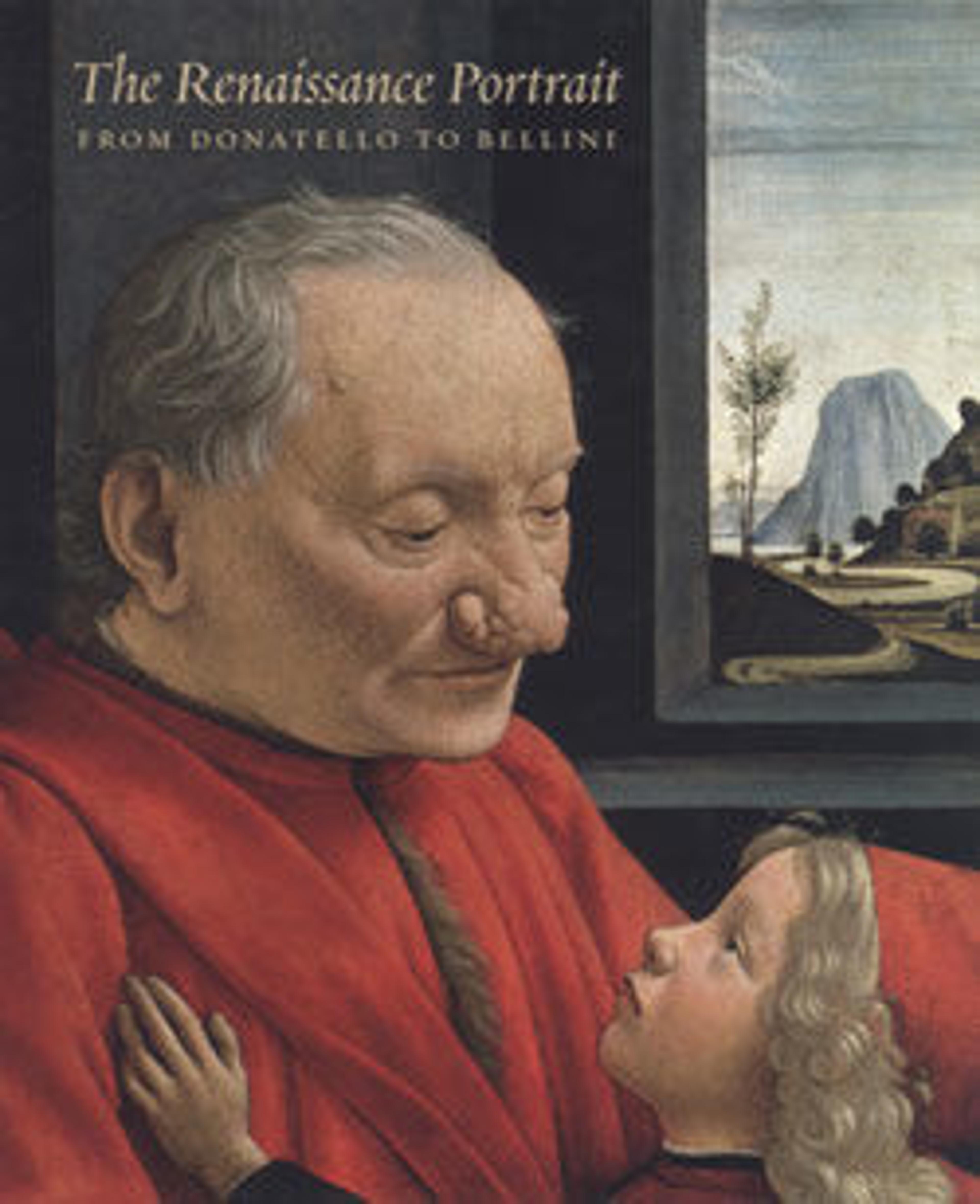

Francesco Sassetti (1421–1490) and His Son Teodoro

This dynastic portrait shows the Florentine banker Francesco Sassetti and his young son Teodoro, born in 1479. Teodoro was named after his elder brother, who died that same year. The boy’s pose reflects the preference for presenting women and children in profile to accentuate their holiness and purity, while the frontal, contemplative gaze of his father emphasizes the wisdom (and worries) of age. Sassetti managed the Medici banks in Avignon, Geneva, and Lyons, and was an advisor to Piero de’ Medici and Lorenzo the Magnificent. The background shows an oratory built by Sassetti in Geneva.

Artwork Details

- Title: Francesco Sassetti (1421–1490) and His Son Teodoro

- Artist: Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico Bigordi) (Italian, Florence 1448/49–1494 Florence)

- Date: ca. 1488

- Medium: Tempera on wood

- Dimensions: Overall 33 1/4 x 25 1/8 in. (84.5 x 63.8 cm); painted surface 29 7/8 x 20 7/8 in. (75.9 x 53 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

- Object Number: 49.7.7

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.