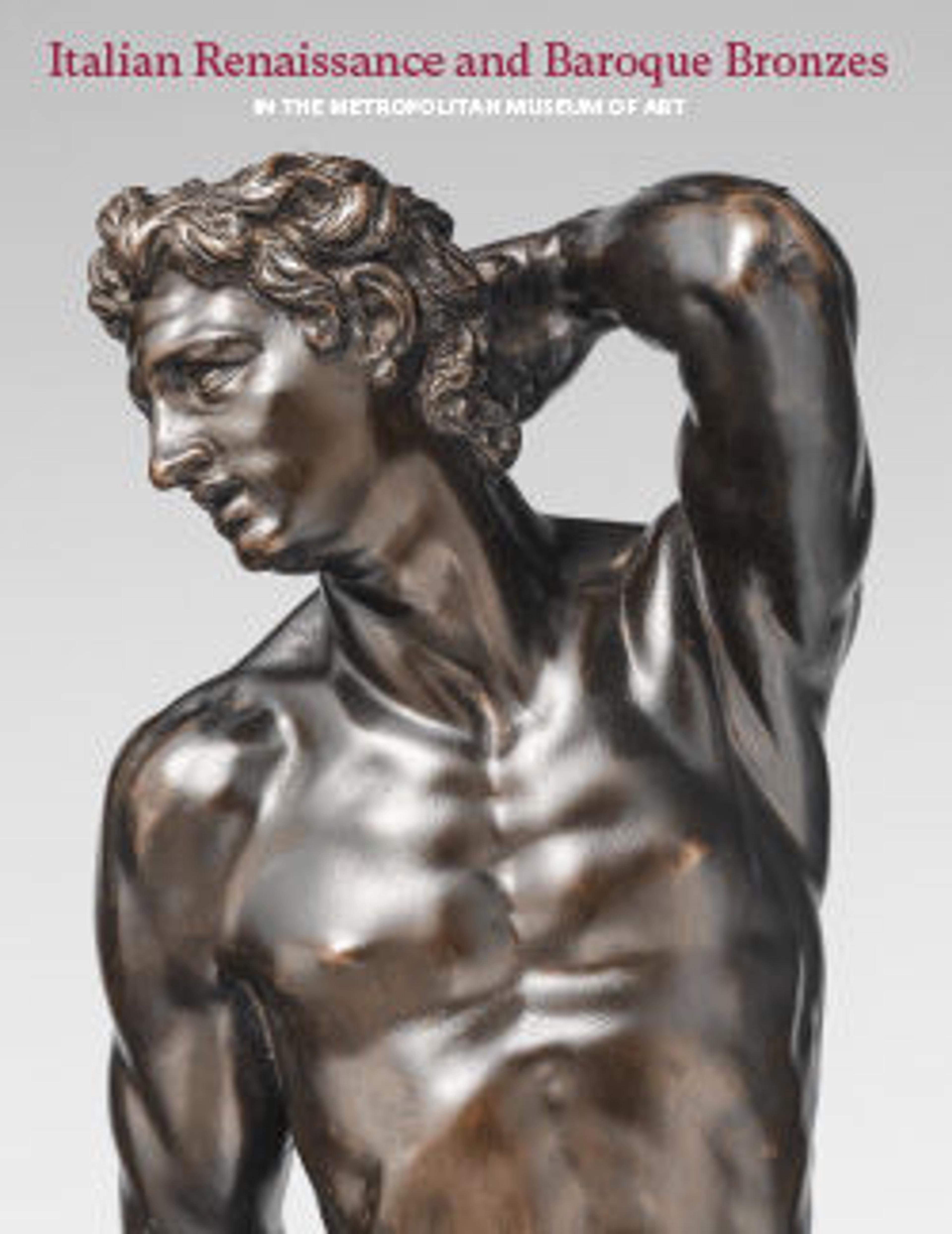

Seated male figure

From an unknown date until the 1920s, our male figure resided in the Villa Garzoni in Pontecasale, south of Padua. As documented in a photograph published in 1909 (fig. 107a), the bronze was centered on the mantel of a monumental fireplace as part of a Neoclassical arrangement of obelisks, antique profiles, and reliefs. The sculpture was mounted on a “naturalistic” base in a rocklike formation that, together with the leafy frame of the mantel backdrop, evoked a rustic environment.

According to Giorgio Vasari, the villa was designed by Jacopo Sansovino for the Venetian Garzoni family in the 1540s and 1550s.[1] The villa changed hands over the centuries, from the Garzoni to the Michiel, Martinengo, and Donà dalle Rose families.[2] In the 1935 sale of the Donà dalle Rose collection, the bronze was not among the pieces on offer, nor did it appear in the catalogue photograph showing the fireplace.[3] However, in the years immediately preceding the auction, the bronze had achieved a degree of fame thanks to an article by Adolfo Callegari about the villa and its treasures, published in 1926, where the statuette was reproduced twice and possibly caught the eye of a connoisseur.[4] An undated French & Company photograph shows the figure seated on the same rocky plinth as in the 1909 image (fig. 107b). Beyond confirming its placement with this well-known New York art dealer, the photo suggests that the piece had been introduced into the American market soon upon its removal from the Villa Garzoni.

In any case, at some point the sculpture entered the collection of Sarah Mellon Scaife, niece of the banker and politician Andrew W. Mellon. Following her death in 1965, it was sold to The Met and lauded as an important creation by a sixteenth-century Florentine artist, probably Bartolomeo Ammannati, following Callegari and subsequent Italian studies dedicated to the Tuscan sculptor from Settignano.[5] Ammannati had worked on Venetian projects overseen by Sansovino in the early 1540s, which is to say in the same years that the elder master designed the villa in Pontecasale.[6] In fact, while the bronze was still in Scaife’s possession, it was celebrated as a work by Sansovino,[7] and despite its continued parallel association with Ammannati or his circle, scholars are still divided regarding its paternity.[8] Moreover, its attribution is complicated by the fact that another version of the statuette in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, had been assigned to the Flemish sculptor Adriaen de Vries and only recently resituated in an Italian context.[9]

What is certain is that the figurative language that informs our bronze derives from Florentine inspirations, all of which can be found in the early sixteenth century. The literature notes correspondences to Michelangelo’s cartoon and preparatory drawings for the Battle of Cascina, in particular a study in the British Museum.[10] Just as convincing are references to the corpus of drawings by Baccio Bandinelli (see, in particular, Louvre, INV 92r) and to the bronze satyrs seated on the rim of the basin of the Fountain of Neptune in Piazza della Signoria. With its muscular and serpentine pose, our male figure is an eloquent and exemplary synthesis of the culture emanating from Michelangelo’s work. In a discussion of the Braunschweig bronze and a suggested attribution to Alessandro Vittoria, Charles Davis underlined the rapid dissemination of this Michelangelesque culture far beyond Florence in the first half of the century.[11] For that matter, Alan Darr had already pointed to certain formal affinities between The Met bronze and a Mars and Neptune at the Detroit Institute of Arts whose provenance is the Palazzo Rezzonico in Venice, in particular the pictorial quality of the beard and hair and the anatomical rendering of the chest and flanks.12 Although it is difficult to attribute the three statues to the same hand (Darr gave them all to Danese Cattaneo), it is true nonetheless that the stylistic concordance among details might be traced to a common production locale.

All that being said, no documentary evidence places our statuette in the Villa Garzoni at the time of its construction. Given the figure’s small size—which distinguishes it from Sansovino’s imposing furnishings—we cannot exclude the possibility that it was made at a later date, perhaps as a commission to an artist not directly linked to the villa project. The “open” pose of the figure, as if caught in the act of moving backward or away from an opposing force, suggests that originally it could have been part of a more complex ensemble.

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Vasari 1912–15, vol. 9, pp. 218–19. For the history of the villa, see Puppi 1969.

2. Puppi 1969, p. 95.

3. Lorenzetti and Planiscig 1934, fig. 77.

4. Callegari 1925–26, pp. 582–83, 588–90.

5. Draper in MMA 1975, p. 235; Callegari 1925–26, pp. 582–83, 588–90; Gabrielli 1937, p. 90; Bettini 1940–41, p. 20.

6. Cherubini 2011, p. 60.

7. “Sarah Mellon Scaife Collection Will Be Sold by Parke-Bernet,” The New York Times, September 25, 1966.

8. Krahn in Paolozzi Strozzi and Zikos 2011, pp. 430–31 n. 25.

9. The two versions are of similar dimensions, but differ in the quality of casting, and the patina on our bronze is very damaged (ESDA/OF, April 28, 1967). For the Braunschweig cast (Bro 40), see Brinckmann 1919, vol. 2, p. 409; Jacob 1972, pp. 15–16, no. 24; Berger and Krahn 1994, pp. 70–74, no. 36.

10. For Michelangelo’s cartoon, see Callegari 1925–26, p. 590; for a drawing in the British Museum, (1887,0502.116), see Berger and Krahn 1994, p. 73.

11. Davis 2011, p. 558.

12. DIA, 49.417, .418; see Darr 2003, p. 227.

According to Giorgio Vasari, the villa was designed by Jacopo Sansovino for the Venetian Garzoni family in the 1540s and 1550s.[1] The villa changed hands over the centuries, from the Garzoni to the Michiel, Martinengo, and Donà dalle Rose families.[2] In the 1935 sale of the Donà dalle Rose collection, the bronze was not among the pieces on offer, nor did it appear in the catalogue photograph showing the fireplace.[3] However, in the years immediately preceding the auction, the bronze had achieved a degree of fame thanks to an article by Adolfo Callegari about the villa and its treasures, published in 1926, where the statuette was reproduced twice and possibly caught the eye of a connoisseur.[4] An undated French & Company photograph shows the figure seated on the same rocky plinth as in the 1909 image (fig. 107b). Beyond confirming its placement with this well-known New York art dealer, the photo suggests that the piece had been introduced into the American market soon upon its removal from the Villa Garzoni.

In any case, at some point the sculpture entered the collection of Sarah Mellon Scaife, niece of the banker and politician Andrew W. Mellon. Following her death in 1965, it was sold to The Met and lauded as an important creation by a sixteenth-century Florentine artist, probably Bartolomeo Ammannati, following Callegari and subsequent Italian studies dedicated to the Tuscan sculptor from Settignano.[5] Ammannati had worked on Venetian projects overseen by Sansovino in the early 1540s, which is to say in the same years that the elder master designed the villa in Pontecasale.[6] In fact, while the bronze was still in Scaife’s possession, it was celebrated as a work by Sansovino,[7] and despite its continued parallel association with Ammannati or his circle, scholars are still divided regarding its paternity.[8] Moreover, its attribution is complicated by the fact that another version of the statuette in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, had been assigned to the Flemish sculptor Adriaen de Vries and only recently resituated in an Italian context.[9]

What is certain is that the figurative language that informs our bronze derives from Florentine inspirations, all of which can be found in the early sixteenth century. The literature notes correspondences to Michelangelo’s cartoon and preparatory drawings for the Battle of Cascina, in particular a study in the British Museum.[10] Just as convincing are references to the corpus of drawings by Baccio Bandinelli (see, in particular, Louvre, INV 92r) and to the bronze satyrs seated on the rim of the basin of the Fountain of Neptune in Piazza della Signoria. With its muscular and serpentine pose, our male figure is an eloquent and exemplary synthesis of the culture emanating from Michelangelo’s work. In a discussion of the Braunschweig bronze and a suggested attribution to Alessandro Vittoria, Charles Davis underlined the rapid dissemination of this Michelangelesque culture far beyond Florence in the first half of the century.[11] For that matter, Alan Darr had already pointed to certain formal affinities between The Met bronze and a Mars and Neptune at the Detroit Institute of Arts whose provenance is the Palazzo Rezzonico in Venice, in particular the pictorial quality of the beard and hair and the anatomical rendering of the chest and flanks.12 Although it is difficult to attribute the three statues to the same hand (Darr gave them all to Danese Cattaneo), it is true nonetheless that the stylistic concordance among details might be traced to a common production locale.

All that being said, no documentary evidence places our statuette in the Villa Garzoni at the time of its construction. Given the figure’s small size—which distinguishes it from Sansovino’s imposing furnishings—we cannot exclude the possibility that it was made at a later date, perhaps as a commission to an artist not directly linked to the villa project. The “open” pose of the figure, as if caught in the act of moving backward or away from an opposing force, suggests that originally it could have been part of a more complex ensemble.

-TM

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. Vasari 1912–15, vol. 9, pp. 218–19. For the history of the villa, see Puppi 1969.

2. Puppi 1969, p. 95.

3. Lorenzetti and Planiscig 1934, fig. 77.

4. Callegari 1925–26, pp. 582–83, 588–90.

5. Draper in MMA 1975, p. 235; Callegari 1925–26, pp. 582–83, 588–90; Gabrielli 1937, p. 90; Bettini 1940–41, p. 20.

6. Cherubini 2011, p. 60.

7. “Sarah Mellon Scaife Collection Will Be Sold by Parke-Bernet,” The New York Times, September 25, 1966.

8. Krahn in Paolozzi Strozzi and Zikos 2011, pp. 430–31 n. 25.

9. The two versions are of similar dimensions, but differ in the quality of casting, and the patina on our bronze is very damaged (ESDA/OF, April 28, 1967). For the Braunschweig cast (Bro 40), see Brinckmann 1919, vol. 2, p. 409; Jacob 1972, pp. 15–16, no. 24; Berger and Krahn 1994, pp. 70–74, no. 36.

10. For Michelangelo’s cartoon, see Callegari 1925–26, p. 590; for a drawing in the British Museum, (1887,0502.116), see Berger and Krahn 1994, p. 73.

11. Davis 2011, p. 558.

12. DIA, 49.417, .418; see Darr 2003, p. 227.

Artwork Details

- Title:Seated male figure

- Date:mid-16th century

- Culture:Central Italian

- Medium:Bronze

- Dimensions:Overall figure, confirmed: 15 3/4 × 12 3/4 × 19 1/4 in. (40 × 32.4 × 48.9 cm)

Max dims, as mounted on base, confirmed: 22 1/4 × 12 1/2 × 21 1/2 in., 32.2 lb. (56.5 × 31.8 × 54.6 cm, 14.6 kg)

Base only, confirmed: 10 1/8 in. × 12 1/2 in. × 10 in. (25.7 × 31.8 × 25.4 cm) - Classification:Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line:Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1966

- Object Number:66.177

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.