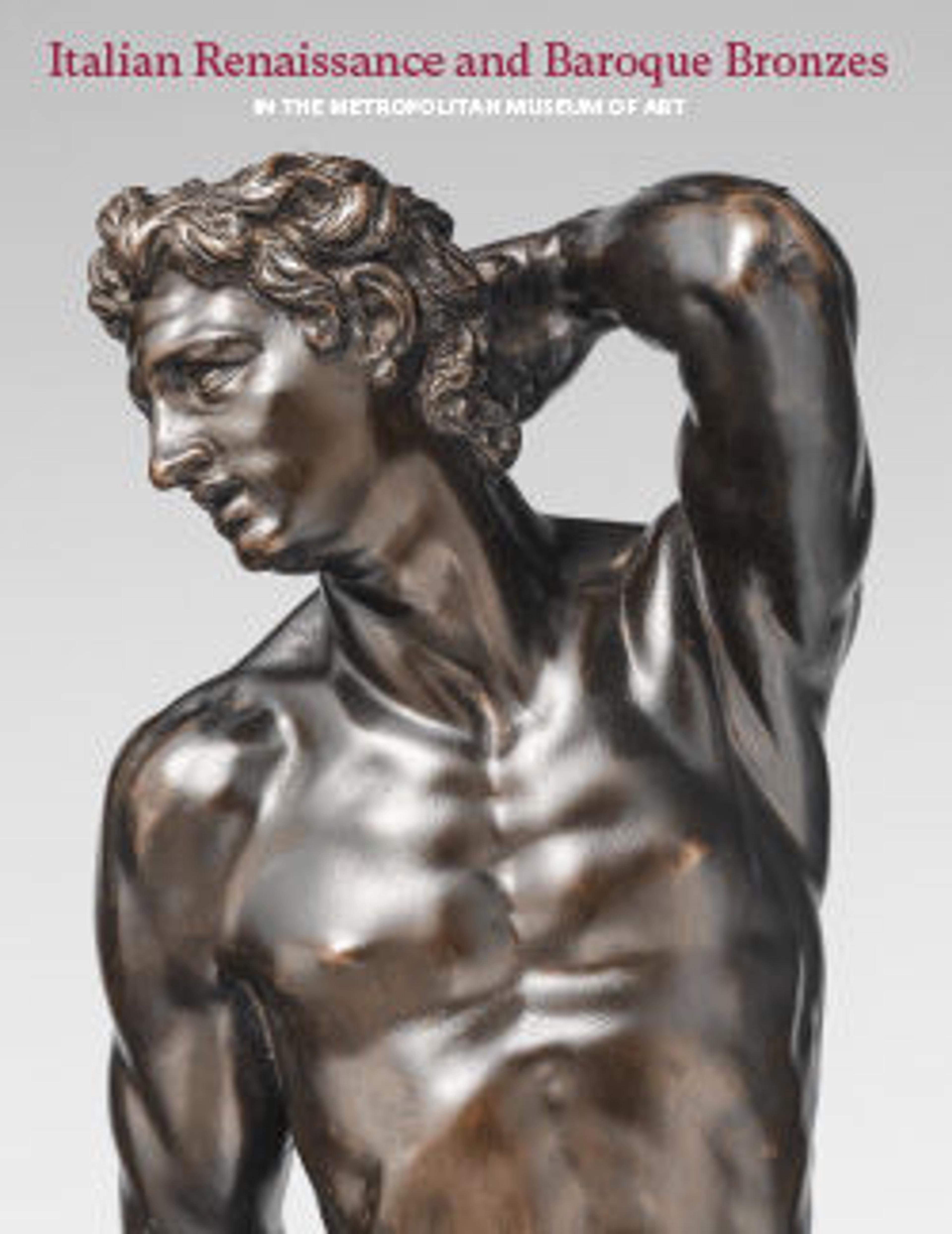

Seated goddess holding flowers (Flora?)

This partially draped female figure seated with her left leg slung over her knee represents a statuette type popular in northern Italy and the Veneto during the first half of the sixteenth century. The numerous bronze examples either derive from or were inspired by the model for the seated Nymph that had been created almost two generations before by the sculptor to the Gonzaga court in Mantua, Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi, known as Antico (p. 00, fig. 9b).[1] Stylistically, the Seated Goddess is many steps removed from Antico’s Nymph, yet even this late variant unmistakably reflects the earlier figure’s distinctive pose, disposition of drapery, and placement upon a massive, knotted tree trunk. Elements that diverge from Antico’s statuette are limited to the bunch of flowers our goddess clasps on her lap and her lavishly tressed head, crowned with a diadem and draped with strings of pearls. The Gonzaga prevented the distribution of Antico’s sculptural models and kept the number of his bronzes small and exclusive to their courts.[2] Of all his compositions, only the seated Nymph was so widely disseminated. When, how, and who initially purloined Antico’s invention likely always will remain mysterious. Its frequent reflection in later bronzes such as the Goddess speaks to the existence of a broad network of artistic exchange among anonymous sculptors and founders and to a substantial audience of collectors ready to acquire their works.

Richard Stone’s technical examination of The Met bronze suggests that it was made in Padua.[3] This location of origin is reinforced by the statuette’s type of elaborately bejeweled head that was invented by the city’s most important bronze sculptor, Andrea Riccio, and emulated by an expanding circle of minor masters.[4] Padua’s independent art foundries generated legions of statuettes.[5] The Goddess represents the kind of average product expected from a cottage industry: the modeling of the figure, facial features, and drapery is generalized; and the smooth, minimally worked metal surface lacks the time-consuming hammering characteristic of bronzes executed by Riccio and his close followers. Far removed from the essence of Riccio’s art, the Goddess likely dates toward the middle of the century, some years after the master’s death.

The Goddess may have been made as a cheaper alternative to the rare, costly ancient statuettes so prized by elite Renaissance collectors. The Venetian patrician Marcantonio Michiel, for example, recorded seeing seated bronze figures of classical Roman gods while visiting the important collections of Niccolò Leonico Tomeo and Pietro Bembo in Padua.[6] During Antico’s and Riccio’s lifetimes, their statuettes enjoyed the same classical authority as genuine antiquities and in later decades were confused with them. These circumstances endowed a hybrid pastiche like the Goddess with a powerful aura of classical credibility. However, the anonymous sculptor of this bronze also proved to be surprisingly inventive in his efforts to convey his ancient subject. His figure, more frontal than Antico’s, evokes the dignified posture of a deity; her outsized ornate diadem signifies she is a goddess; and the blossoms that she holds are probably attributes identifying her as Flora, goddess of flowers and springtime.

The unknown sculptor’s emphasis on clarity, specificity, and ease of apprehension depart from the often poetic ambiguity of Antico and the recondite antiquarianism of Riccio. Our Goddess aligns instead with the developing impulse toward classifying classical imagery expressed, for example, in Vincenzo Cartari’s groundbreaking mythological compendium, Le imagini con la spositione de i dei de gli antichi (Images Depicting the Gods of the Ancients), first published in 1556 in Venice. Intended for a general audience, the book was written in vernacular Italian rather than scholarly Latin, and even its earliest unillustrated editions were best-sellers.[7] Modest bronzes like the Goddess, which were produced in large numbers for the affordable end of the collecting market and designed in a novel colloquially classical mode, anticipated and may even have informed Cartari and later writers’ popularization of the ancient visual world.

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See Allison 1993–94, pp. 183–200, for the history of the replication of Antico’s Nymph and catalogue entries on all known versions.

2. See Luciano 2011, p. 7.

3. The statuette is a brass alloy with round, symmetrically placed, heavy wire core pins, most of which were replaced with copper alloy pins of square section driven into round holes, and a core that appears to have been clay, all features generally consistent with Paduan facture. R. Stone/TR, September 23, 2011.

4. For the possible origins of this type of head in the Seated Woman of ca. 1480–90 in the Wallace Collection (S72) by Giovanni Fonduli da Crema, who may have been Riccio’s teacher, see Warren 2016, vol. 1, pp. 190–201, no. 48. For the transmission of this head type through Riccio and his followers’ workshops, see most recently Wengraf 2018, pp. 8–15, cat. 1.

5. See Motture 2008, pp. 66–67.

6. Michiel 1888, p. 16: “in casa de M. Leonico Thomeo Phylosopho . . . Lo Giove piccolo di bronzo che siede, alla guisa del Giove del Bembo, ma minore, è opera anticha”; pp. 20, 22: “In casa di Misser Pietro Bembo . . . Il Giove picolo dibronzo che siede è opera anticha.”

7. For the publication history of Cartari’s Imagini, see https://bivio.signum.sns.it/html/editions/it/EdInfoCartari_Imagini_Dei.xml.

Richard Stone’s technical examination of The Met bronze suggests that it was made in Padua.[3] This location of origin is reinforced by the statuette’s type of elaborately bejeweled head that was invented by the city’s most important bronze sculptor, Andrea Riccio, and emulated by an expanding circle of minor masters.[4] Padua’s independent art foundries generated legions of statuettes.[5] The Goddess represents the kind of average product expected from a cottage industry: the modeling of the figure, facial features, and drapery is generalized; and the smooth, minimally worked metal surface lacks the time-consuming hammering characteristic of bronzes executed by Riccio and his close followers. Far removed from the essence of Riccio’s art, the Goddess likely dates toward the middle of the century, some years after the master’s death.

The Goddess may have been made as a cheaper alternative to the rare, costly ancient statuettes so prized by elite Renaissance collectors. The Venetian patrician Marcantonio Michiel, for example, recorded seeing seated bronze figures of classical Roman gods while visiting the important collections of Niccolò Leonico Tomeo and Pietro Bembo in Padua.[6] During Antico’s and Riccio’s lifetimes, their statuettes enjoyed the same classical authority as genuine antiquities and in later decades were confused with them. These circumstances endowed a hybrid pastiche like the Goddess with a powerful aura of classical credibility. However, the anonymous sculptor of this bronze also proved to be surprisingly inventive in his efforts to convey his ancient subject. His figure, more frontal than Antico’s, evokes the dignified posture of a deity; her outsized ornate diadem signifies she is a goddess; and the blossoms that she holds are probably attributes identifying her as Flora, goddess of flowers and springtime.

The unknown sculptor’s emphasis on clarity, specificity, and ease of apprehension depart from the often poetic ambiguity of Antico and the recondite antiquarianism of Riccio. Our Goddess aligns instead with the developing impulse toward classifying classical imagery expressed, for example, in Vincenzo Cartari’s groundbreaking mythological compendium, Le imagini con la spositione de i dei de gli antichi (Images Depicting the Gods of the Ancients), first published in 1556 in Venice. Intended for a general audience, the book was written in vernacular Italian rather than scholarly Latin, and even its earliest unillustrated editions were best-sellers.[7] Modest bronzes like the Goddess, which were produced in large numbers for the affordable end of the collecting market and designed in a novel colloquially classical mode, anticipated and may even have informed Cartari and later writers’ popularization of the ancient visual world.

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See Allison 1993–94, pp. 183–200, for the history of the replication of Antico’s Nymph and catalogue entries on all known versions.

2. See Luciano 2011, p. 7.

3. The statuette is a brass alloy with round, symmetrically placed, heavy wire core pins, most of which were replaced with copper alloy pins of square section driven into round holes, and a core that appears to have been clay, all features generally consistent with Paduan facture. R. Stone/TR, September 23, 2011.

4. For the possible origins of this type of head in the Seated Woman of ca. 1480–90 in the Wallace Collection (S72) by Giovanni Fonduli da Crema, who may have been Riccio’s teacher, see Warren 2016, vol. 1, pp. 190–201, no. 48. For the transmission of this head type through Riccio and his followers’ workshops, see most recently Wengraf 2018, pp. 8–15, cat. 1.

5. See Motture 2008, pp. 66–67.

6. Michiel 1888, p. 16: “in casa de M. Leonico Thomeo Phylosopho . . . Lo Giove piccolo di bronzo che siede, alla guisa del Giove del Bembo, ma minore, è opera anticha”; pp. 20, 22: “In casa di Misser Pietro Bembo . . . Il Giove picolo dibronzo che siede è opera anticha.”

7. For the publication history of Cartari’s Imagini, see https://bivio.signum.sns.it/html/editions/it/EdInfoCartari_Imagini_Dei.xml.

Artwork Details

- Title:Seated goddess holding flowers (Flora?)

- Date:1550–75

- Culture:Northern Italian

- Medium:Bronze

- Dimensions:Overall (confirmed): 9 7/8 × 4 5/8 × 3 1/8 in. (25.1 × 11.7 × 7.9 cm)

- Classification:Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line:Gift of Mrs. Howard J. Sachs and Mr. Peter G. Sachs, in memory of Miss Edith L. Sachs, 1978

- Object Number:1978.516.4

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.