The Artist: For a biography of Quinten Massys, see the Catalogue Entry for the

Adoration of the Magi (

11.143)

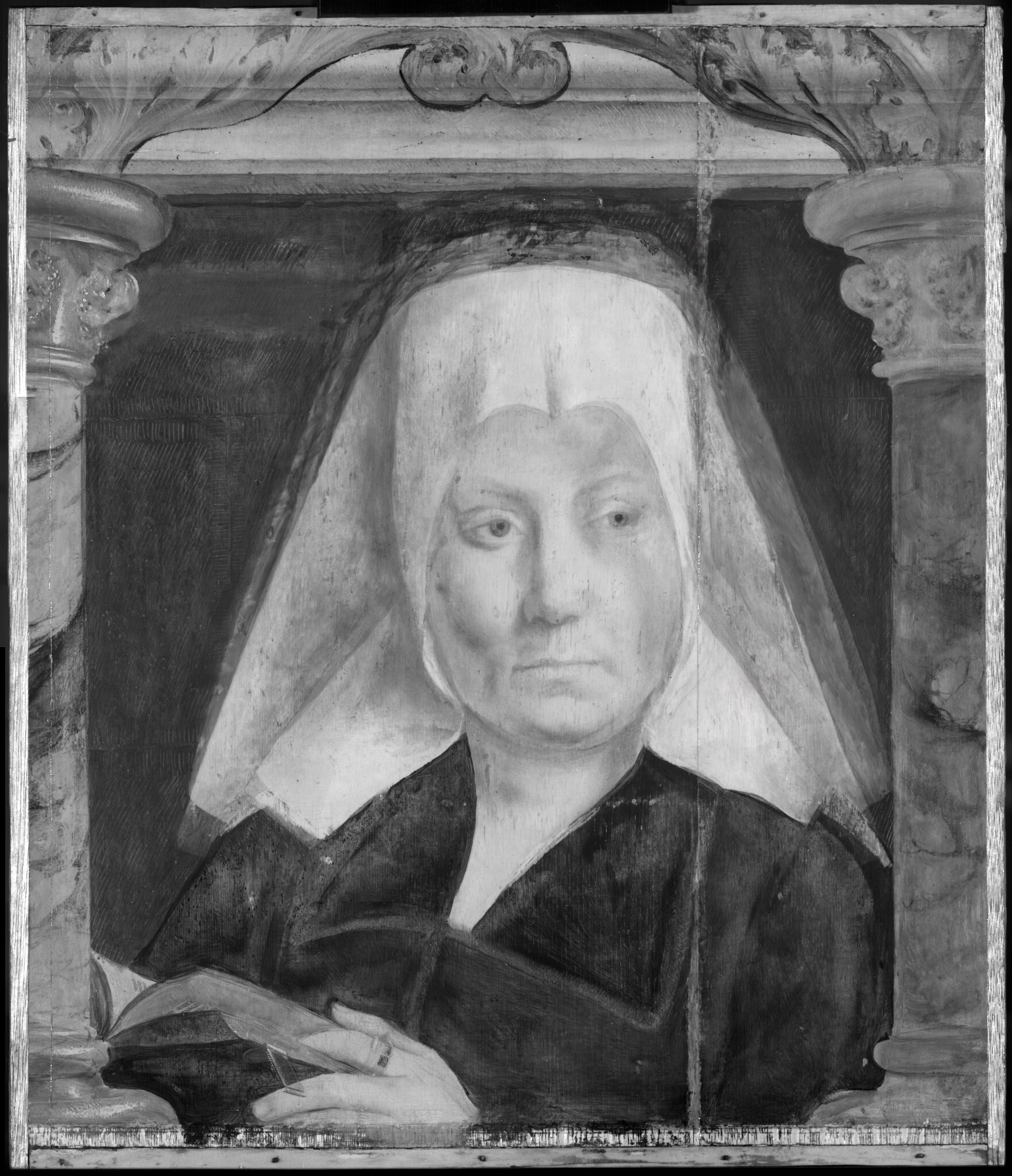

The Subject and its Context: In a startling departure from conventional devotional portraits, and with a dour expression, the middle-aged female sitter looks to her left, distracted from reading her book of hours. This sense of interruption is enhanced by the position of her fingers, one of which is inserted between the pages of her book, as if to hold her place. She is dressed well but conservatively, and wears three gold rings, one set with two precious stones. Her devotional book, with its strewn flowers on gold borders, gilt-gauffered edges, and gilt clasp is an object of luxury. The book at once conveys the subject’s piety, literacy, and wealth. It is very similar to those made in the early-sixteenth-century workshops of Simon Bening (Silver 1964, p. 164) and the Master of James IV of Scotland.[1] Thus, although presented as a pious woman, seemingly occupied by her daily devotions, her dress, comportment, and surroundings also portray her elevated social status. Such conflated representational aims of the sitter—piety and wealth—were already well established earlier in portraiture. See, for example, Hans Memling’s

Tommaso di Folco Portinari and Maria Portinari (Maria Maddalena Baroncelli) in The Met’s collection (

14.40.626–27).

The lavish architectural setting of the painting includes two multicolored marble columns with golden capitals and bases, a stone lintel, and a superimposed arch with an acanthus leaf design. The latter is an Italianate motif, which in the early sixteenth century was becoming increasingly popular in Netherlandish art.[2] The convention of framing sitters with architectural motifs in this portrait and its pendant,

Portrait of a Man (private collection, Belgium; see fig. 1), shows the influence of Hans Memling’s portraiture mode of a generation earlier. Memling’s

Portrait of a Young Man at Prayer of about 1480 or later (National Gallery, London; fig. 2) similarly presents an extravagantly dressed sitter, before a dark background, and between multicolored marble columns with golden crocket capitals and bases.

How might these two pendant portraits have functioned or originally been installed? Ordinarily, both figures of devotional portraits gaze toward a holy image placed between them, as in The Met’s Portinari portraits mentioned above. Here, however, they look off to their left, beyond their confined spaces, as if momentarily distracted by something or someone not visible to the viewer. Perhaps this man and woman were meant to be displayed in an ecclesiastical setting, such as a family chapel within a church, where their portraits served a memorial function. If they were placed on a side wall, then the painter may have ingeniously planned the compositions to emphasize the allure of the devotional image of consequence at the chapel’s focus and its power to perpetually engage the couple in real time. Such an artistic invention enhances the notion of the perceived actual presence of the holy figure(s) in a painting or sculpture within the chapel as a result of the devotional practice of the couple.

The Attribution and Date: Max J. Friedländer (1928) first attributed the

Portrait of a Woman to Quinten Massys, and subsequently (1937) identified a pendant, a

Portrait of a Man, then in the Bodmer Collection in Zurich, later in the Collection of Mrs. H. von Schulthess-Bodmer, Schloss Au, Switzerland, and now in a private collection in Belgium (fig. 1). As Friedländer (1971, p. 34) so aptly put it, concerning Massys’s portraits: "Quentin [Massys] developed no system of portraiture to which he clung, but rather treated each case on its own merits, according to the type of sitter who posed for him. His portraits are all different—in posture, composition, background and “props.” They may be square-topped or arched above, bust-length, with or without hands, or half-length. The background may be neutral or consist of a landscape, an interior, an architectural framework. The attitude may be tranquil or agitated. Every possibility is explored and nothing is ever repeated."

Indeed, the two portraits are just as distinctive in their own way as are others in Massys’s oeuvre. They hung together (the private collection picture on loan) from 2008–12 in The Met’s galleries, allowing for the technical examination of their evolving design (see Technical Notes). They usually are believed to portray a husband and wife, given the coordination of their settings, general demeanor, and the fact that they both are interrupted from their devotions—she from her book of hours and he from saying his rosary. Contemporary Netherlandish paintings of married couples are usually made on separate but matching panels, with the man on the left and the woman on the right. Lorne Campbell (1990, p. 34) suggested that the two originally may have formed one picture on the same panel before being separated.[3] However, as the technical investigation shows, both were made of three vertical planks and there is no evidence that they ever were joined by dowels. Furthermore, when the two are placed side-by-side, the column details do not precisely match up (fig. 1), leading to the conclusion that they were not originally painted as contiguous, but framed separately.

The possible circumstances discussed above of the installation of these portraits in a chapel setting likely accounts for their evolving painting process, as is clear from their examination with infrared reflectography (see Technical Notes and figs. 7–8). Originally, the woman appeared before a tooled masonry background, which matched the one still evident in the

Portrait of a Man. The masonry may have been overpainted later with a dark monochrome background, or Massys may have added a translucent green glaze, intended to modify the brick background, which now has darkened and been heavily restored. Furthermore, the peak of the woman’s headdress was lowered in two separate stages to reach a final form beneath the lintel. Infrared reflectography also revealed that the acanthus leaf decoration was painted on top of the lintel in both portraits not long after the paintings initially were completed. This decorative effect may have been added to update more conservative paintings to the Italianate mode in vogue at the time or to be coordinated with architectural decoration in their destined location. Unfortunately, no other clues in either painting provide a definitive answer to this question.

The portrait pair have been dated as early as 1509–15 by Baldass (1933), Richardson (1941), Cutler (1968), and Campbell (1990). However, I believe that there are clues to a later date of the portraits found in Massys’s developing sense of informality and what Friedländer (1971, p. 35) so aptly described thus: “…Quentin’s growing insight into the human mind. More and more, he encompassed the essence of the individual, in terms of stature, attitude, expression, and gesture.” The Winterthur

Portrait of a Man of 1509 (fig. 3) shows Massys’s early interest in the psychological engagement of the sitter with the viewer, and the use of emphatic hand gestures to convey a sense of the figure’s personality. The 1517 Karlsruhe

Portrait of a Man (fig. 4) in pose and general demeanor is very similar to the Belgian private collection

Portrait of a Man, their hand gestures each in arrested motion. Finally, the

Portrait of a Scholar (Städel Museum, Frankfurt; fig. 5) of about 1525–30 develops these trends to their fullest. Here, the man’s articulated, expansive hand gesture and his unequivocal interaction with someone or something beyond the picture plane advances that same sense of communication initiated by Massys in The Met’s

Portrait of a Woman. Given these comparisons, it appears most likely that the portrait pair under discussion dates around 1520, that is, at the mid-point of Massys’s development of the humanist portrait.[4] In their somewhat uneasy relationship to each other, both physically near but psychologically and emotionally distant, the man and woman call to mind Jan Gossart’s equally unsettlingly candid double portrait in the National Gallery, London, of around 1525–30 (fig. 6).[5]

Maryan W. Ainsworth 2020

[1] My thanks to Thomas Kren for his opinion about the decoration of the Book of Hours (email of August 7, 2020 to the author).

[2] Concerning the popularity and adoption of vegetal forms in architecture as a humanist tendency especially in Germany at the turn of the sixteenth century, see Ethan Matt Kavaler,

Renaissance Gothic, New Haven and London, 2012, pp. 199–229, esp. pp. 223–29.

[3] As Lorne Campbell showed (“A Double Portrait by Memling,”

Connoisseur 194 (1977) no. 781, pp. 186–89), an example of such portraits being joined together by dowels on the same panel is Hans Memling’s

Portrait of an Elderly Couple of about 1470–75 (long ago separated and since in the Gemäldegalerie, SMPK, Berlin, and Musée du Louvre, Paris). Furthermore, in the

Counts and Countesses of Flanders series of 1480 (Groot Seminarie, Bruges) and Justus of Ghent’s series of

Famous Men of the mid-1470s (mostly Musée du Louvre, Paris), several figures appear together on each panel within simple architectural framing structures (Campbell 1990, p. 109).

[4] Dendrochronology was not possible because the panel was thinned, trimmed, and cradled, and there are wood strips added to all of the edges.

[5]

Man, Myth, and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart’s Renaissance, The Complete Works, Maryan W. Ainsworth, ed., exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010, no. 53, pp. 276–79.