s, London, July 14, 1977, lot 187).

7. Inv. 19; see https://www.casabuonarroti.it/en/museum/collections/michelangelos-works/two-wrestlers/.

8. Vasari 1906, vol. 6, p. 155.

9. See note 6.

10. Schmidt 1996.

11. Ibid., pp. 79–80, 104–9.

12. See, most recently, Marciari 2018, pp. 102–3, 210.

13. Schmidt 1996, p. 84. See note 6.

14. R. Stone/TR, May 24, 2011. Stone notes the presence of modern threading on screw plugs and considers the bronze a nineteenth-century cast of a damaged wax model.

Yvonne Hackenbroch published the Untermyer bronze in 1958 and again in 1962 with an attribution to the Florentine sculptor Pierino da Vinci, informed by the judgments of Leo Planiscig and Adolfo Venturi on analogous bronzes.[2] Indeed, Giorgio Vasari wrote that Pierino studied “some sketches by Michelangelo of Samson slaying a Philistine with the jawbone of an ass.”[3] Hackenbroch’s claim was refuted by John Pope-Hennessy and Anthony Radcliffe, who, avoiding an attribution to a single name, grouped our statuette with a corpus of technically and stylistically related bronzes.[4] In this context, an alternative proposal linking this corpus to the work of Daniele da Volterra was also rejected, though the artist cites the composition in his Massacre of the Innocents painted for San Pietro in Selci, Volterra, and in a fresco of the same subject for Santissima Trinità dei Monti, Rome, both executed in the mid-1550s.[5]

In fact, our bronze is part of a group of thirteen sculptures of varying dates and authorship with similar themes, designs, and dimensions that engage closely with one of Michelangelo’s grand unrealized projects.[6] A relationship has been established between this group of bronzes, which we will call the Samson corpus, and a terracotta model in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence.[7] This model has usually been considered Michelangelo’s primo pensiero for a large-scale marble to be installed alongside his David in Piazza della Signoria. Beginning in 1506, he began exploring ideas for a group of wrestling figures. The concept grew more complex during the 1520s and in conjunction with the founding of the Second Florentine Republic, eventually including a tangle of three figures representing the biblical hero Samson with the two Philistines (according to Vasari).[8] While the terracotta sketch comprises only a pair of adversaries, The Met’s inextricable knot of three fighters is based on a conceit of great formal audacity. The victorious bearded man is Samson, identified by the jawbone of an ass held aloft in his right hand. A similar attribute apears in other works in the Samson corpus, for example, those in the Frick and the Louvre, and one auctioned at Christie’s in 1990.[9] This detail links the corpus to Michelangelo’s preparatory work for the large statue of Samson and the Philistines, and it is possible that the bronzes derive from a second model, now lost, developed by him during the long period of reflection around the monumental sculptural group destined for Piazza della Signoria.

Eike Schmidt compiled the evidence for this lineage by systematically collating all the derivations from Michelangelo’s project—graphic, painted, sculptural.[10] In Schmidt’s analysis, the Samson corpus can be divided into two subgroups. The first, of which the exemplar is a statuette in the Bargello (286 B), is distinguished by a more sophisticated rendering of the figures and the dynamics of movement and countermovement. The second is marked by simplifications to the Bargello bronze’s design. Objects in this latter group are not variants per se, but rather reflect the type of modifications that are routinely made with the passing of time and in a chain of successive replicas.

The multiplication of copies attests to the fame of Michelangelo’s archetype, as do honorific references to it in works such as Federico Zuccari’s preparatory drawing for a portrait of Giambologna, depicting the sculptor holding the master’s model (1570s; National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh).[11] The model was copied in artists’ workshops, for instance, in a well-known series of drawings by Tintoretto (or his studio) that analyze Michelangelo’s figures from multiple viewpoints. The presence of a support in some of these drawings suggests that the object of study was a plaster model and not a bronze.[12]

Schmidt rightly believes that The Met Samson was made in the sixteenth century and positions it close to the Bargello exemplar and another bronze from the corpus in the Bode-Museum.[13] He thus implicitly endorses the high quality of our statuette claimed by Pope-Hennessy, who held it to be, together with the statuette in the Frick, one of the finest examples of the entire Samson group.

Richard Stone’s technical analysis of our bronze has shown the use of plaster for the core and investment, little evidence of wax-to-wax joins, and no signs of cold work on the surface.[14] Its octagonal base contrasts with the rectangular one supporting the Frick bronze. For that matter, the variability of bases across the Samson corpus suggests that the model from which they originated did not have a support.

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. ESDA/OF.

2. For documentation, see Pope-Hennessy 1970, pp. 190, 194 nn. 11–13.

3. Vasari 1906, vol. 6, p. 128: “alcuni schizzi di Michelagnolo d’un Sansone che ammazzava un Filisteo con la mascella d’asino.” The importance of this passage in relationship to Michelangelo’s oeuvre is underlined in Schlosser 1913, pp. 108–10.

4. Pope-Hennessy 1963b, p. 62; Pope-Hennessy 1970, p. 190. See also Radcliffe 1966, pp. 73–74.

5. On this attribution, see Schmidt 1996, pp. 82, 120 n. 15.

6. The group includes the following: Bode-Museum, 2389 (Bode and Knapp 1904, p. 7, no. 260); Bargello, 99 B and 286 B; private collection, London (incomplete; see ESDA/OF); Frick, 1916.2.40 (Pope-Hennessy 1970, pp. 186–95); Louvre, Thiers 106; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, BEK 1132 (Binnebeke 1994, p. 162, no. 52); Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, NMSK 342 (Larsson 1992, pp. 48–49, no. 15); Woburn Abbey (C. Avery 1984, p. 99); ex-Alexandre de Frey collection, Galerie Charpentier, Paris, June 12–14, 1933, lot 137; Christie’s, London, May 15, 1984, lot 161; ex-Peter Gilbert collection, Christie’s East, New York, May 30, 1990, lot 144; Sotheby’s, London, July 4, 1991, lot 138 (already auctioned at Sotheby’s, London, July 14, 1977, lot 187).

7. Inv. 19; see https://www.casabuonarroti.it/en/museum/collections/michelangelos-works/two-wrestlers/.

8. Vasari 1906, vol. 6, p. 155.

9. See note 6.

10. Schmidt 1996.

11. Ibid., pp. 79–80, 104–9.

12. See, most recently, Marciari 2018, pp. 102–3, 210.

13. Schmidt 1996, p. 84. See note 6.

14. R. Stone/TR, May 24, 2011. Stone notes the presence of modern threading on screw plugs and considers the bronze a nineteenth-century cast of a damaged wax model.

Artwork Details

- Title: Samson and the Philistines

- Artist: After a model by Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, Caprese 1475–1564 Rome)

- Date: ca. 1550

- Culture: Italian, Florence

- Medium: Bronze

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 14 7/8 × 7 1/8 × 6 1/4 in. (37.8 × 18.1 × 15.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964

- Object Number: 64.101.1444

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.