Female figurine

Not on view

This female figurine resembles other Inca metal figurines, often associated with the ritual performance of capac hucha, in terms of its appearance and design. Made of hammered sheet, of the approximate composition of 52% silver and 44% gold, by XRF, the figurine shows a woman standing with arms and hands close to the chest. Her hair is pulled back, extending to the lower back, into two tresses that have been tied at this end. Capac hucha has been defined in varied ways by 16th century Spanish chroniclers (Cieza de León 1959, 190-193; Diez de Betanzos 1996, 46, 132), but they note that it typically involves offerings in Cusco or in provincial regions made in honor of the Sun or in reverence of the Sapa Inca, the paramount Inca ruler. In some cases, it may involve gathering children from provinces, bringing them to Cusco, and then sending them to distant locations along with a range of other objects, including metal figurines, to be sacrificed and buried (see Diez de Betanzos 1996, 132). As with other instances of capac hucha assemblages that have been identified archaeologically (Gibaja et al. 2014; King 2016; Onuki and Rosas 2000), this figurine likely would have been dressed, wrapped in textiles fastened with pins (tupus) when it was deposited and accompanied by Inca ceramic and/or wooden vessels as well as other figurines made of metal or Spondylus spp. and the remains of the children sacrificed. However, Inca figurines have been deposited in contexts from which human remains have not been recovered, in a form of ritual practice separate from capac hucha (cf. Farrington and Raffino 1996, 73 on figurines from the main plaza or Haukaypata at Cusco, and Rojas et al. 2012 on a figurine from an Inca offering at the Moche site of Huaca de la Luna).

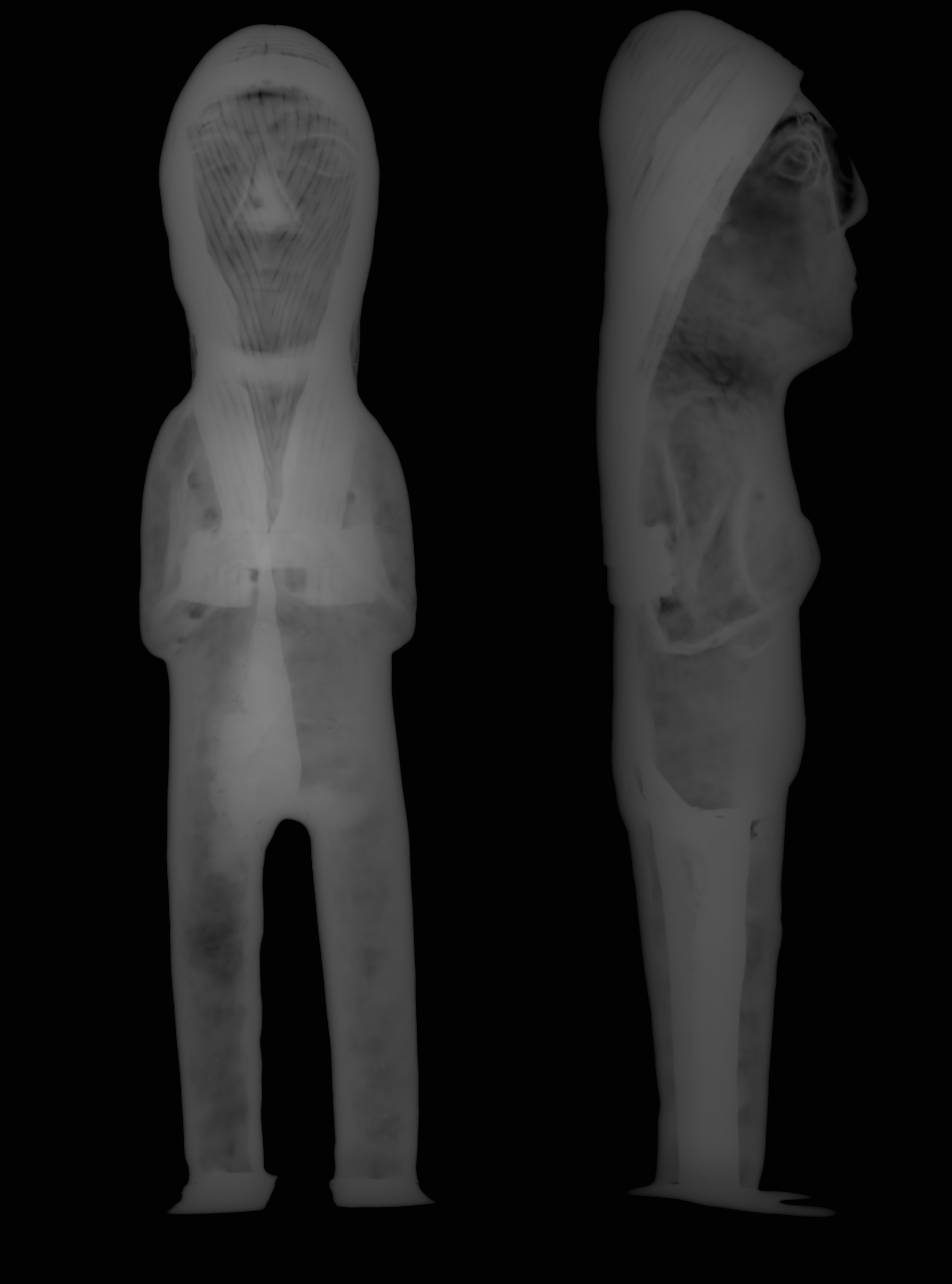

The figurine is comprised of at least five sheet components that have been joined together to form a hollow figure (see image 4): the hair; the head and body; a gusset in the genital region (see image 5); and two separate feet. Several features of the face and body were added before the head-body sheet was formed into a hollow cylinder to be joined to the other components. The arms, hands, two breasts, and groin area were shaped from the reverse side of the sheet followed by chasing from the front. The hands were shaped by fine hammering from the reverse side of the sheet, now hidden from view, and the vagina and individual fingers were distinguished by engraving or tracing (see image 6). Unlike other figurines (e.g., 1979.206.1058 ), the toes on the present figurine have not been indicated.

The joins of the different sheet components were achieved through soldering and welding (involving pressure and/or heating [cf. Lechtman 1996]). Further joins were made in the torso and the legs. On the torso’s reverse, the proper left end of the sheet overlaps the proper right end. There is a region of porosity that extends to the top of the proper right leg, visible macroscopically and by x-ray, that indicates the use of soldering to achieve the join in this area. Seams are visible on the inside-facing areas of each leg (see image 7).

The texture of the hair was achieved through engraving (see image 8). There is variation in the engraving between long continuous lines and series of distinct segments. There is a central line dividing the hair in half that also has been engraved, and this line terminates at the top of the head while in other cases (e.g., 1979.206.336 ), the central line extends farther down the back. The profile x-ray shows that the dome-shaped hair piece slightly overlaps the edges of the head, which is open at the back, but hidden to the viewer. Unlike other figurines (e.g., Field Museum 4450 from Isla de la Plata) (Cockrell et al. n.d.), the legs have been secured to the feet by flat flanges extending from the bottom edges onto the top of the feet and then soldered in place. Due to the large amounts of silver in the metal, the face and body show a combination of red and black silver-gold sulfide corrosion layers.

There tend to be three height groups (5-7 cm, 13-15 cm, 22-24 cm) among this corpus of Inca anthropomorphic figurines in metal (see McEwan 2015, 282, n. 15), and this figurine is in the middle height group. While the corpus of Inca figurines in metal—of humans and camelids—shows a range of internal similarities in shape and design, there are nuances to each, such as the joining of the legs to the feet, which suggest the work of different metallurgists. Inca leaders drew on metallurgists from Chan Chan, Pachacamac, and other locations to produce work. The Inca artists built on a Central Andean tradition centered on shaping metal as a solid, that is, by hammering, and using copper, silver, and gold, and alloys of these three metals, to make objects (Lechtman 2007, 320-1).

Technical notes: Optical microscopy, X-radiography, and XRF conducted in 2017.

Bryan Cockrell, Curatorial Fellow, AAO

Beth Edelstein, Associate Conservator, OCD

Ellen Howe, Conservator Emerita, OCD

Caitlin Mahony, Associate Conservator, OCD

2017

Published References

Burger, Richard L., and Lucy C. Salazar. Machu Picchu: unveiling the mystery of the Incas. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004, cat. no. 168.

Pimentel, Victor, ed. Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and the Moon. Milan: Five Continents Editions, 2013, cat. no. 125.

Further Reading

Cieza de León, Pedro de. The Incas. Edited by Victor Wolfgang von Hagen. Translated by Harriet de Onis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, [1553] 1959.

Cockrell, Bryan, McEwan, Colin, Williams, Patrick Ryan, and Laure Dussubieux. “The Ritualized Production of an Inca Assemblage from Isla de la Plata, Ecuador”. Unpublished manuscript.

Diez de Betanzos, Juan. Narrative of the Incas. Translated and edited by Roland Hamilton and Dana Buchanan. Austin: University of Texas Press, [1551-57] 1996.

Farrington, Ian, and Rodolfo Raffino. “Mosoq suyukunapa tariqnin: Nuevos hallazgos en el Tawantinsuyu.” Tawantinsuyu 2 (1996): 73-77.

Gibaja Oviedo, Arminda M., Gordon F. McEwan, Melissa Chatfield, and Valerie Andrushko. “Informe de las posibles capacochas del asentamiento arqueológico de Choquepujio, Cusco, Perú.” Ñawpa Pacha 34, no. 2 (2014): 147-175.

King, Heidi. “Further Notes on Corral Redondo, Churunga Valley.” Nawpa Pacha 36, no. 2 (2016): 95-109.

Lechtman, Heather. “Technical Descriptions.” In Andean Art at Dumbarton Oaks, edited by Elizabeth Hill Boone. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996.

———. “The Inka, and Andean Metallurgical Tradition.” In Variations in the Expression of Inka Power, edited by Richard L. Burger, Craig Morris, and Ramiro Matos Mendieta, 313- 355. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2007.

McEwan, Colin. "Ordering the Sacred and Recreating Cuzco," in The Archaeology of Wak'as: Explorations of the Sacred in the Pre-Columbian Andes, edited by Tamara L. Bray, 265-291. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Onuki, Yoshio, and Fernando Rosas Moscoso. Exposición del gran Inca eterno: La tristeza de la niña "Juanita". Lima: Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú and Museo Santuarios Andinos, 2000.

Rojas, Carol, Moisés Tufinio, Ronny Vega, and Mirtha Rivera. “Unidad 16 - Plataforma I de Huaca de la Luna.” In Proyecto Arqueológico Huaca de la Luna: Informe técnico 2011, edited by Santiago Uceda and Ricardo Morales, 75-127, Trujillo: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Trujillo, 2012.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.