Automaton in the form of a chariot pushed by a Chinese attendant and set with a clock

During the course of King George III’s (1738–1820) embassy to the Chinese emperor in 1792, the British emissary to China, Lord George Macartney (1737–1806), is reported to have viewed about forty or fifty buildings in the imperial establishment in Beijing that contained “every kind of European toys and sing-songs; with spheres, orreries, clocks, and musical automatons of . . . exquisite workmanship.”[1] Lord Macartney was undoubtedly commenting on the fabled collection of clocks inherited, acquired, and commissioned by Emperor Qianlong (1711–1799). Among these European toys (or singsongs, as the Chinese are believed to have called them), there must have been a pair of automata that had been presented to the Chinese emperor by the English East India Company (1600–1708). The automata were earlier described in the December 1766 edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine:

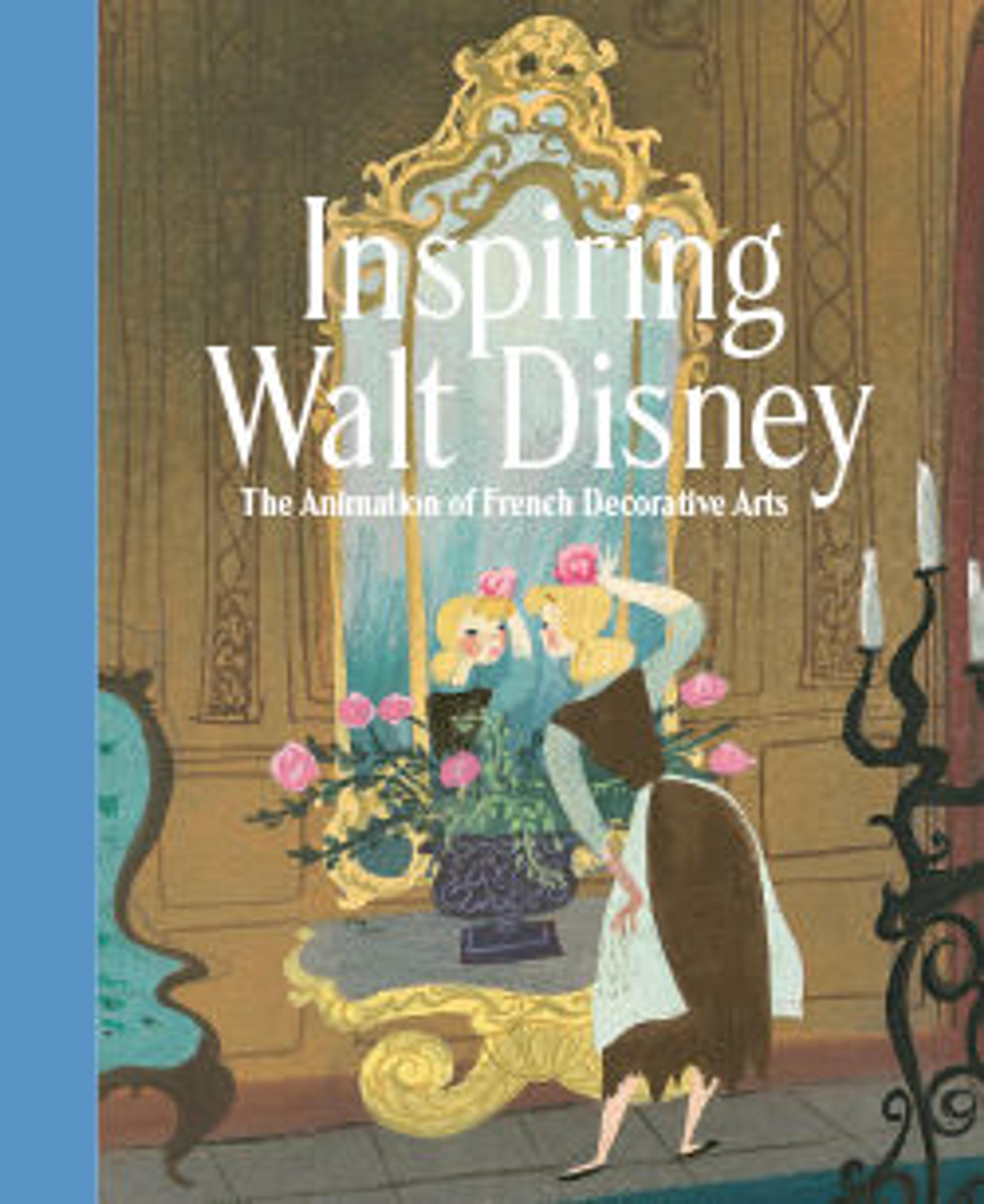

These clocks are in [the] form of chariots, in which are placed, in a fine attitude, a lady leaning her right hand upon a part of the chariot, under which is a clock of curious workmanship, little larger than a shilling, that strikes and repeats, and goes eight days. Upon her finger sits a bird, finely modelled, and set with diamonds and rubies, with its wings expanded in a flying posture, and actually flutters for a considerable time, on touching a diamond button below it; the body of the bird (which contains part of the wheels that in a manner give life to it) is not the bigness of the sixteenth part of an inch.

The lady holds in her left hand a gold tube, not much thicker than a large pin, on the top of which is a small round box, to which a circular ornament set with diamonds, not larger than a sixpence, is fixed, which goes round near three hours in a constant, regular motion. Over the lady’s head (supported by a small fluted pillar, no bigger than a quill) is a double umbrella, under the largest of which a bell is fixed, at a considerable distance from the clock, and seems to have no connection with it, but from which a communication is secretly conveyed to a hammer, that regularly strikes the hour, and repeats the same at pleasure, by touching a diamond button fixed to the clock below.[2]

The Gentleman’s Magazine continues with the description of two birds on spiral springs, which were attached to the front end of the chariot but are now missing from the Museum’s automaton. The article also describes the boy who appears to be pushing the chariot from behind, and the bejeweled flowers atop the parasol that is crowned by a flying dragon. Notwithstanding the omission of the fact that the entire mechanism is propelled by a spring and fusee device and housed above the two central wheels of the chariot, Gentleman’s Magazine provides a nearly exact description of the Museum’s automaton, as recognized by the late Metropolitan Museum curator Clare Le Corbeiller in her catalogue entry for the object in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1984).[3]

It may be noted that the date of the East India Company’s gift in 1766 corresponds to the same year in which the company’s monopoly on British trade to China expired. Presumably, the company hoped that this pair of automata, with its mandarins and flying dragons (European stereotypes of Chinese culture during the Qianlong era), might so delight the emperor that he would be disposed to welcome further British trade.

On a trade card bearing the London address “at the Golden Urn,” from about the middle of the eighteenth century, James Cox proclaimed himself a goldsmith who “Makes Great Variety of Curious Work in Gold, Silver, and other Mettals. Also in Amber, Pearl, Tortoisshell and Curious Stones.”[4] Yet Cox seems to have spent most of his career as an entrepreneur and in 1773, he was said to have “invented sundry pieces of uncommon and expensive workmanship, in the construction of which, employment had been afforded to numbers of ingenious artists and workmen. . . .”[5] Most of the craftsmen were part of a unique network of independent suppliers and craftsmen who resided in London during the second half of the eighteenth century.[6] These craftsmen rarely signed their work, and only a few of them have thus far been identified; nonetheless, their existence made possible the great variety of objects that Cox exported.

The clockmaker’s name was required by law to be visible on watches with enameled dials that were made in London for export, a circumstance that explains the presence of Cox’s name on the dials of watches and clocks that are incorporated into these objects. Cox would have had to depend upon skilled craftsmen in the watchmaking trade, because there is no evidence that he at any time made a watch movement. Beginning in the mid-1760s, Cox produced lavishly ornamented articles for trade with the Far East, first with India and then with China, where his toys were initially well received.[7] A later ban on shipment of his luxury goods to China, however, resulted in the establishment of the shortlived Spring Gardens Museum in London in 1772 and the publication of A Descriptive Catalogue of the Several Superb and Magnificent Pieces of Mechanism and Jewellery, Exhibited in Mr. Cox’s Museum in several editions. In 1775, Cox disposed of his museum’s contents by lottery.

The most spectacular survival of Cox’s enterprise remains the ten-foot-high Peacock Clock in the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, with its clockwork-driven automata, which was brought to the city in 1781, probably by one of Cox’s clockmaker-suppliers, Frederick Jury.[8] Cox hoped to establish direct trade relations with Russia and attempted to sell jewelry to Catherine II, Empress of Russia (Catherine the Great) (1729–1796), although without success.

Cox’s loss of reliable trade with China, the failure in Russia, and the fact that he never achieved royal patronage, in addition to suffering from the ill effects of the American Revolution (1775–83) on British foreign trade, together precipitated his second bankruptcy in 1778. The remaining stock from Canton, China, was sold at Christie’s in London on February 16, 1792. In the meantime, Cox and his sons (one in Canton and the other in London) resumed business and began sending watches, mostly made by the Swiss firm of Jaquet-Droz et Leschot, to China.[9]

The emperor’s second Automaton in the Form of a Chariot is not known to have survived, but the Metropolitan Museum’s example has been traced to a publication titled A Short Account of the Remarkable Clock Made by James Cox, in the Year 1766 . . . for the Emperor of China (1868).[10] It next appeared in the collection of Alfred Charles de Rothschild,[11] and finally, in the collection of Jack and Belle Linsky in New York.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] George Macartney, quoted in Pagani 2001, p. 83. See also Landes 1983, pp. 48–49.

[2] “Description of Two Curious Clocks” 1766. The description was repeated verbatim in Annual Register . . . for the Year 1766 1785, pp. 230–31.

[3] Clare Le Corbeiller in Metropolitan Museum of Art 1984, p. 191, no. 111.

[4] The card is illustrated in R. Smith 2000, p. 353, fig. 16.

[5] See “The Act for Enabling Mr. Cox to Dispose of His Museum by Way of Lottery,” in Descriptive Inventory . . . of Mechanism and Jewellery 1773, p. ii.

[6] For further discussion of these suppliers or subcontractors, especially to the furniture, coachmaking, and scientific instrument trades in eighteenth-century London, see Riello 2008, pp. 257–72.

[7] See Pagani 2001, pp. 102–4. For the automata and clocks signed by Cox that are still in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, see Harcourt-Smith 1933, pp. 13–18; Clocks and Watches of the Qing Dynasty 2002, nos. 51–57.

[8] Zek and R. Smith 2005.

[9] R. Smith 2000; Pagani 2001, pp. 105–9, 112–22. See also 58.75.127 in this volume.

[10] Short Account of the Remarkable Clock 1868. Le Corbeiller in Metropolitan Museum of Art 1984, p. 191, no. 111, noted that the automaton had been acquired in Paris, recounting the story that it had been brought from China by a French sailor, after the looting of the Imperial Summer Palace near Beijing.

[11] C. Davis 1884, vol. 2, no. 141

These clocks are in [the] form of chariots, in which are placed, in a fine attitude, a lady leaning her right hand upon a part of the chariot, under which is a clock of curious workmanship, little larger than a shilling, that strikes and repeats, and goes eight days. Upon her finger sits a bird, finely modelled, and set with diamonds and rubies, with its wings expanded in a flying posture, and actually flutters for a considerable time, on touching a diamond button below it; the body of the bird (which contains part of the wheels that in a manner give life to it) is not the bigness of the sixteenth part of an inch.

The lady holds in her left hand a gold tube, not much thicker than a large pin, on the top of which is a small round box, to which a circular ornament set with diamonds, not larger than a sixpence, is fixed, which goes round near three hours in a constant, regular motion. Over the lady’s head (supported by a small fluted pillar, no bigger than a quill) is a double umbrella, under the largest of which a bell is fixed, at a considerable distance from the clock, and seems to have no connection with it, but from which a communication is secretly conveyed to a hammer, that regularly strikes the hour, and repeats the same at pleasure, by touching a diamond button fixed to the clock below.[2]

The Gentleman’s Magazine continues with the description of two birds on spiral springs, which were attached to the front end of the chariot but are now missing from the Museum’s automaton. The article also describes the boy who appears to be pushing the chariot from behind, and the bejeweled flowers atop the parasol that is crowned by a flying dragon. Notwithstanding the omission of the fact that the entire mechanism is propelled by a spring and fusee device and housed above the two central wheels of the chariot, Gentleman’s Magazine provides a nearly exact description of the Museum’s automaton, as recognized by the late Metropolitan Museum curator Clare Le Corbeiller in her catalogue entry for the object in The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1984).[3]

It may be noted that the date of the East India Company’s gift in 1766 corresponds to the same year in which the company’s monopoly on British trade to China expired. Presumably, the company hoped that this pair of automata, with its mandarins and flying dragons (European stereotypes of Chinese culture during the Qianlong era), might so delight the emperor that he would be disposed to welcome further British trade.

On a trade card bearing the London address “at the Golden Urn,” from about the middle of the eighteenth century, James Cox proclaimed himself a goldsmith who “Makes Great Variety of Curious Work in Gold, Silver, and other Mettals. Also in Amber, Pearl, Tortoisshell and Curious Stones.”[4] Yet Cox seems to have spent most of his career as an entrepreneur and in 1773, he was said to have “invented sundry pieces of uncommon and expensive workmanship, in the construction of which, employment had been afforded to numbers of ingenious artists and workmen. . . .”[5] Most of the craftsmen were part of a unique network of independent suppliers and craftsmen who resided in London during the second half of the eighteenth century.[6] These craftsmen rarely signed their work, and only a few of them have thus far been identified; nonetheless, their existence made possible the great variety of objects that Cox exported.

The clockmaker’s name was required by law to be visible on watches with enameled dials that were made in London for export, a circumstance that explains the presence of Cox’s name on the dials of watches and clocks that are incorporated into these objects. Cox would have had to depend upon skilled craftsmen in the watchmaking trade, because there is no evidence that he at any time made a watch movement. Beginning in the mid-1760s, Cox produced lavishly ornamented articles for trade with the Far East, first with India and then with China, where his toys were initially well received.[7] A later ban on shipment of his luxury goods to China, however, resulted in the establishment of the shortlived Spring Gardens Museum in London in 1772 and the publication of A Descriptive Catalogue of the Several Superb and Magnificent Pieces of Mechanism and Jewellery, Exhibited in Mr. Cox’s Museum in several editions. In 1775, Cox disposed of his museum’s contents by lottery.

The most spectacular survival of Cox’s enterprise remains the ten-foot-high Peacock Clock in the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, with its clockwork-driven automata, which was brought to the city in 1781, probably by one of Cox’s clockmaker-suppliers, Frederick Jury.[8] Cox hoped to establish direct trade relations with Russia and attempted to sell jewelry to Catherine II, Empress of Russia (Catherine the Great) (1729–1796), although without success.

Cox’s loss of reliable trade with China, the failure in Russia, and the fact that he never achieved royal patronage, in addition to suffering from the ill effects of the American Revolution (1775–83) on British foreign trade, together precipitated his second bankruptcy in 1778. The remaining stock from Canton, China, was sold at Christie’s in London on February 16, 1792. In the meantime, Cox and his sons (one in Canton and the other in London) resumed business and began sending watches, mostly made by the Swiss firm of Jaquet-Droz et Leschot, to China.[9]

The emperor’s second Automaton in the Form of a Chariot is not known to have survived, but the Metropolitan Museum’s example has been traced to a publication titled A Short Account of the Remarkable Clock Made by James Cox, in the Year 1766 . . . for the Emperor of China (1868).[10] It next appeared in the collection of Alfred Charles de Rothschild,[11] and finally, in the collection of Jack and Belle Linsky in New York.

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] George Macartney, quoted in Pagani 2001, p. 83. See also Landes 1983, pp. 48–49.

[2] “Description of Two Curious Clocks” 1766. The description was repeated verbatim in Annual Register . . . for the Year 1766 1785, pp. 230–31.

[3] Clare Le Corbeiller in Metropolitan Museum of Art 1984, p. 191, no. 111.

[4] The card is illustrated in R. Smith 2000, p. 353, fig. 16.

[5] See “The Act for Enabling Mr. Cox to Dispose of His Museum by Way of Lottery,” in Descriptive Inventory . . . of Mechanism and Jewellery 1773, p. ii.

[6] For further discussion of these suppliers or subcontractors, especially to the furniture, coachmaking, and scientific instrument trades in eighteenth-century London, see Riello 2008, pp. 257–72.

[7] See Pagani 2001, pp. 102–4. For the automata and clocks signed by Cox that are still in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, see Harcourt-Smith 1933, pp. 13–18; Clocks and Watches of the Qing Dynasty 2002, nos. 51–57.

[8] Zek and R. Smith 2005.

[9] R. Smith 2000; Pagani 2001, pp. 105–9, 112–22. See also 58.75.127 in this volume.

[10] Short Account of the Remarkable Clock 1868. Le Corbeiller in Metropolitan Museum of Art 1984, p. 191, no. 111, noted that the automaton had been acquired in Paris, recounting the story that it had been brought from China by a French sailor, after the looting of the Imperial Summer Palace near Beijing.

[11] C. Davis 1884, vol. 2, no. 141

Artwork Details

- Title: Automaton in the form of a chariot pushed by a Chinese attendant and set with a clock

- Maker: James Cox (British, ca. 1723–1800)

- Date: 1766

- Culture: British, London

- Medium: Case: gold with diamonds and paste jewels set in silver, pearls; Dial: white enamel; Movement: partly gilded brass and steel, wheel balance and cock of silver set with paste jewels

- Dimensions: Overall: 10 1/4 × 6 3/8 × 3 1/4 in. (26 × 16.2 × 8.3 cm)

- Classification: Metalwork-Gold and Platinum

- Credit Line: The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982

- Object Number: 1982.60.137

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.