Female Figurine

Not on view

This figurine is hollow and originally was comprised of five pieces of relatively pure silver sheet joined by metallurgical means. Similar to other Inca female figurines in terms of its appearance and design, it depicts a standing woman with hair pulled back and arms drawn to the chest. The figurine was likely deposited as an Inca offering, and may have been dressed in textiles fastened with tupus (pins), whether as part of the ritual practice of capac hucha, or as another form of Inca dedication of/to huacas, sacred beings that included points in the natural landscape (Bray 2009; Cruz 2007). These female anthropomorphic figurines may be fabricated in metal or in the shell Spondylus spp. One such figurine of Spondylus princeps was deposited in an Inca offering in Unit 16, Platform 1 of the Moche site of Huaca de la Luna, where it was wrapped in three separate textiles, an aksu, lliclla, and faja, tied with tupus, two of which are threaded on a cord from which Spondylus plaques hang (Rojas et al. 2012).

While made of different materials, the metal and shell female anthropomorphic figurines tend to indicate the same bodily details in similar designs: textured hair pulled back into two tresses tied at their ends in a rectangular bar or tassel, open, almond-shaped eyes, nose, mouth, ears, breasts, hands drawn close to the chest, and vagina. Across this corpus of Inca anthropomorphic figurines in metal, there are usually three height groups (5-7 cm, 13-15 cm, 22-24 cm) (see McEwan 2015, 282, n. 15), and this figurine is in the middle height group.

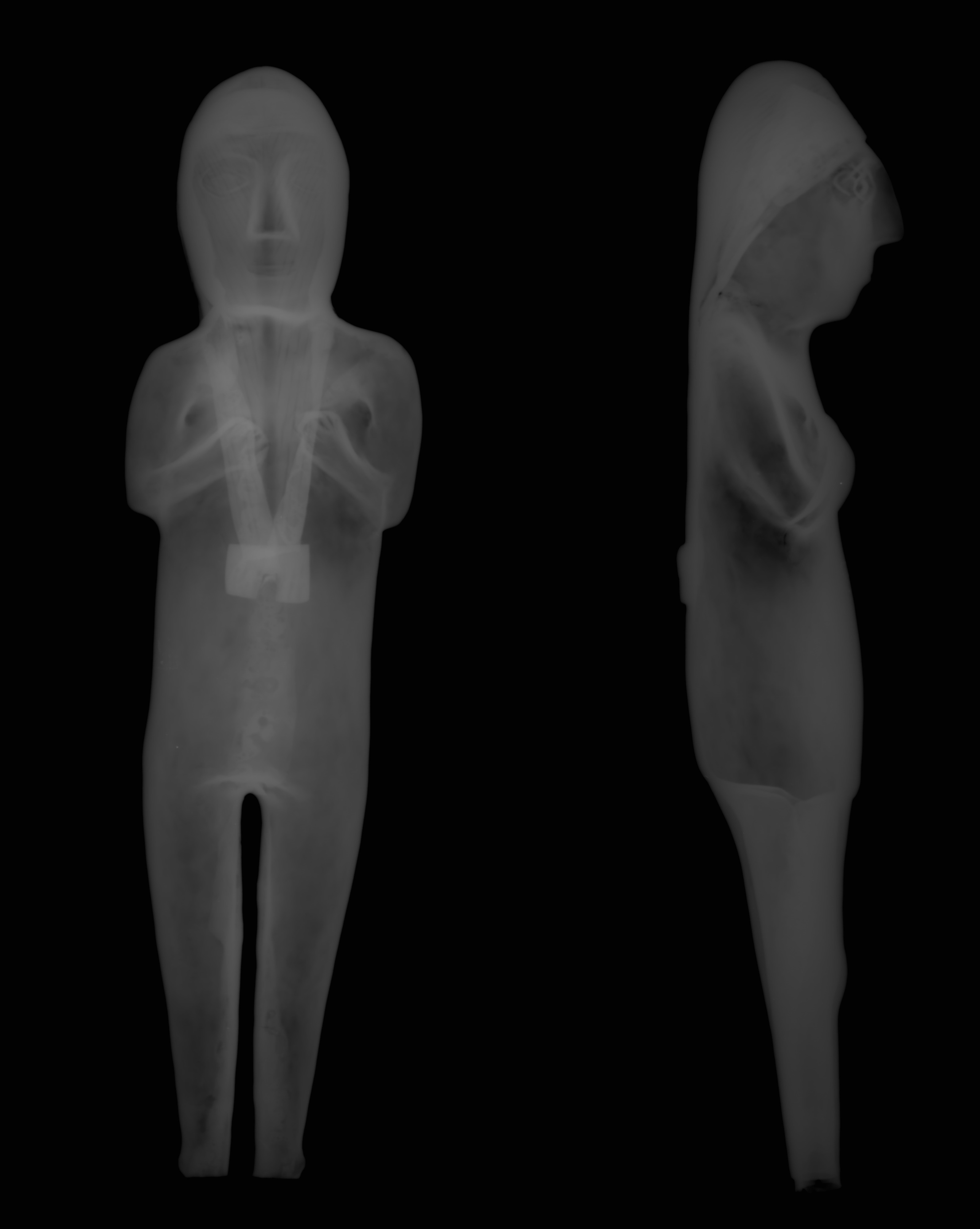

The five sheet components of this figurine are: the hair, the tassel at the end of the hair, the head, torso, and legs all as one piece, and the two individual feet that are now missing. Like 1995.481.5 and other Inca female figurines made of metal, the helmet-like hair section was placed over and soldered to the open top/back of the head during fabrication (see image 4, profile view). In this figure, however, small dents and areas of misshapen metal in the hair—along with a slightly askew positioning of the head (see image 4, profile view)—suggest that the hair was damaged and then re-attached.

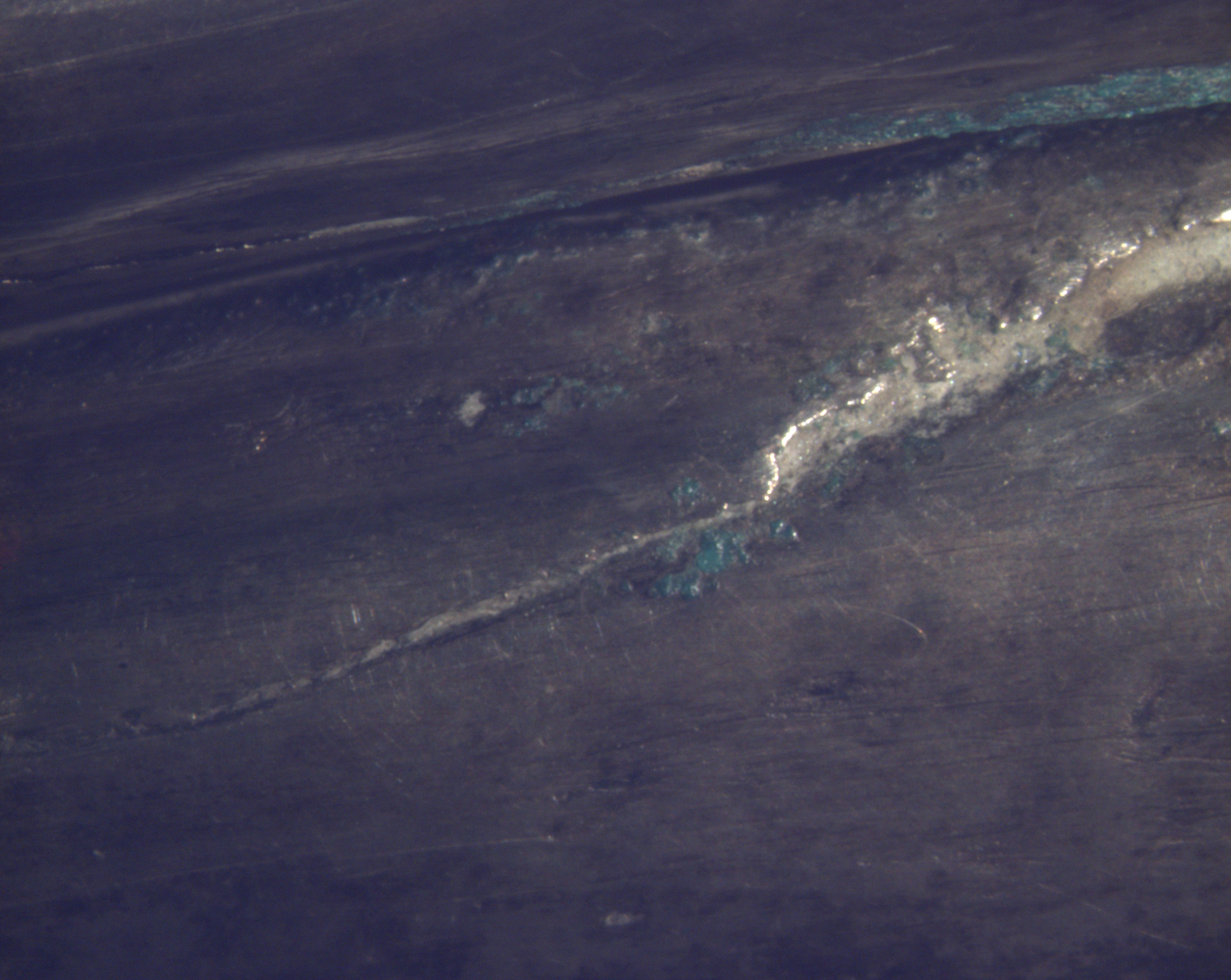

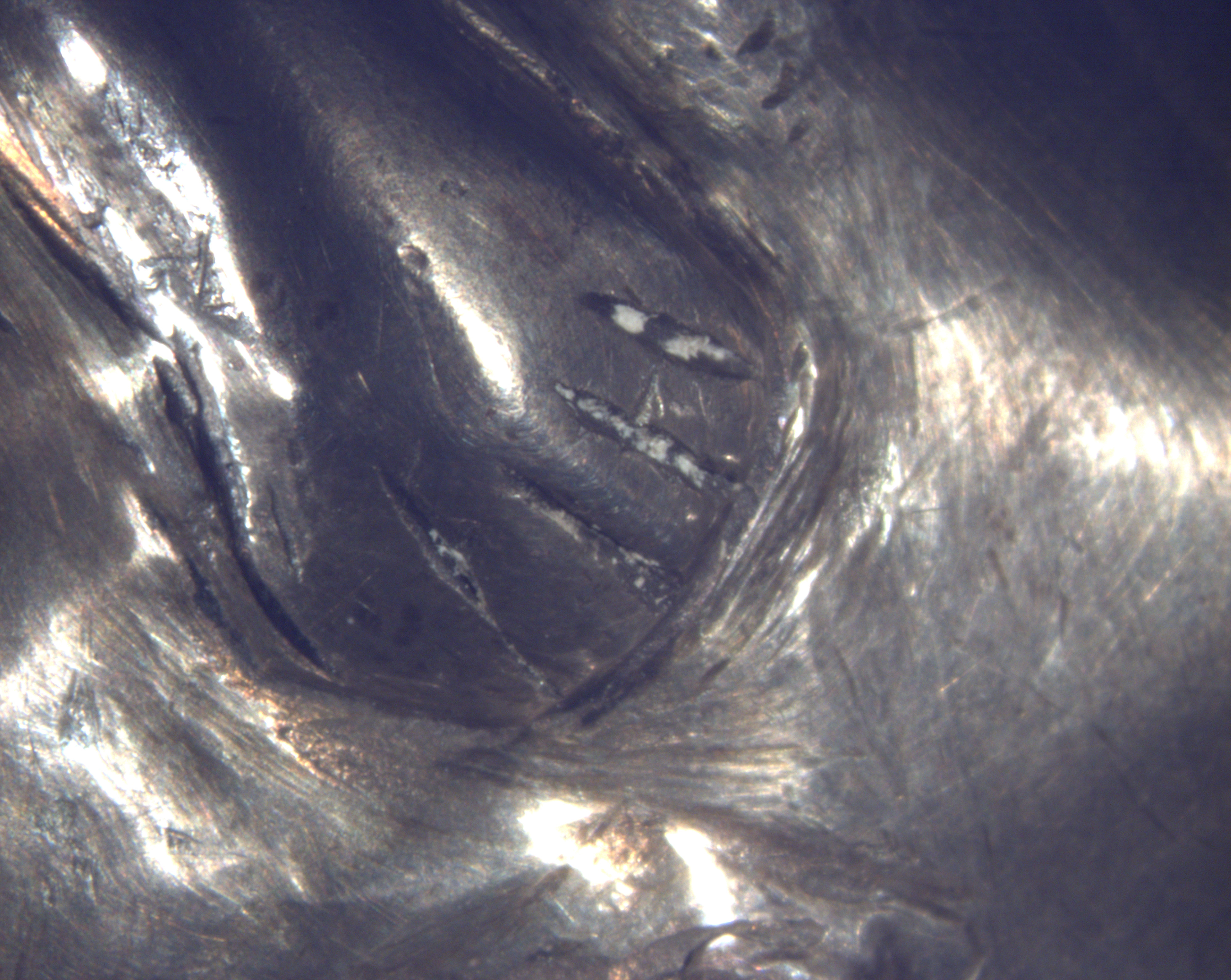

The tresses of hair are shown as tied by a tassel at the back. Usually the tassel is part of the hair piece on Inca female figurines but in this case the hair and tassel were applied separately (see image 5). These tassels may be referred to as simp’anas in Quechua or k’anañas in Aymara and, according to peoples in the Peruvian altiplano, may be made of alpaca wool (Valencia 1981, 57). There is a seam in a zigzag shape down the back (see image 6), where the two ends of the torso sheet would have been joined. X-radiography reveals porosity in the region of the overlap of these ends (see image 4, front-back view), suggesting the use of a solder. Interestingly, unlike many other Inca anthropomorphic figurines (cf. Lechtman 1996), there does not appear to be a gusset of metal in the genital region, a separate piece that would have bridged the torso and leg pieces. Instead, the crotch area is formed by the intersection of the torso and leg pieces. The seam on each leg is diagonal, extending from the interior of each leg onto the more visible back of the leg at the bottom, and there are deposits of metal—likely a solder—in the area of these seams (see image 7).

Comparing metal anthropomorphic and camelid figurines, it is clear that Inca metallurgists thought carefully about feet attachments. On camelid figurine 1998.34 in the Princeton University Art Museum, the feet attachments are partially cylindrical on top so that they extend and fit into the hollow legs (Cockrell and McEwan n.d.). On a female figurine from Isla de la Plata, 4450 in the Field Museum, interior pins have been applied to secure the feet to the legs (Cockrell et al. n.d.). On 1979.206.336, the feet are missing but there are areas of solidified metal (solder?) on the ankles, near where the feet would have been located (see image 8). This suggests that the feet, now missing, were originally fitted over the legs, rather than fitted into them, with the use of solder.

The hair has been engraved to show its texture and includes a central line that more or less divides the hair in half (see image 9). Like other figurines, there is a hammered, vertical, relatively narrow depression or concave fold down the back of the hair whose purpose is unknown. The facial details have been created by working both sides of the sheet that now forms the head. The hands were formed by hammering, and the fingers on the hands have been delineated by engraving (see image 10). The figure’s breasts are indicated by slight raised circles, and its vagina has been indicated by hammering a small V-shaped indentation. This tassel is marked with only one row of engraved design unlike figurine 1995.481.5, for instance, which shows two rows.

The x-ray (see image 4, profile view) reveals a slight separation (dark contrast) at the side of the neck region, confirming that, at some time, there was probably a failure of the hair and head/neck join, resulting in the separation or disattachment of the two sections. Combined with the post-casting addition of metal in the neck immediately below the proper right jaw, it is likely that damage was extensive in this area. The repair, which probably included the re-soldering of the hair to the head, likely accounts for the slightly askew position of the hair on top of the head noted earlier. Areas of green copper corrosion on the backside of the figurine are from areas of solder employed in fabrication and/or repair and re-heating procedures. This figurine was cleaned by conservators in October 1957 and January 1971.

Technical notes: Optical microscopy, X-radiography, and XRF conducted in 2017.

Bryan Cockrell, Curatorial Fellow, AAOA

Beth Edelstein, Associate Conservator, OCD

Ellen Howe, Conservator Emerita, OCD

Caitlin Mahony, Assistant Conservator, OCD

2017

References

Bray, Tamara. “An Archaeological Perspective on the Andean Concept of Camaquen: Thinking Through Late Pre-Columbian Ofrendas and Huacas.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19, no. 3 (2009): 357-366.

Cockrell, Bryan, and Colin McEwan. “The Fabrication and Ritual Significance of Inca Miniature Figurines in PUAM.” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, forthcoming.

Cockrell, Bryan, McEwan, Colin, Williams, Patrick Ryan, and Laure Dussubieux. “The Ritualized Production of an Inca Assemblage from Isla de la Plata, Ecuador”. Unpublished manuscript.

Cruz, Pablo J. “Huacas olvidadas y cerros santos: Apuntes metodológicos sobre la cartografía sagrada en los Andes del sur de Bolivia.” Estudios Atacameños (San Pedro de Atacama) 38 (2009): 55-74.

Lechtman, Heather. “Technical Descriptions,” in Andean Art at Dumbarton Oaks, edited by Elizabeth Hill Boone. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996.

McEwan, Colin. "Ordering the Sacred and Recreating Cuzco," in The Archaeology of Wak'as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, edited by Tamara L. Bray, 265-291. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Rojas, Carol, Moisés Tufinio, Ronny Vega, and Mirtha Rivera. “Unidad 16 - Plataforma I de Huaca de la Luna.” In Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna: Informe técnico 2011, edited by Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, 75-127. Trujillo: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Trujillo, 2012.

Valencia Espinoza, Abraham. Metalurgia Inka: Los ídolos antropomorfos y su simbología. Cusco, 1981.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.