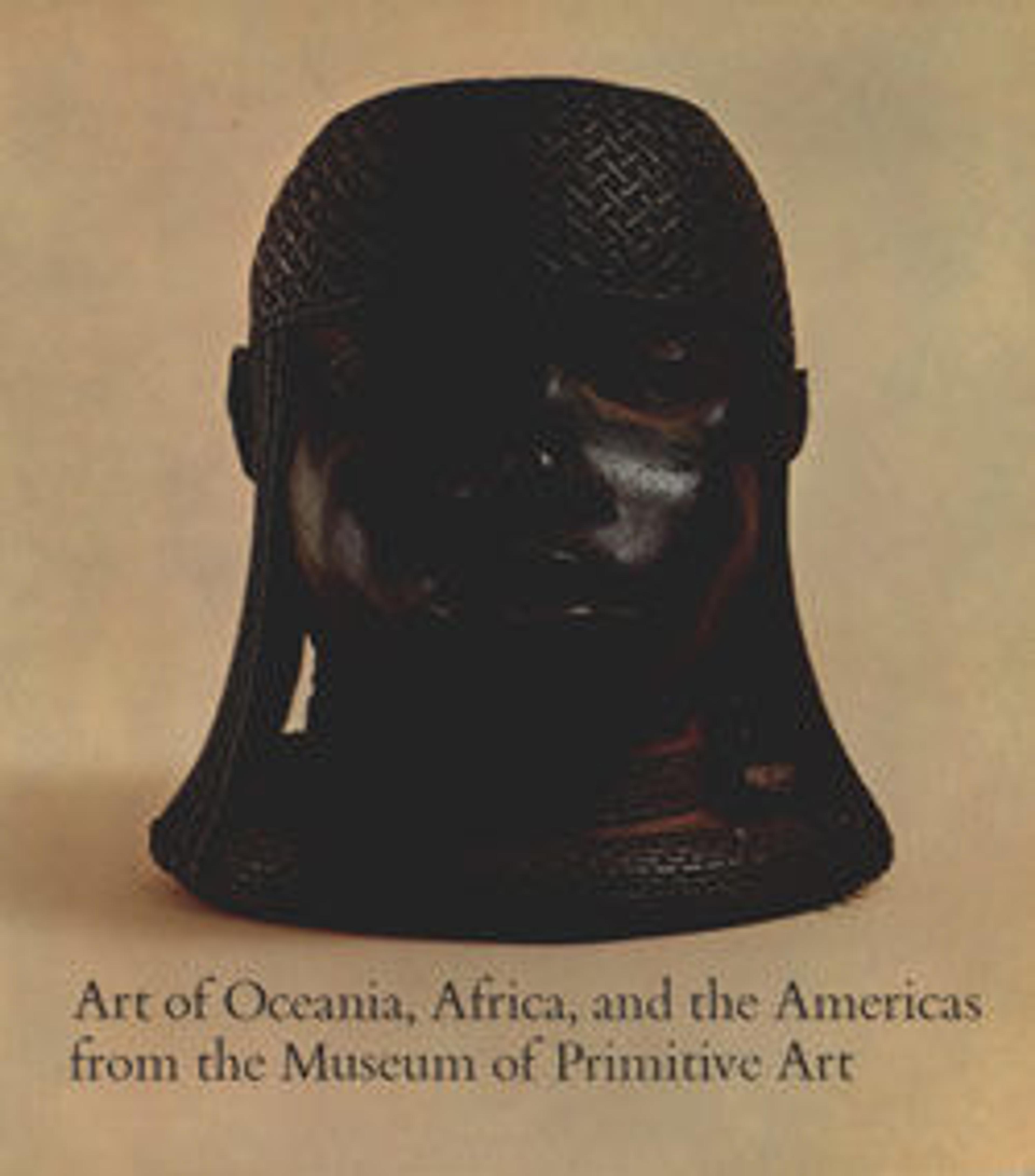

Standing male figure

The dry conditions of Peru’s coastal desert allows for the preservation of organic materials such as wood and cloth—materials that in most other parts of the Americas would not have survived centuries exposed to the elements or buried in the ground. This standing male figure, now missing its lower legs, wears a flat-topped conical headdress and large round ear ornaments. Below a strong browline are oval-shaped eyes, a prominent nose, a small oval-shaped mouth, and lines indicating nasolabial folds. He wears a wide loincloth and holds a tall, cylindrical object between his hands. Its tapered shape suggests that it represents a type of beaker known from Peru’s North Coast (see, for example, MMA 1978.412.183, .185).* Particularly ornate versions of these tall vessels, made of silver and gold, have been found at Chan Chan, capital of the Chimú kingdom (Pillsbury, Potts, and Richter, 2017:cat. 72; Ríos and Retamozo 1982). These drinking vessels would have been used in ritual feasts that were at the heart of Andean statecraft.

The figure’s loincloth wraps around the body, and at the back, its curved lower edge extends to the upper thighs. Seen from behind, the slightly pointed shape of the figure’s ears is more pronounced. This ear shape is associated with depictions of figures from Lambayeque, a northern region the Chimú conquered in the fourteenth century. Heavily weathered, the figure was likely once painted.

Such wood sculptures were installed at entrances to buildings and tombs on the North Coast. Most notably, sculptures of the scale of the present example stood as sentries in entryways of the palaces of Chan Chan. This vast adobe city, the remains of which can still be seen outside of the modern city of Trujillo, thrived between ca. 1000 and 1470 CE, when it fell to the invading Inca army. Chan Chan encompasses some 8 square miles (20 km2), and is dominated by ten royal compounds with high perimeter walls thought to be the palaces, administrative centers, and, ultimately, funerary structures of the Chimú kings. The compounds contained grand open courtyards, walk-in wells, and ample storage facilities. Sixteenth-century accounts of the looting of these palaces describe the immense quantities of gold and silver that were found within their walls. Perhaps because of their contents, but also likely for social and political reasons, security was clearly a concern at Chan Chan and access was highly restricted. The compounds had a single entrance, on the north perimeter wall, and progress through the palaces was impeded by a system of baffled entries, further controlling the flow of visitors. Wooden guardians such as the present example were surely part of a complex system designed to protect the exclusive and sacred spaces of the Chimú elite and to celebrate eternally the rituals held within them. Similar, usually smaller, wood sculptures were also part of free-standing processional tableaux and architectural models deposited in burials (see, for example, Jackson, 2004; Uceda, 1999, 2011), perhaps for related purposes.

*It is also possible, however, that the object the figure grasps represents a type of flute known as a quena. Matthew Helmer excavated two similar, but slightly smaller wood sculptures in a Chimú-Inca period burial at Samanco, in the Nepeña Valley (Helmer 2015:fig. 4.22). Helmer interprets the somewhat longer and thinner cylindrical objects on the Nepeña sculptures as flutes, and for good reason, as the tomb contained some 16 actual cane flutes. Given the shorter, wider proportions of the present example, however, and the taper of the top and bottom, the form more closely resembles the characteristic drinking vessels from Chornancap, a Lambayeque site (Wester La Torre, 2016:315, fig. 197), and a set of Chimú silver vessels reportedly from the Chicama Valley (including MMA 1978.412.181, .183, .185, .186).

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of Ancient American Art, 2018

References and Further Reading

Campana Delgado, Cristóbal. Chan Chan del Chimo. Lima: Editorial Orus, 2006.

Cummins, Thomas B.F. Toasts with the Inca; Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Helmer, Matthew. The Archaeology of an Ancient Seaside Town: Performance and Community at Samanco, Nepeña Valley, Peru (ca. 500-1 BC). Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015.

Jackson, Margaret. “The Chimú Sculptures of Huacas Tacaynamo and El Dragon, Moche Valley, Peru.” Latin American Antiquity vol. 15, No. 3 (2004), pp. 298-322.

Pillsbury, Joanne. “Imperial Radiance: Luxury Arts of the Incas and their Predecessors,” in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim Richter, pp. 33-43. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.

“Reading Art without Writing: Interpreting Chimú Architectural Sculpture,” in Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century, Elizabeth Cropper, ed., pp. 72-89. Studies in the History of Art 74, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Symposium Papers LI. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, Distributed by Yale University Press, 2009.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017).

Pillsbury, Joanne, Patricia Sarro, James Doyle, and Juliet Wiersema. Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Ríos, Marcela, and Enrique Retamozo. 1982. Vasos ceremoniales de Chan Chan. Lima: ICPNA, 1982.

Uceda, Santiago. “Esculturas en miniatura y una maqueta en madera: El culto a los muertos y a los ancestros en la época Chimú,” Beiträge zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 19 (1999), pp. 259-311.

Uceda, Santiago. “Las maquetas Chimú de las Huacas de la Luna y sus contextos,” in Modelando el mundo: Imágenes de la arquitectura precolombina, ed. Cecilia Pardo, pp. 144-163. Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2011.

Wester La Torre, Carlos. Chornancap: Palacio de una gobernante y sacerdotisa de la cultura Lambayeque. Chiclayo: Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, 2016.

The figure’s loincloth wraps around the body, and at the back, its curved lower edge extends to the upper thighs. Seen from behind, the slightly pointed shape of the figure’s ears is more pronounced. This ear shape is associated with depictions of figures from Lambayeque, a northern region the Chimú conquered in the fourteenth century. Heavily weathered, the figure was likely once painted.

Such wood sculptures were installed at entrances to buildings and tombs on the North Coast. Most notably, sculptures of the scale of the present example stood as sentries in entryways of the palaces of Chan Chan. This vast adobe city, the remains of which can still be seen outside of the modern city of Trujillo, thrived between ca. 1000 and 1470 CE, when it fell to the invading Inca army. Chan Chan encompasses some 8 square miles (20 km2), and is dominated by ten royal compounds with high perimeter walls thought to be the palaces, administrative centers, and, ultimately, funerary structures of the Chimú kings. The compounds contained grand open courtyards, walk-in wells, and ample storage facilities. Sixteenth-century accounts of the looting of these palaces describe the immense quantities of gold and silver that were found within their walls. Perhaps because of their contents, but also likely for social and political reasons, security was clearly a concern at Chan Chan and access was highly restricted. The compounds had a single entrance, on the north perimeter wall, and progress through the palaces was impeded by a system of baffled entries, further controlling the flow of visitors. Wooden guardians such as the present example were surely part of a complex system designed to protect the exclusive and sacred spaces of the Chimú elite and to celebrate eternally the rituals held within them. Similar, usually smaller, wood sculptures were also part of free-standing processional tableaux and architectural models deposited in burials (see, for example, Jackson, 2004; Uceda, 1999, 2011), perhaps for related purposes.

*It is also possible, however, that the object the figure grasps represents a type of flute known as a quena. Matthew Helmer excavated two similar, but slightly smaller wood sculptures in a Chimú-Inca period burial at Samanco, in the Nepeña Valley (Helmer 2015:fig. 4.22). Helmer interprets the somewhat longer and thinner cylindrical objects on the Nepeña sculptures as flutes, and for good reason, as the tomb contained some 16 actual cane flutes. Given the shorter, wider proportions of the present example, however, and the taper of the top and bottom, the form more closely resembles the characteristic drinking vessels from Chornancap, a Lambayeque site (Wester La Torre, 2016:315, fig. 197), and a set of Chimú silver vessels reportedly from the Chicama Valley (including MMA 1978.412.181, .183, .185, .186).

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of Ancient American Art, 2018

References and Further Reading

Campana Delgado, Cristóbal. Chan Chan del Chimo. Lima: Editorial Orus, 2006.

Cummins, Thomas B.F. Toasts with the Inca; Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Helmer, Matthew. The Archaeology of an Ancient Seaside Town: Performance and Community at Samanco, Nepeña Valley, Peru (ca. 500-1 BC). Oxford: Archaeopress, 2015.

Jackson, Margaret. “The Chimú Sculptures of Huacas Tacaynamo and El Dragon, Moche Valley, Peru.” Latin American Antiquity vol. 15, No. 3 (2004), pp. 298-322.

Pillsbury, Joanne. “Imperial Radiance: Luxury Arts of the Incas and their Predecessors,” in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim Richter, pp. 33-43. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017.

“Reading Art without Writing: Interpreting Chimú Architectural Sculpture,” in Dialogues in Art History, from Mesopotamian to Modern: Readings for a New Century, Elizabeth Cropper, ed., pp. 72-89. Studies in the History of Art 74, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Symposium Papers LI. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, Distributed by Yale University Press, 2009.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017).

Pillsbury, Joanne, Patricia Sarro, James Doyle, and Juliet Wiersema. Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Ríos, Marcela, and Enrique Retamozo. 1982. Vasos ceremoniales de Chan Chan. Lima: ICPNA, 1982.

Uceda, Santiago. “Esculturas en miniatura y una maqueta en madera: El culto a los muertos y a los ancestros en la época Chimú,” Beiträge zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 19 (1999), pp. 259-311.

Uceda, Santiago. “Las maquetas Chimú de las Huacas de la Luna y sus contextos,” in Modelando el mundo: Imágenes de la arquitectura precolombina, ed. Cecilia Pardo, pp. 144-163. Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2011.

Wester La Torre, Carlos. Chornancap: Palacio de una gobernante y sacerdotisa de la cultura Lambayeque. Chiclayo: Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, 2016.

Artwork Details

- Title: Standing male figure

- Artist: Chimú artist(s)

- Date: 1300–1470 CE

- Geography: Peru, North Coast

- Culture: Chimú

- Medium: Wood

- Dimensions: H. 28 5/16 x W. 9 3/8 x D. 7 1/4 in. (71.9 x 23.8 x 18.4 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

- Object Number: 1979.206.774

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.