Charity

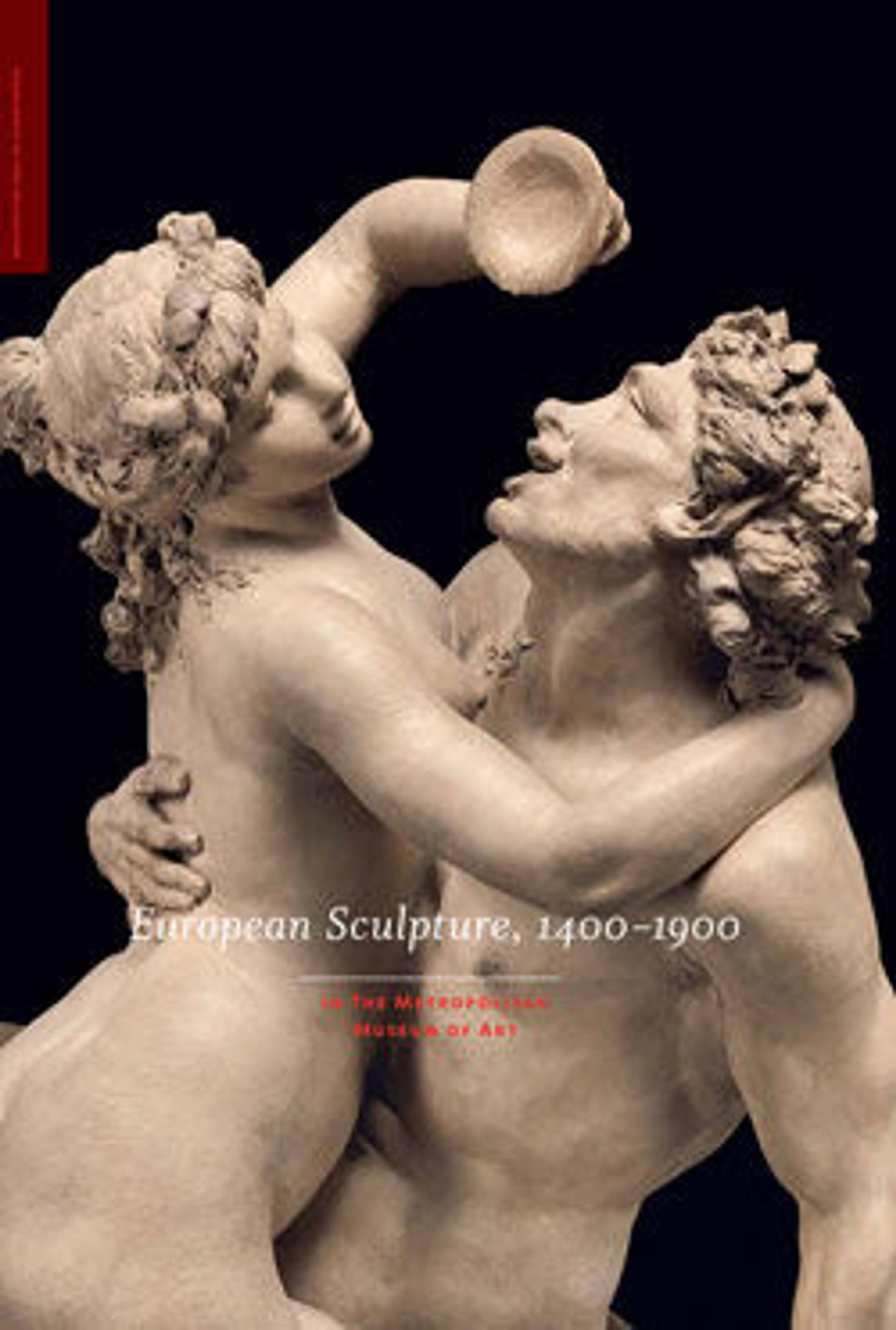

This allegorical figure of Charity nurtures three children. One clambers up her blouse to reach her left breast; one she pins with one arm to her left hip; the eldest stands at her feet, twisting to look up at his brother. Standing calmly amid her wriggling brood, the woman looks down with a trace of a smile. She wears a laurel wreath on her long hair. Lifting her robe, which is trimmed at the hem with a rinceau border, she reveals sandals decorated with seraphim heads. In its iconography, this Charity is related to the type of statue that stood in the loft or gallery atop the screen that separated the altar of a church from the congregation and also supported a crucifix, or rood. The Charity carved in 1550 – 52 by Domenico del Barbiere for the stone rood screen that once stood in the church of Saint-Étienne (now Saint-Pantaléon), Troyes, has three children tucked into the folds of her voluminous robe.[1] Another example, carved by the Flemish sculptor and architect Jacques Du Broeucq between 1535 and 1548 and still in the collegiate church of Sainte-Waudru, Mons, is accompanied by two children, one nestled in her arms, one standing at her feet.[2]

It seems probable that, like the two works just described, the Museum’s statue was once part of an architectural structure inside a church. The sculptural programs of rood screens varied in complexity. At Troyes, Charity and Faith flanked the crucifix (in addition to the Virgin and Saint John Evangelist); at Mons, the group around the crucifix included the theological and the temporal virtues. Called jubés in France, these stone or wood screens figured frequently in European churches early in the sixteenth century, but after the Council of Trent (1545 – 63) they were often torn down as obstacles to the newly desirable proximity between laity and clergy. This Charity’s fine alabaster with traces of gilding and its good condition suggest that the sculpture originally stood indoors and continued to be protected from the weather.

Since this type of architectural statue is predominantly found in northern France and the Low Countries, the sculptor has been sought in that region. Not unreasonably, the French artist Germain Pilon (ca. 1525 – 1590) was first considered its creator.[3] To those scholars who attributed it to Pilon, the Charity seemed to have the courtly grace and mannered line associated with art at the court of Fontainebleau in the middle of the sixteenth century. Comparisons have been made with the sculpture of Du Broeucq (ca. 1505 – 1584), who often worked in alabaster, a material abundant in Flanders. The stately virtues he carved for Sainte-Waudru in Mons have many points of comparison with the Museum’s Charity. Their straightforward poses are enlivened by drapery that clings to the torso in many fine pleats but sweeps around the legs in broader swaths. The Museum’s Charity does not have the broad, sharp eyebrows characteristic of the Mons statues, and her children have lumpier muscles and more awkward poses than the graceful wards of the Sainte-Waudru Charity. But its refined carving and keen formal sense suggest the hand of an accomplished artist familiar with Du Broeucq’s style.

A third sculptor, the German Conrad Meit (1480s – 1550/51), has been mentioned in connection with this Charity.[4] Meit worked in the same region as Du Broeucq, particularly at the church of Brou, near Bourg-en-Bresse, where his Sybil, or Virtue, of 1532 decorates the tomb of Margaret of Austria. Its sweet demeanor is reminiscent of our Charity. The precision and geometric patterns in Meit’s carving of pleats, however, do not seem quite matched in the more relaxed flow of this Charity’s drapery.

Recently, Jens Burk proposed a fourth candidate, Claudius Floris (died after 1548).[5] Dean of the guild of Saint Luke (a professional organization of painters, sculptors, and other artists) in Antwerp, he was responsible for the sculptural images at the top of the sacramental tower in the abbey church of Tongerlo in Flanders. This fifty-foot-high structure executed between 1536 and 1547/48 supported some five hundred statues and statuettes until it was destroyed in 1797. No images of the original monument are known, and only a few of its sculptural decorations, including some of Meit’s work, survive. Fredericus van Houdt, prior of the Norbertine abbey of Tongerlo, in 1779 described three fairly tall alabaster statues of Faith, Love, and Hope standing on a level above Meit’s statues. Furthermore, a 1798 inventory of works in the Carmelite convent at Antwerp noted an alabaster statue of "Love with three children" ("Love" is the literal translation of Caritas, the Latin word for charity), a hint that it may have escaped the demolition the previous year. Although there are no certain extant works by Claudius Floris, Burk’s research establishes circumstantial evidence that he may have been the sculptor responsible for the Museum’s Charity. Further research may yield proof of this hypothesis.

Although the question of attribution remains open, it seems correct to say that this probably mid-sixteenth-century statue once stood on an architectural screen or tower at a church in northern France or southern Flanders. Whoever was the artist responsible, the sculpture, at once graceful and compelling, is perhaps the finest and most imposing alabaster carving of this period in an American museum.

[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 24, pp. 77–79.]

Footnotes:

1. Ian Wardropper. "New Attributions for Domenico del Barbiere’s Jubé at Saint-Étienne, Troyes." Gazette des beaux-arts, 6th ser., 118 (October 1991), pp. 111–28.

2. Collégiale Sainte-Waudru, Mons (Robert Didier in Jacques Du Broeucq, sculpteur et architecte de la Renaissance: Recueil d’études publié en commemoration du quatrième centenaire du décès de l’artiste. Exh. cat. Collégiale Sainte-Warudru, Mons; 1985. Mons, 1985, p. 59, no. n9s, ill. p. 58).

3. "A Marble Statue by Germain Pilon." Burlington Magazine 2, no. 4 (June 1903), pp. 90–95, p. 95; Hans Vollmer. Jean Goujon und die französische Renaissanceskulptur. Bibliothek der Kunstgeschichte 53. Leipzig, 1923, fig. 19; "Pilon (Pillon), Germain." In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, vol. 27, pp. 44–46. Leipzig, 1933, p. 45; John Goldsmith Phillips. "Reports of the Departments: Western European Arts." In "Ninety-fifth Annual Report of the Trustees for the Fiscal year 1964–1965," pp. 76–79. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, n.s., 24, no. 2 (October 1965), pp. 76 – 77, 79.

4. Important Sculpture and Works of Art, including Reference Books and Neapolitan Crib Figures. Sale cat. Christie’s, London, April 21, 1982, p. 60, no. 149.

5. Jens Ludwig Burk. "Some Remarks on Conrat Meit and South Netherlandish Sculpture between 1533 and 1566." Paper delivered at the conference "Renaissance Sculpture of the Low Countries from the Century of Jacques Du Broeucq (c. 1505–84)," Held in Mons, March 7–10, 2008.

It seems probable that, like the two works just described, the Museum’s statue was once part of an architectural structure inside a church. The sculptural programs of rood screens varied in complexity. At Troyes, Charity and Faith flanked the crucifix (in addition to the Virgin and Saint John Evangelist); at Mons, the group around the crucifix included the theological and the temporal virtues. Called jubés in France, these stone or wood screens figured frequently in European churches early in the sixteenth century, but after the Council of Trent (1545 – 63) they were often torn down as obstacles to the newly desirable proximity between laity and clergy. This Charity’s fine alabaster with traces of gilding and its good condition suggest that the sculpture originally stood indoors and continued to be protected from the weather.

Since this type of architectural statue is predominantly found in northern France and the Low Countries, the sculptor has been sought in that region. Not unreasonably, the French artist Germain Pilon (ca. 1525 – 1590) was first considered its creator.[3] To those scholars who attributed it to Pilon, the Charity seemed to have the courtly grace and mannered line associated with art at the court of Fontainebleau in the middle of the sixteenth century. Comparisons have been made with the sculpture of Du Broeucq (ca. 1505 – 1584), who often worked in alabaster, a material abundant in Flanders. The stately virtues he carved for Sainte-Waudru in Mons have many points of comparison with the Museum’s Charity. Their straightforward poses are enlivened by drapery that clings to the torso in many fine pleats but sweeps around the legs in broader swaths. The Museum’s Charity does not have the broad, sharp eyebrows characteristic of the Mons statues, and her children have lumpier muscles and more awkward poses than the graceful wards of the Sainte-Waudru Charity. But its refined carving and keen formal sense suggest the hand of an accomplished artist familiar with Du Broeucq’s style.

A third sculptor, the German Conrad Meit (1480s – 1550/51), has been mentioned in connection with this Charity.[4] Meit worked in the same region as Du Broeucq, particularly at the church of Brou, near Bourg-en-Bresse, where his Sybil, or Virtue, of 1532 decorates the tomb of Margaret of Austria. Its sweet demeanor is reminiscent of our Charity. The precision and geometric patterns in Meit’s carving of pleats, however, do not seem quite matched in the more relaxed flow of this Charity’s drapery.

Recently, Jens Burk proposed a fourth candidate, Claudius Floris (died after 1548).[5] Dean of the guild of Saint Luke (a professional organization of painters, sculptors, and other artists) in Antwerp, he was responsible for the sculptural images at the top of the sacramental tower in the abbey church of Tongerlo in Flanders. This fifty-foot-high structure executed between 1536 and 1547/48 supported some five hundred statues and statuettes until it was destroyed in 1797. No images of the original monument are known, and only a few of its sculptural decorations, including some of Meit’s work, survive. Fredericus van Houdt, prior of the Norbertine abbey of Tongerlo, in 1779 described three fairly tall alabaster statues of Faith, Love, and Hope standing on a level above Meit’s statues. Furthermore, a 1798 inventory of works in the Carmelite convent at Antwerp noted an alabaster statue of "Love with three children" ("Love" is the literal translation of Caritas, the Latin word for charity), a hint that it may have escaped the demolition the previous year. Although there are no certain extant works by Claudius Floris, Burk’s research establishes circumstantial evidence that he may have been the sculptor responsible for the Museum’s Charity. Further research may yield proof of this hypothesis.

Although the question of attribution remains open, it seems correct to say that this probably mid-sixteenth-century statue once stood on an architectural screen or tower at a church in northern France or southern Flanders. Whoever was the artist responsible, the sculpture, at once graceful and compelling, is perhaps the finest and most imposing alabaster carving of this period in an American museum.

[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 24, pp. 77–79.]

Footnotes:

1. Ian Wardropper. "New Attributions for Domenico del Barbiere’s Jubé at Saint-Étienne, Troyes." Gazette des beaux-arts, 6th ser., 118 (October 1991), pp. 111–28.

2. Collégiale Sainte-Waudru, Mons (Robert Didier in Jacques Du Broeucq, sculpteur et architecte de la Renaissance: Recueil d’études publié en commemoration du quatrième centenaire du décès de l’artiste. Exh. cat. Collégiale Sainte-Warudru, Mons; 1985. Mons, 1985, p. 59, no. n9s, ill. p. 58).

3. "A Marble Statue by Germain Pilon." Burlington Magazine 2, no. 4 (June 1903), pp. 90–95, p. 95; Hans Vollmer. Jean Goujon und die französische Renaissanceskulptur. Bibliothek der Kunstgeschichte 53. Leipzig, 1923, fig. 19; "Pilon (Pillon), Germain." In Allgemeines Lexikon der bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker, vol. 27, pp. 44–46. Leipzig, 1933, p. 45; John Goldsmith Phillips. "Reports of the Departments: Western European Arts." In "Ninety-fifth Annual Report of the Trustees for the Fiscal year 1964–1965," pp. 76–79. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, n.s., 24, no. 2 (October 1965), pp. 76 – 77, 79.

4. Important Sculpture and Works of Art, including Reference Books and Neapolitan Crib Figures. Sale cat. Christie’s, London, April 21, 1982, p. 60, no. 149.

5. Jens Ludwig Burk. "Some Remarks on Conrat Meit and South Netherlandish Sculpture between 1533 and 1566." Paper delivered at the conference "Renaissance Sculpture of the Low Countries from the Century of Jacques Du Broeucq (c. 1505–84)," Held in Mons, March 7–10, 2008.

Artwork Details

- Title: Charity

- Artist: Attributed to Claudius Floris (Flemish, after 1548)

- Former Attribution: Circle of Jacques du Broeucq (ca. 1500–1584)

- Date: 1536–1547/48

- Culture: Flemish, Antwerp (?)

- Medium: Alabaster, traces of gilding

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): H. 54 3/4 x W. 17 1/2 x D. 12 3/8 in. (139.1 x 44.5 x 31.4 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture

- Credit Line: Purchase, Josephine Bay Paul and C. Michael Paul Foundation Inc. Gift and Charles Ulrick and Josephine Bay Foundation Inc. Gift, 1965

- Object Number: 65.110

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.