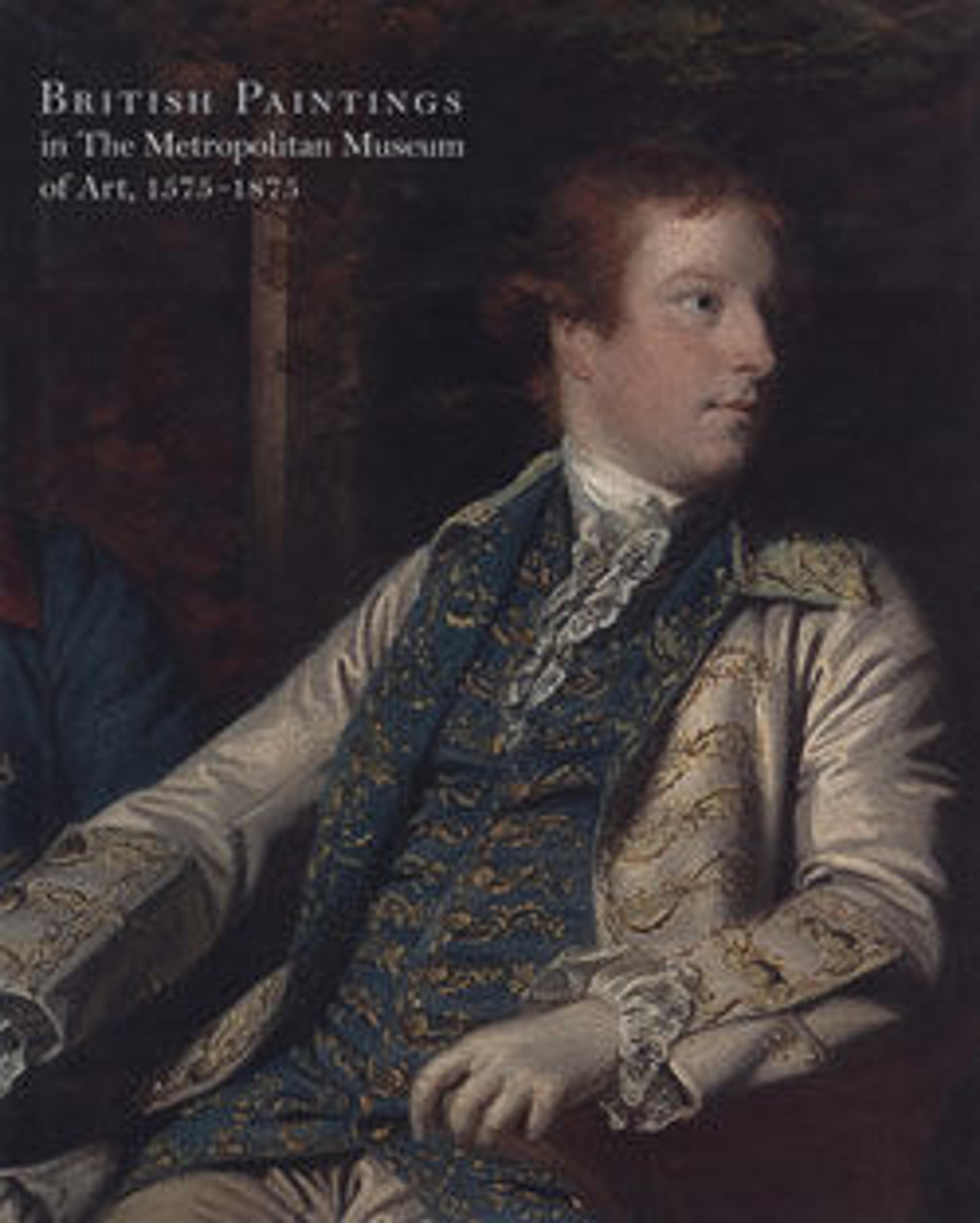

A Boy with a Cat—Morning

Well-to-do art collectors of the eighteenth century enjoyed "fancy pictures" such as this, which provided an idealized and sentimental image of poor children. The model for this particular work, Jack Hill, was a local boy whom Gainsborough’s daughter considered adopting. Although the child’s vulnerable situation may prompt an emotional response, Gainsborough’s interest in this material appears to have been largely aesthetic. Sir Joshua Reynolds praised Gainsborough after his death for the "interesting simplicity and elegance of his little ordinary beggar-children."

Artwork Details

- Title:A Boy with a Cat—Morning

- Artist:Thomas Gainsborough (British, Sudbury 1727–1788 London)

- Date:1787

- Medium:Oil on canvas

- Dimensions:59 1/4 x 47 1/2 in. (150.5 x 120.7 cm)

- Classification:Paintings

- Credit Line:Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889

- Object Number:89.15.8

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.