Stirrup-spout bottle with deer

This stirrup-spout bottle depicts a deer embracing two fawns as if they were human offspring. Moche artists were highly skilled at depicting realistic images of humans, animals, and plants, but occasionally elements are combined in ways that are distinctly imaginative. Here, the potter carefully represented a white-tailed doe, recognizable by the markings on the creature’s coat. Details of the deer such as the erect ears, antlers, and hooves were modeled and painted using red and white slips (suspensions of clay and/or other colorants in water).

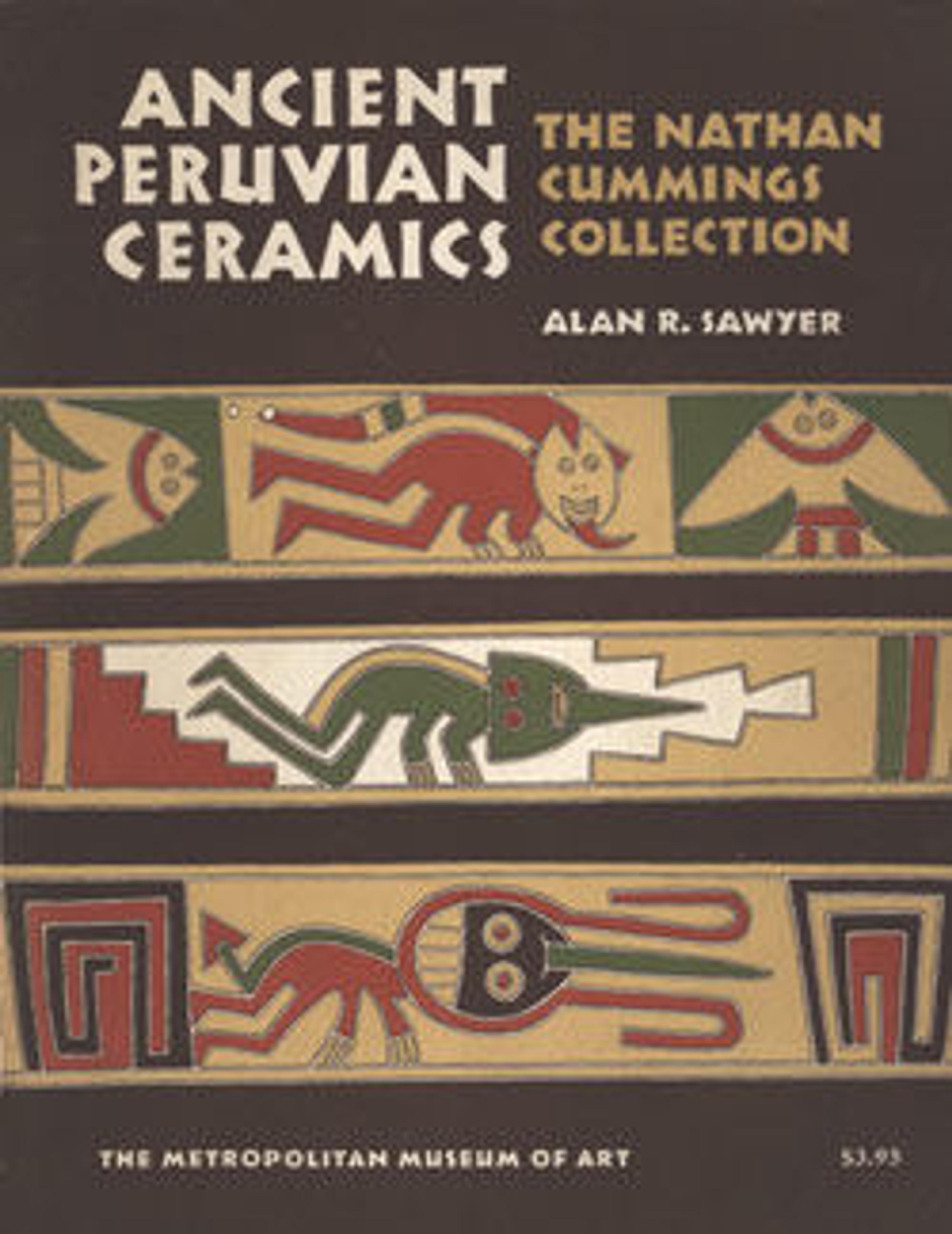

Deer are often represented in Moche ceramics. Scenes of deer hunting are painted on the surfaces of some pots in a style known as fineline (Donnan and McClelland, 1999: 104, fig. 4.54). Modeled representations of seated deer are also known; sometimes they hold lime containers—part of the paraphernalia for chewing coca (see, for example, a work in the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2008.1). Scholars are unsure whether these seated deer represent prey to be consumed or whether deer had special symbolic or metaphorical meanings for Moche viewers.

The stirrup-spout vessel—the shape of the spout recalls the stirrup on a horse's saddle—was a much-favored form on Peru's North Coast for about 2,500 years. Although the importance and symbolism of this distinctive shape is still puzzling to scholars, the double-branch/single-spout configuration may have prevented evaporation of liquids, and/or may have provided a convenient handle. Early in the first millennium CE, the Moche elaborated stirrup-spout bottles into sculptural shapes depicting a wide range of subjects, including human figures, animals, and plants worked with a great deal of naturalism.

The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200–850 CE, centuries before the rise of the Incas. Over the course of some six centuries, the Moche built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although the precise nature of Moche political organization is a subject of debate, these centers shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010).

References and Further Reading

Cordy-Collins, Alana. “The Sacred Deer Complex: Out of Eurasia,” In Adventures in Pre-Columbian Studies: Essays in Honor of Elizabeth P. Benson, edited by Julie Jones, pp. 139-160. Washington D.C.: Pre-Columbian Society of Washington, D.C., 2010.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Deer Hunting and Combat: Parallel Activities in the Moche World.” In The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera, edited by Kathleen Berrin, pp. 51-60. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion.” In New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo, pp. 47-69. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010.

Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland. Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, 1999.

Deer are often represented in Moche ceramics. Scenes of deer hunting are painted on the surfaces of some pots in a style known as fineline (Donnan and McClelland, 1999: 104, fig. 4.54). Modeled representations of seated deer are also known; sometimes they hold lime containers—part of the paraphernalia for chewing coca (see, for example, a work in the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2008.1). Scholars are unsure whether these seated deer represent prey to be consumed or whether deer had special symbolic or metaphorical meanings for Moche viewers.

The stirrup-spout vessel—the shape of the spout recalls the stirrup on a horse's saddle—was a much-favored form on Peru's North Coast for about 2,500 years. Although the importance and symbolism of this distinctive shape is still puzzling to scholars, the double-branch/single-spout configuration may have prevented evaporation of liquids, and/or may have provided a convenient handle. Early in the first millennium CE, the Moche elaborated stirrup-spout bottles into sculptural shapes depicting a wide range of subjects, including human figures, animals, and plants worked with a great deal of naturalism.

The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200–850 CE, centuries before the rise of the Incas. Over the course of some six centuries, the Moche built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although the precise nature of Moche political organization is a subject of debate, these centers shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010).

References and Further Reading

Cordy-Collins, Alana. “The Sacred Deer Complex: Out of Eurasia,” In Adventures in Pre-Columbian Studies: Essays in Honor of Elizabeth P. Benson, edited by Julie Jones, pp. 139-160. Washington D.C.: Pre-Columbian Society of Washington, D.C., 2010.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Deer Hunting and Combat: Parallel Activities in the Moche World.” In The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera, edited by Kathleen Berrin, pp. 51-60. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion.” In New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo, pp. 47-69. Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010.

Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland. Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California, 1999.

Artwork Details

- Title: Stirrup-spout bottle with deer

- Artist: Moche artist(s)

- Date: 500–800 CE

- Geography: Peru

- Culture: Moche

- Medium: Ceramic, slip

- Dimensions: H. 11 × W. 5 1/2 × D. 8 1/2 in. (27.9 × 14 × 21.6 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Containers

- Credit Line: Gift of Nathan Cummings, 1963

- Object Number: 63.226.7

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.