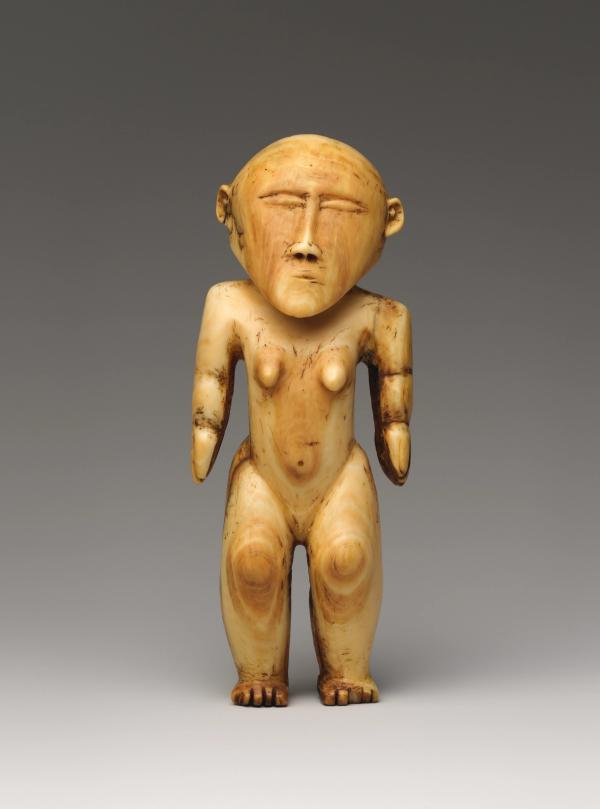

Female figure (’otua fefine)

This striking example was carved from the creamy core of the polished tooth of a sperm whale. The figure’s honey-colored patina was achieved by smoking the figure over smoldering sugary tubers from the ti plant (Cordyline fruticose) and then rubbing with oil. Not only did this accentuate the ivory’s natural grain (giving it a rich reddish color which was an important element of its aesthetic), the resulting shimmer of the surface conveyed something of the essence of divine, sacred light. The creator of this remarkable carving worked the material to spectacular effect, choosing to align the grain of the whale ivory at the center of the figure so that fine concentric circles emanate out from the figure’s knees and navel and embellish the lower part of her face. Carefully worked incisions create a series of raised ridges which delineate facial details including her eyebrows, a pair of closed eyes and neatly executed nose. The small, partially closed mouth adds to the overall impression of calm serenity and repose.

The figure is robust with a strong physique and rounded breasts, the triangular head prominent and well-defined with a strong chin that juts out dramatically over her neck and shoulders. Her strong arms and flattened palms frame her body, containing the forces of vital energy within her. The gently flexing stance is typical of the carving style of the Ha’apai Islands, at the center of the Tongan archipelago. The natural contour of the original whale tooth can be determined by the angle of the figure’s compact body as she tips gently to the left. A small whale ivory peg in the left hand arm is an original repair from several centuries ago. Wrapped in barkcloth (smeared with yellow turmeric or red ochre), the figures were secreted away with other sacred objects in specially constructed fiber god houses which acted as small shrines. When activated with ritual chants in ceremony, they served as dynamic channels – a vessel (or vaka) through which the spirits of the ancestral gods could pass. Many, like this one, have a suspension hole in the back of the head or neck, which would allow for a suspension cord of plaited coconut fiber so that they could be worn on ceremonial occasions by chiefly women as prestige ornaments, either as single pendants or as an element of a larger necklace.

Ivory figures were venerated as sacred objects in the Ha’apai Islands as well as in Fiji, where this example was collected in 1868. There are sixteen of these single whale ivory female figures extant in the world. Their stylistic features show strong affinities with wood figures from Ha’apai, but differ greatly from known examples of Fijian sculpture, indicating that they were almost certainly created in the Ha’apai group and subsequently traded to Fiji. Polynesian islanders did not hunt whales but waited for chance strandings on the reef where they would follow appropriate protocols before going out to harvest and distribute the individual ivories collected. Whale teeth continue to be highly valued and prestigious items today.

Maia Nuku, 2020 Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator for Oceanic Art

Published

Kjellgren, Eric. Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 287-9, no. 172. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007

Kjellgren, Eric. How to Read Oceanic Art, pp. 146-9, no. 35. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014

Nuku, Maia. ATEA: Nature and Divinity in Polynesia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Winter 2019, p. 12-3.

Exhibited

Newton, Douglas. The Nelson A. Rockefeller Collection: Masterpieces of Primitive Art. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978.

Further Reading

Niech, Roger. ‘Tongan figures: from goddesses to missionary trophies to masterpieces’, The Journal of the Polynesian Society Vol. 116, No. 2 (JUNE 2007), pp. 213-268

Artwork Details

- Title: Female figure (’otua fefine)

- Date: Early 19th century

- Geography: Tonga, Ha'apai Islands

- Culture: Ha'apai Islands

- Medium: Whale ivory

- Dimensions: H. 5 1/4 in. × W. 2 in. × D. 1 1/2 in. (13.3 × 5.1 × 3.8 cm)

- Classification: Bone/Ivory-Sculpture

- Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

- Object Number: 1979.206.1470

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1719. 'Otua fefine (deity figure), Ha'apai Islands artist

Visesio Siasau

KATERINA TEAIWA (NARRATOR): This whale ivory figure represents Hikule’o, the powerful Tongan goddess of creation and destruction.

VISESIO SIASAU: Hikule’o is a prominent god in qualities of life. Hikule’o on the form of the whale ivory is the catalyst of our knowledge of death, darkness, fertility, space, and divinity.

I am Visesio Siasau, creator.

KATERINA TEAIWA: Visesio Siasau is one of Tonga’s most prominent contemporary artists. He creates contemporary forms of Tongan deities in materials that include Perspex, glass, stone, bronze, and wood.

VISESIO SIASAU: I think if the ancestors were here in this time accessing all this material, they will be doing something that is way beyond my time.

In Tonga, we just experienced the biggest eruption of an underwater volcano, and the immensity of the blast, the vibration of the sound that touches our emotion, followed by a tsunami that natural event brought back the light of Hikule’o.

KATERINA TEAIWA: In Tongan cosmology, the relationships between people, the land, space, and time is known as vava. Vava space isn’t empty. Instead of separating things, it holds everything together.

VISESIO SIASAU: When we started to speak about Hikule’o, we are the Hikule’o. It wasn't like saying that: Here are our gods; we are the gods and goddesses. Because all these were done through the cosmic relationship of people.

KATERINA TEAIWA: This sculpture was expertly carved from the single tooth of a sperm whale. At the top, you can see the natural curvature of the tooth.

VISESIO SIASAU: Ivory is very significant to our culture.

KATERINA TEAIWA: But Tongans are not known to have hunted whales.

VISESIO SIASAU: When they come aground at a beach, then our ancestor took those teeth. That is the biggest animal that we have, in Tonga, as water is an extension of our land. That water doesn't belong to anyone; it belongs to all land. And connected every land and nation around the world. Allowing us, humanity, to survive. Letting us shift from one place to another, without a passport.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.