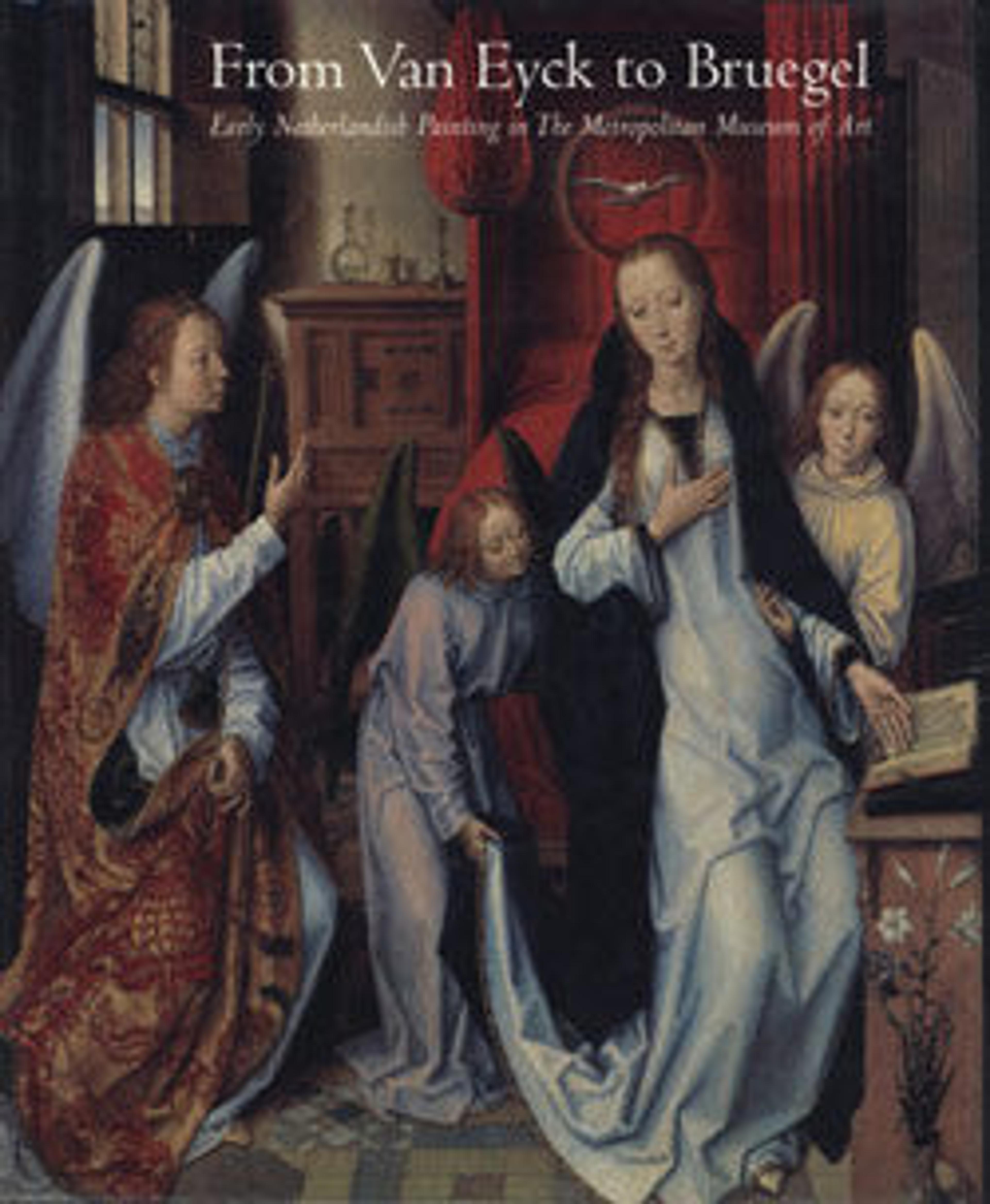

Saints Michael and Francis

This panel was originally part of a large Spanish altarpiece. The artist placed both figures in niches, but in contrast to the frontal, ascetic image of Saint Francis, who is neatly contained within the shallow space, Saint Michael extends beyond his niche. Stabbing the dragon at his feet, the archangel gazes earthward at the apocalyptic vision—a walled, smoking city—that is reflected in his decorative shield. This latter detail hints at Juan de Flandes’s Netherlandish origin. The introduction of a gold background and the broad painting technique, however, reveal his efforts to adapt his style to Spanish taste.

Artwork Details

- Title: Saints Michael and Francis

- Artist: Juan de Flandes (Netherlandish, active by 1496–died 1519 Palencia)

- Date: ca. 1505–9

- Medium: Oil on wood, gold ground

- Dimensions: Overall, with added strips at right and bottom, 36 7/8 x 34 1/4 in. (93.7 x 87 cm); painted surface 35 3/8 x 32 3/4 in. (89.9 x 83.2 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Mary Wetmore Shively Bequest, in memory of her husband, Henry L. Shively, M.D., 1958

- Object Number: 58.132

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.