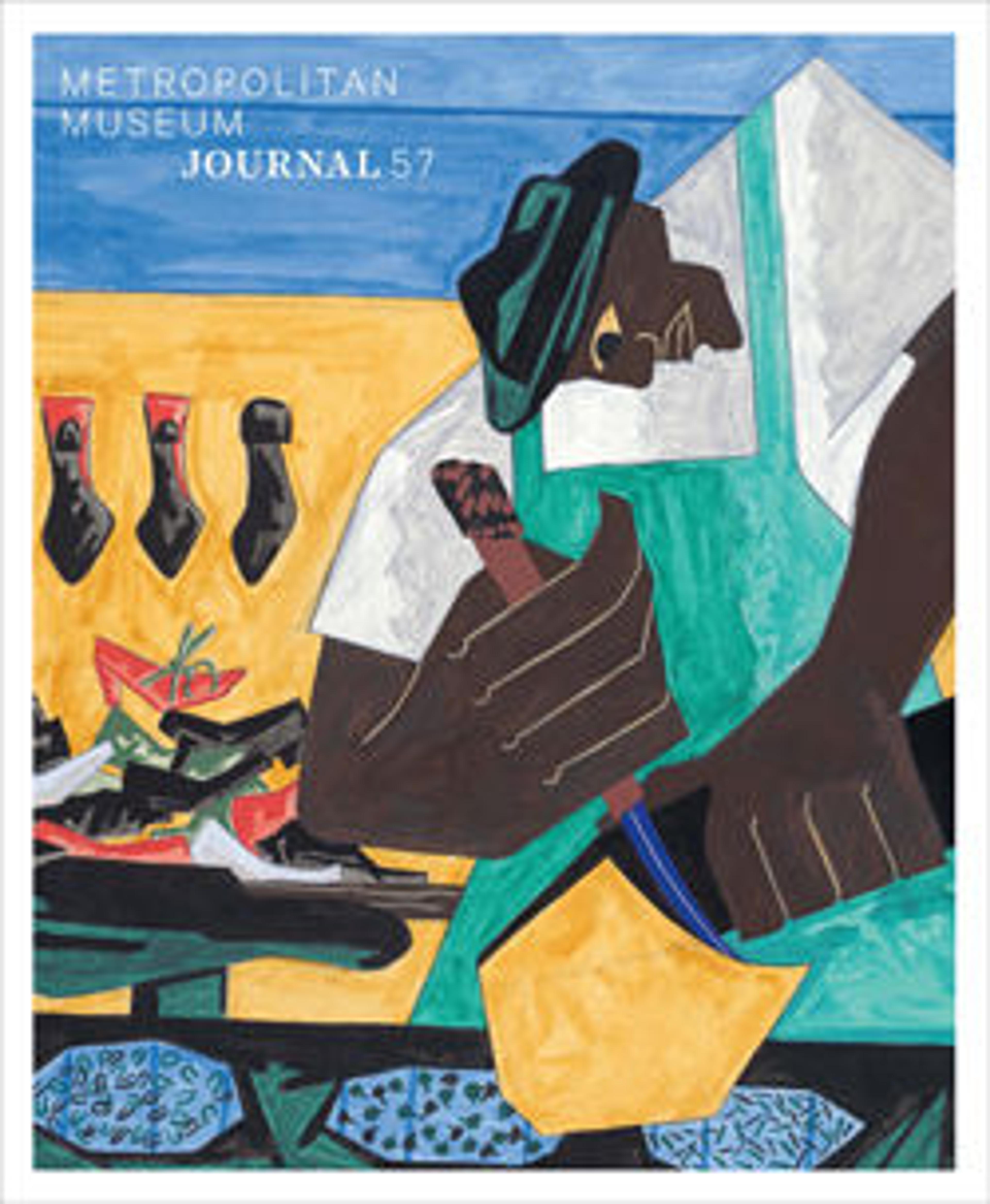

Saint Peter and Simon Magus

These four panels were commissioned in the 1460s by the Alessandri family in Florence in order to update a Gothic-style altarpiece painted 150 years earlier in the church of San Pier Maggiore. In them, the fifth-century bishop of Florence resuscitates a dead child on the square in front of San Pier Maggiore; the magician Simon Magus crashes to the ground at the feet of Emperor Nero when Saint Peter commands the demons who suspended him in midair to let him go; Saint Paul falls from his horse at the apparition of Christ; and Totila, king of the Goths, asks the blessing of Saint Benedict. From his work with Fra Angelico and the sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, Gozzoli evolved a style of great charm and narrative engagement.

Artwork Details

- Title: Saint Peter and Simon Magus

- Artist: Benozzo Gozzoli (Benozzo di Lese di Sandro) (Italian, Florence ca. 1420–1497 Pistoia)

- Medium: Tempera on wood

- Dimensions: 15 3/4 x 18 in. (40 x 45.7 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1915

- Object Number: 15.106.1

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.