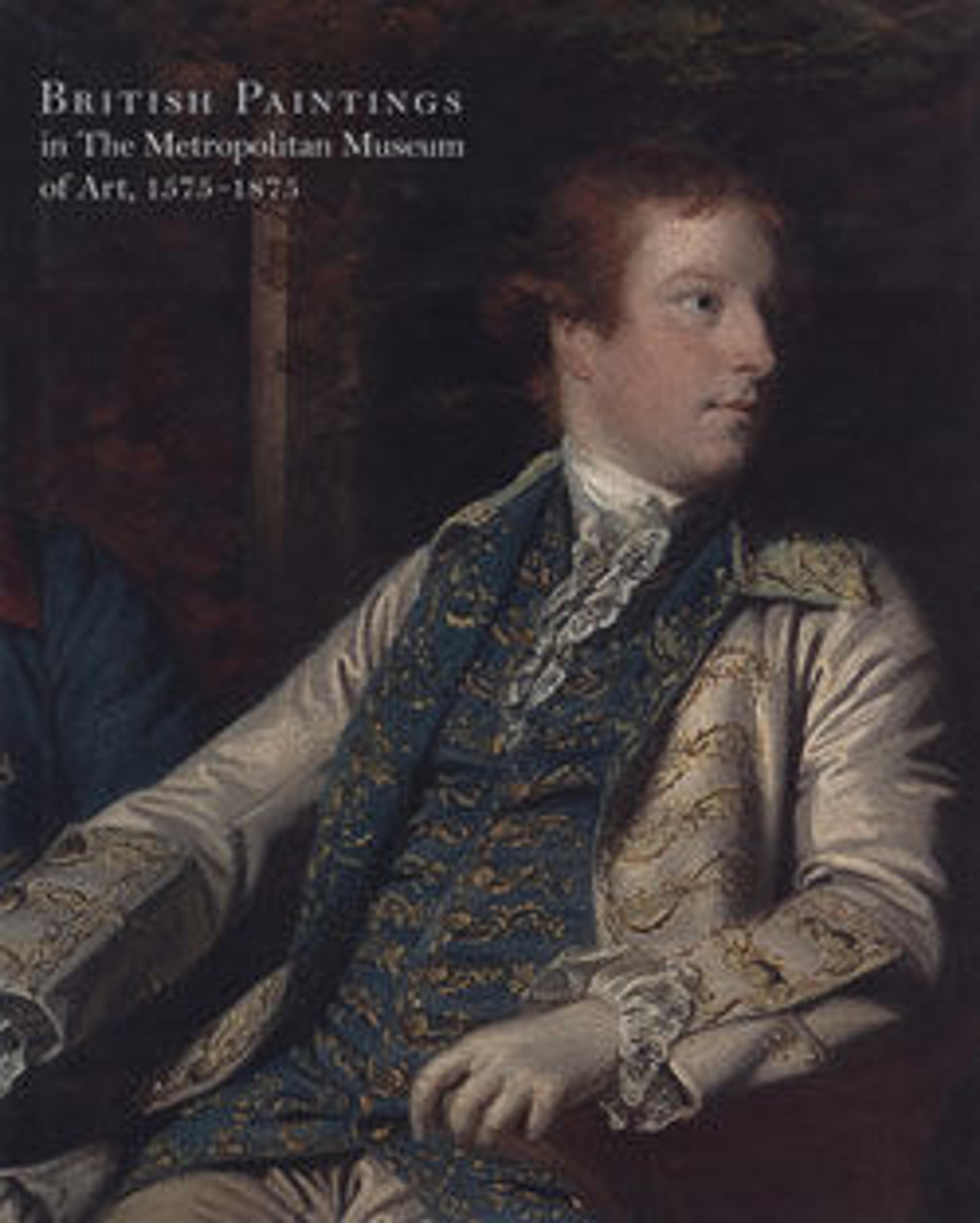

Copy after Rubens's "Wolf and Fox Hunt"

In or about 1825, while preparing to undertake his first major oil, The Hunting of Chevy Chase (City Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham, England), the young Landseer made a pilgrimage to the country home of Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton, to sketch the monumental seventeenth-century Flemish painting Wolf and Fox Hunt, by Peter Paul Rubens (now in The Met’s collection). Landseer found inspiration in the picture’s subject, bravura brushwork, and sparkling light effects. Hunting scenes never went out of fashion in the country houses of Britain, and Landseer quickly became the acknowledged modern master of the genre.

Artwork Details

- Title: Copy after Rubens's "Wolf and Fox Hunt"

- Artist: Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (British, London 1802–1873 London)

- Date: ca. 1824–26

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: 16 x 23 7/8 in. (40.6 x 60.6 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1990

- Object Number: 1990.75

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.