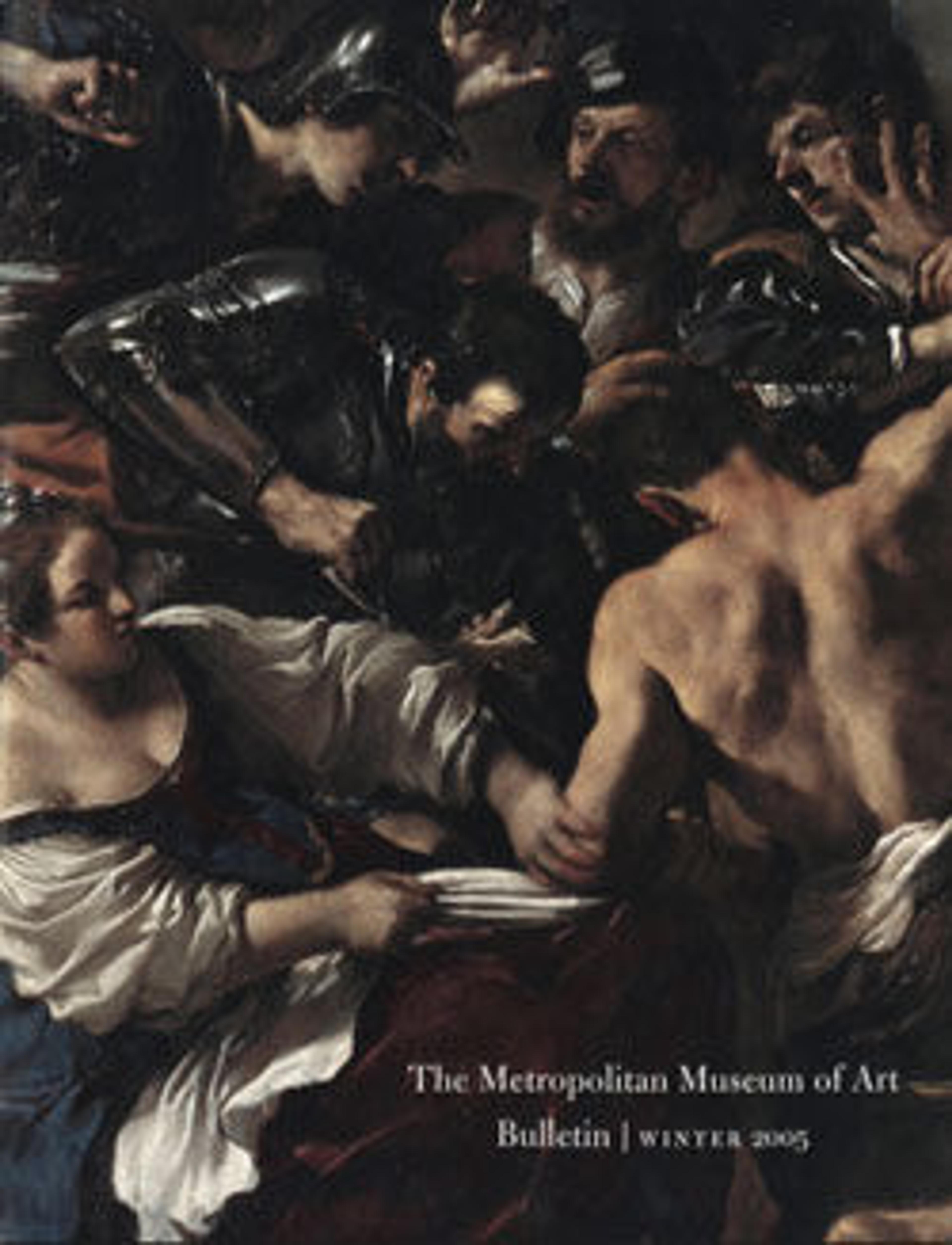

The Parable of the Mote and the Beam

Trained in Rome, Fetti evolved a style of animated, feathery brushstrokes that allows the eye to penetrate layers of the paint surface. In 1614 Fetti moved to Mantua, where he worked for Ferdinando Gonzaga alongside his sister and pupil, Lucrina Fetti. This painting is one of thirteen illustrations of Gospel parables painted in about 1619 for Gonzaga’s studiolo (a small private study, often filled with books and art). It represents an admonition by Jesus: “And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?”

Artwork Details

- Title: The Parable of the Mote and the Beam

- Artist: Domenico Fetti (Italian, Rome (?) 1591/92–1623 Venice)

- Date: ca. 1619

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 24 1/8 x 17 3/8 in. (61.3 x 44.1 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1991

- Object Number: 1991.153

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.