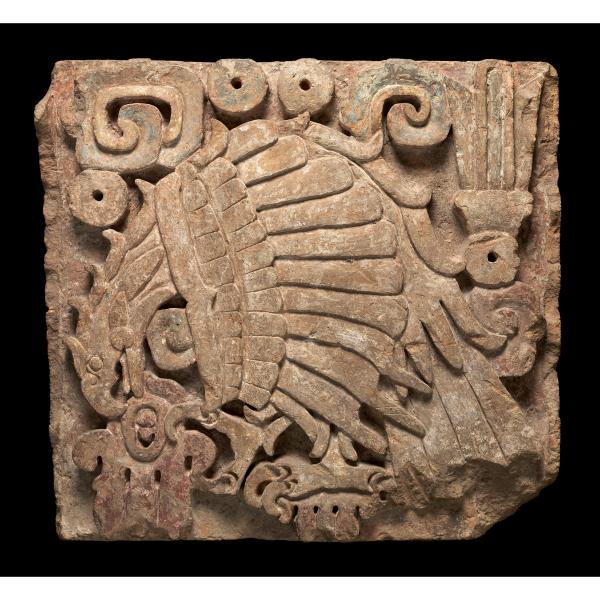

Eagle relief

The Eagle Panels are among the finest examples of Mesoamerican stone relief sculpture, highly sophisticated in both composition and technique. In each, the curve of the bird’s back, from its head through its tail feathers, forms an arc that determines the entire composition and nearly fills the frame. The artist has placed glyph-like scrolls, shells, pierced circles (chalchihuitl), and what appears to be a bundle of reeds or a stylized ear of maize in the remaining spaces. A narrow, raised band once framed the image, and the remaining fragments can be seen on either side. The ends of the tail feathers and the bottom right corner of this panel have broken off. Traces of paint remain on the background and inner carved surfaces, and intervening layers of plaster were discovered during conservation, indicating that the panels had been repainted multiple times, a testament to their importance. The sculptor employed a highly refined carving technique to create a multi-leveled composition, and to maximize the effect of light and shadow. Each row of feathers, from the eagle’s tail through its neck, is rendered in a slightly higher level of relief, and each of the primary (flight) feathers is cut at an angle, so that they appear to overlap, suggesting even greater depth. The outer edges of the scrolls similarly bevel back, creating deep shadows.

When he purchased the panels, Frederic Church, an early trustee of the museum, was told that they had been found by a farmer plowing his field in northern Veracruz, near the city of Tampico, a region dominated by the Huastecs at the time of the conquest. However, the panels are unlike any known examples of stone carving from the area. Instead, they reflect a cosmopolitan blend of artistic traditions found in several regions of Mesoamerica. Most similar are the stone relief panels which adorn the outer walls of sacred structures at Tula in central Mexico, El Cerrito, Queretaro, and Chichén Itzá on the Yucatan Peninsula, although these are much cruder in execution, and simpler in design. These regions had contact with Veracruz via trade routes across both land and sea, making it possible that the iconography of the panels, or the panels themselves, may have originated elsewhere in Mesoamerica.

Eagles loomed large in myth and imagery throughout ancient Mesoamerica, representing both worldly strength and spiritual power. According to Mexica (Aztec) mythology, eagles, soaring high into the sky, are symbols of the sun crossing the heavens. The sun itself needs strength to survive the dangerous nightly journey through the darkness of the underworld, and then to rise again each morning, allowing life on earth to continue. It is the obligation of human beings, through sacrificial offerings, to provide nourishment for the journey. Sacrifice, of the ruler or priest’s own blood, or of the blood, hearts, and lives of victims, was practiced throughout Mesoamerica, and is frequently depicted in sculpture, painting, and codices.

In describing the Mexica practice of human heart sacrifice, the early Spanish chronicler, Friar Bernardino de Sahagún, wrote that, after pulling it from the chest of the victim, the priest placed the sacrificed heart into a cuauhxicalli (eagle vessel). These cuauhxicalli could vary in form, size, and material, and a number have been identified. The Codex Borbonicus, written shortly before or after the Spanish conquest, depicts cuauhxicalli decorated with rows of eagle feathers, stylized hearts, and chalchihuitl, symbols of preciousness also seen on the panels, thus indicating both the nature of their use and the worth of their contents. There are three nearly identical greenstone examples in the collections of the Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C., the Weltmuseum Wien (Vienna), and the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. The Mexica symbol of the Fifth Sun, our present era, is carved into the inner surface of each. The placement of the sacrificial heart there would directly feed the sun and guarantee its return from the underworld, symbolized by the image of the earth deity Tlaltecuhtli carved on the bottom of the vessel. A cuauhxicalli in the Museo del Templo Mayor in Mexico City is in the shape of an over-life-sized stone sculpture of an eagle with a deep, bowl-like depression in its back. Its form most directly reflects its ritual purpose and meaning when, during the ritual, the heart is placed into the depression, into the body of the eagle. On these panels the representation of the eagle’s, or sun’s consuming of the nourishment of the sacrificed heart is more directly represented.

Patricia J. Sarro, 2024

Further Reading

Beyer, Herman. “The So-called ‘Calendario Azteca’: Description of the Cuauhxicalli of the ‘House of the eagles’ (1921)”. In The Aztec Calendar Stone, Khristaan Villela and Mary Ellen Miller, eds., pp. 104-117. Los Angeles: Getty Research Center, 2010.

Braun, Barbara. Precolumbian Art in the Post Columbian World. New York: Abrams, 1993.

Easby, Elizabeth Kennedy, and John F. Scott. Before Cortez: Sculpture in Middle America. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970, no. 253.

González Block, Miguel Ángel. Dos águilas y un sol. Identidad, simbolismo, y conquista del Cuauhtli Sagrado.

Heyden, Doris.”Posibles anticedentes del glifo de México-Tenochtitlan en los códices pictóricos y en la tradícion oral”. In Primer Coloquio de Documentos Pictográficos de Tradición Náhuatl. Carlos Martínez Marín, ed, pp. 229. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1989.

Kowalski, Jeff Karl, and Cynthia Kristin-Graham, eds. Twin Tollans. Cambridge: Dumbarton Oaks and Harvard University Press, 2007.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, and Felipe Solís Olguín. The Aztec Calendar Stone and Other Solar Monuments. Translated by H.J. Drake. Mexico City: Conaculta, Instituto Nacional de Antropoligía y Historia, Grupo Azabache, 2004.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, and Felipe Solís Olguín. El calendario azteca y otros monumentos solares. Mexico City: Conaculta, Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Historia, Grupo Azabache, 2004.

Newton, Douglas, Julie Jones, and Kate Ezra. The Pacific Islands, Africa, and the Americas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

Sahagún, Bernadino, de. General history of the things of New Spain/Florentine Codex. Edited and translated Into English, with notes and illus., by Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble; Santa Fe, N.M., School of American Research, 1950-82. (English and Spanish text).

Sahagún, Bernadino, de. Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España, Book 2. Edited by Alfredo López Austin and Josephína García Quintana. Madrid: Alianza, 1988.

Seler, Eduard, “Collected Works in Mesoamerican Linguistics and Archaeology (1888, 1889, 1901, 1915)”. In The Aztec Calendar Stone, Khristaan Villela and Mary Ellen Miller, eds., pp. 104-117. Los Angeles: Getty Research Center, 2010.

Taube, Karl. The Womb of the World, Cuauhxicalli and Other Offering Bowels of Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica. In Maya Archaeology 1, edited by Charles Golden, Stephen Houston, and Joel Skidmore, pp. 86-106. San Francisco: Precolumbian Mesoamerican Press, 2009.

Turner, Andrew D. and Cynthia Kristan-Graham (2023) “Tula and the Origins and Characteristics of an Epiclassic-Early Postclassic Art Tradition.” In When East Meets West: Chichen Itza, Tula, and the Postclassic Mesoamerican World, vol. 1, Travis W. Stanton, Karl A. Taube, Jeremy D. Coltman, and Nelda I. Marengo Camacho, eds., pp. 417-468. BAR Publishing, Oxford.

Artwork Details

- Title: Eagle relief

- Artist: Toltec artist(s)

- Date: 900–1200 CE

- Geography: Mexico

- Culture: Toltec

- Medium: Andesite or dacite, Maya blue, stucco, red pigment

- Dimensions: H. 27 1/2 × W. 29 1/2 × D. 3 in. (69.9 × 74.9 × 7.6 cm)

- Classification: Stone-Sculpture

- Credit Line: Gift of Frederic E. Church, 1893

- Object Number: 93.27.1

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1639. Eagle reliefs, Toltec artists

Leonardo López Luján

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK (NARRATOR): The eagle motif on these stone reliefs might seem familiar. Similar imagery appears on Mexico's flag, as a tribute to the region's long and extremely rich indigenous cultural history. Leonardo López Luján, archaeologist and director of the Templo Mayor project.

LEONARDO LÓPEZ LUJÁN (English translation): This sculpture belongs to the Toltec civilization. We see a bas-relief of a bird of prey, likely an eagle, clutching two hearts in its claws. These hearts are depicted in the style of Teotihuacan and Tula. The eagle devours one of the hearts.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Tula was the Toltec capital. Panels much like these adorned the outer walls of one of Tula’s sacred structures, and similar reliefs were discovered inside one of the city’s great pyramids. The Toltec civilization thrived in the Mexican highlands from 1000 to 1300 CE. The Mexica people, sometimes called the Aztecs, who built an empire in the region centuries later, may have unearthed and collected this object.

LEONARDO LÓPEZ LUJÁN (English translation): We know the Mexicas and their contemporaries would often visit archeological sites and abandoned cities to carry out their own excavations. They recovered sculptures, paintings and sacred objects from ancient Toltec offerings and tombs. Then, they would take their finds back to Tenochtitlan to rebury them as offerings to their own gods.

Mexica historical sources from the 16th century often reference Toltec history. These sources describe mythical Tula as a magnificent place of fertility, where the inhabitants grew giant tomatoes, pumpkins and corn. The Mexica claimed to be descended from that great civilization and inheritors of a rich tradition of Toltec artisans and craftspeople.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: This panel was among the first Ancient American objects to join The Met's collection. 19th century landscape painter Frederic Church acquired it and presented it to the Museum.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.