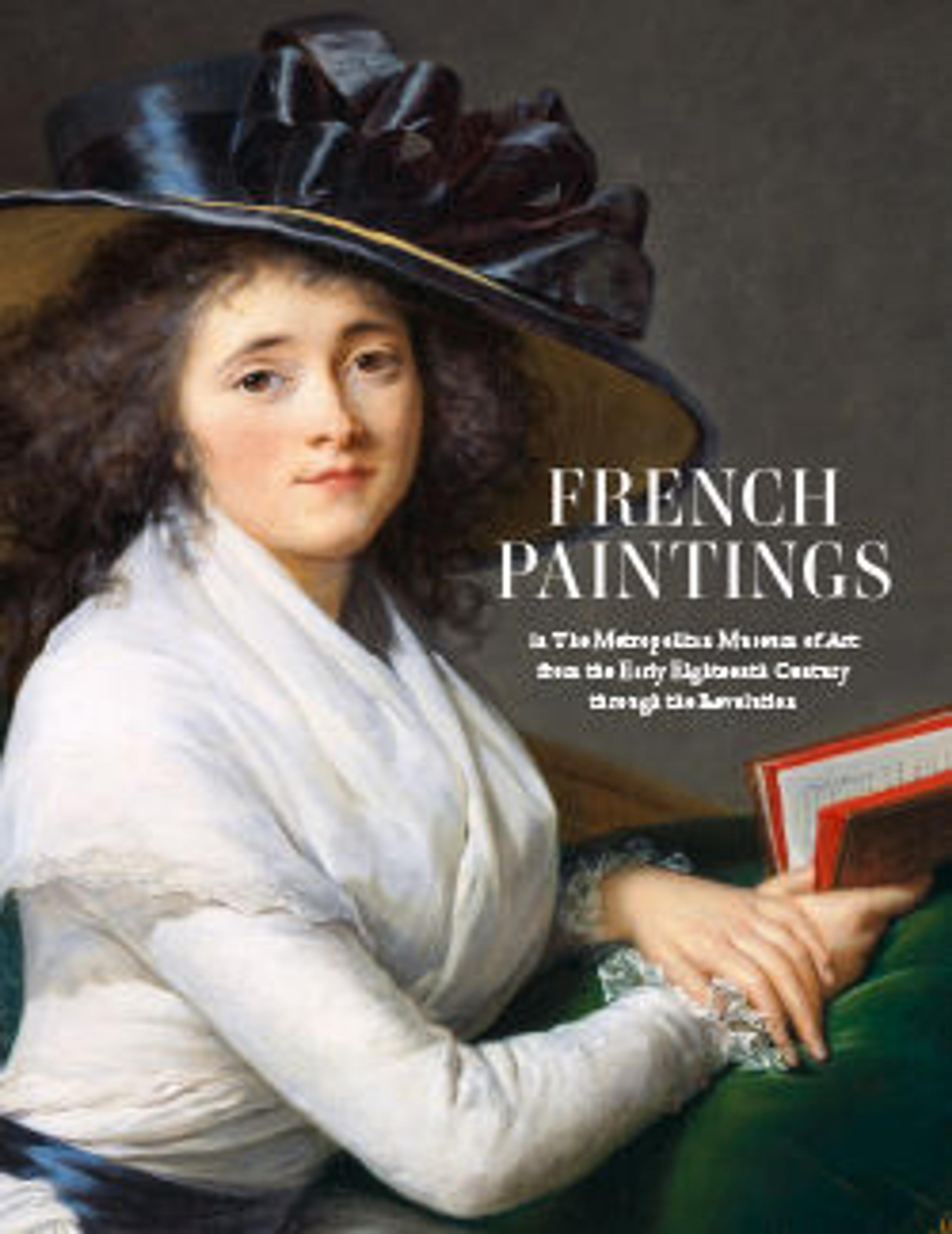

Charles Claude de Flahaut (1730–1809), Comte d'Angiviller

Greuze’s intelligence as a portraitist and colorist lends intimacy and liveliness to a formidable figure in the French artistic establishment, the comte d’Angiviller. In 1763, the year Greuze executed this painting and showed it at the Salon, Angiviller was in charge of the household of the eldest son of Louis XV, but he went on to become general director of the Batîments du Roi, roughly equivalent to a minister of culture who determined artistic careers. Greuze’s image makes a bravura performance of depicting the textures of formal winter dress, from the fur-lined silk coat with its elaborate frogged buttons to the vest embroidered with metallic thread.

Artwork Details

- Title: Charles Claude de Flahaut (1730–1809), Comte d'Angiviller

- Artist: Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French, Tournus 1725–1805 Paris)

- Date: 1763

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 25 1/4 x 21 1/4 in. (64.1 x 54 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Gift of Edith C. Blum (et al.) Executors, in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Blum, 1966

- Object Number: 66.28.1

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.