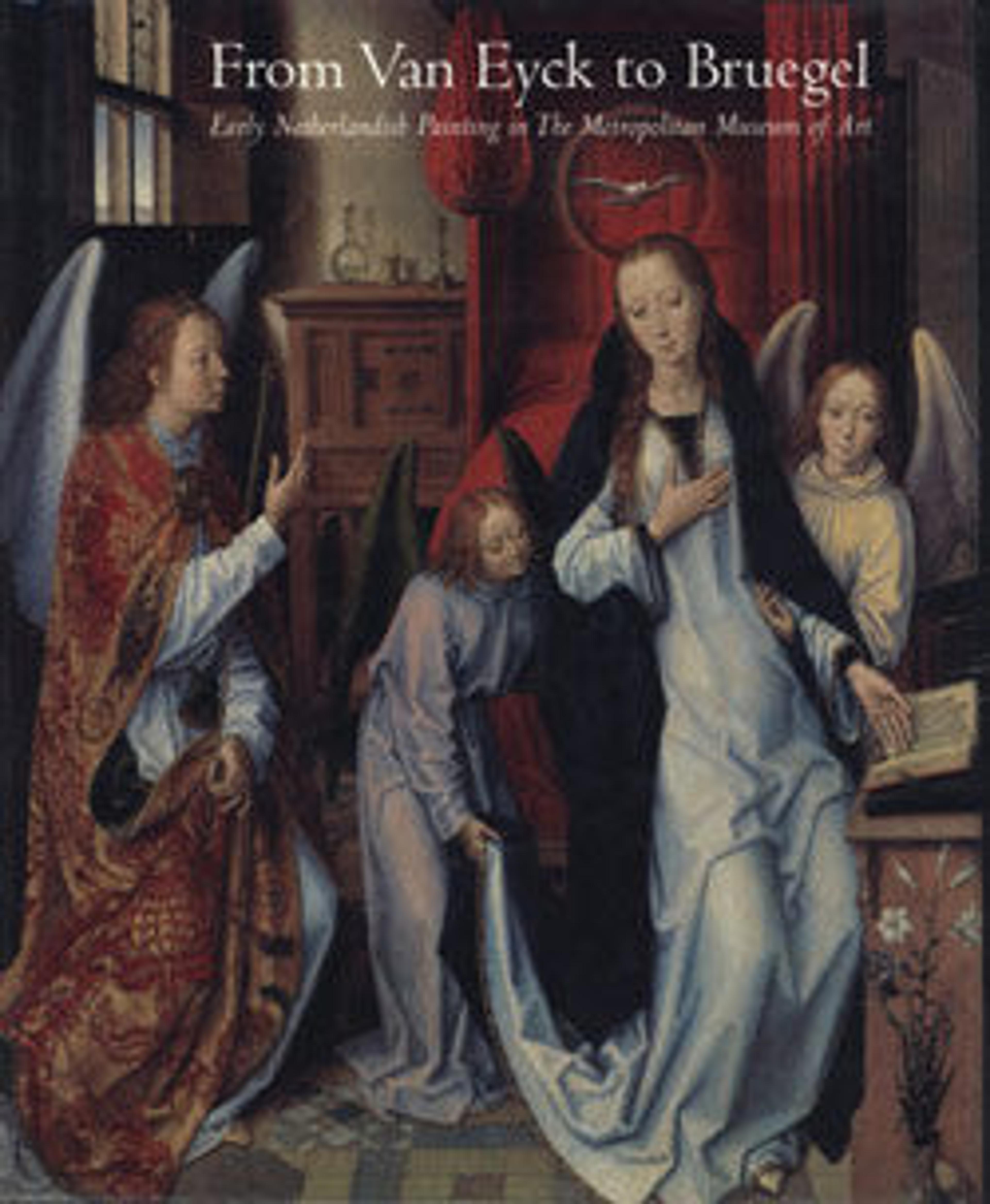

Virgin and Child

The half-length breastfeeding Virgin, or the Maria lactans, was one of the most popular themes for paintings of the Burgundian Netherlands. The composition of the painting derives partly from Dieric Bouts’s Virgin and Child in the National Gallery, London, combined with features originating in Rogier van der Weyden’s paintings. Technical studies suggest that this painting was made by an assistant in the Bouts workshop, thereby attesting to the enterprise of a thriving studio responding to the popular demand for this type of devotional image.

Artwork Details

- Title: Virgin and Child

- Artist: Workshop of Dieric Bouts (Netherlandish, Haarlem, active by 1457–died 1475)

- Date: 1475–99

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 11 1/2 x 8 1/4 in. (29.2 x 21 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

- Object Number: 49.7.18

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.