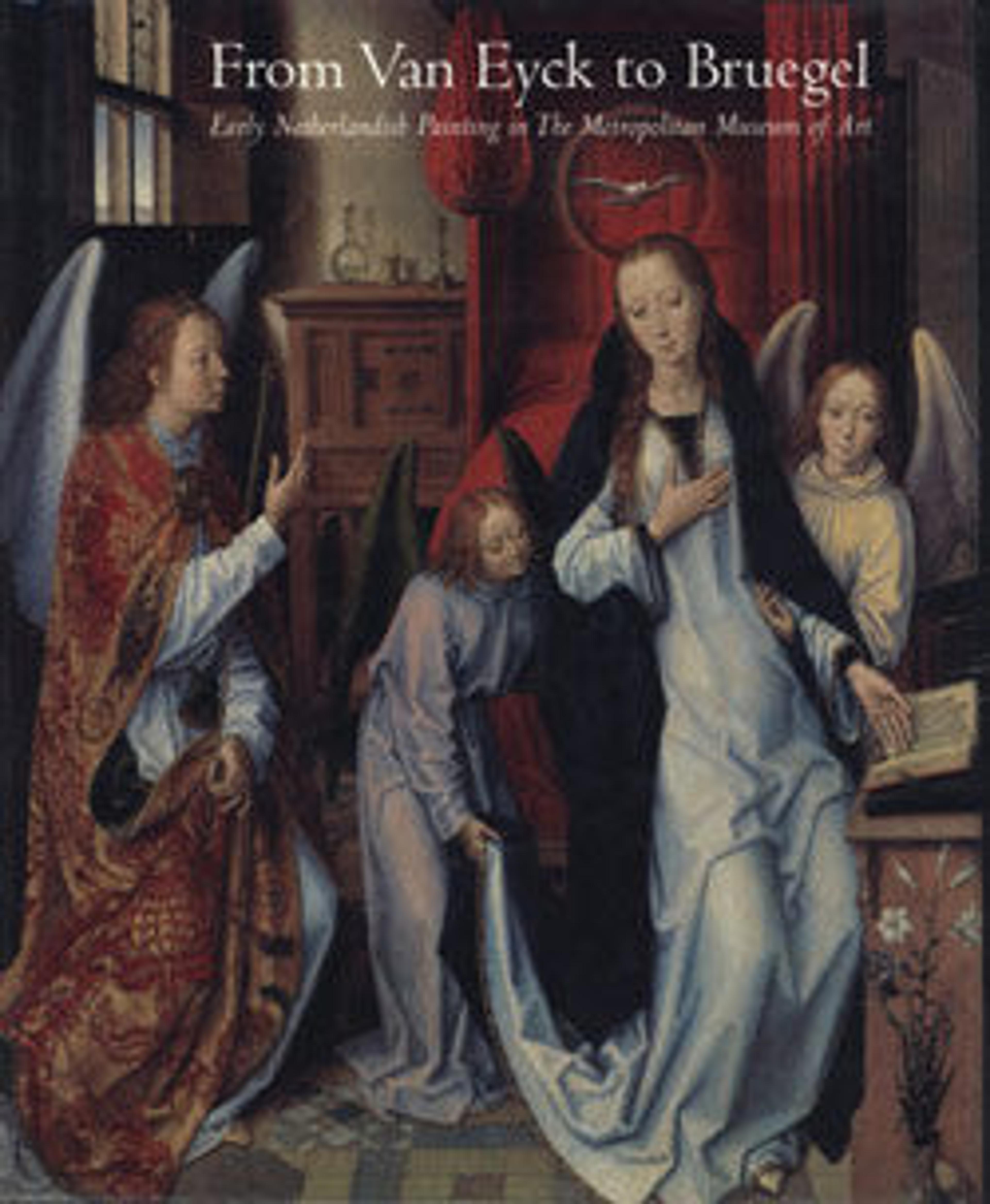

Virgin and Child

Devotional images of the breastfeeding Virgin became extremely popular in fifteenth-century painting, particularly in Bruges, where the Sint-Donaaskerk housed relics of Mary’s hair and milk. This particular version combines venerable elements of the Byzantine icon tradition, like the gold background, with the increased realism and tenderness of contemporary Netherlandish painting. The frame is original, and holes for hinges (now plugged) indicate that the panel was formerly the central element of a triptych.

Artwork Details

- Title: Virgin and Child

- Artist: Follower of Rogier van der Weyden (Master of the Saint Ursula Legend Group, Netherlandish, active late 15th century)

- Date: ca. 1480–90

- Medium: Oil on wood

- Dimensions: Arched top, 22 1/8 x 13 1/2 in. (56.2 x 34.3 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917

- Object Number: 17.190.16

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

2622. Investigations: Virgin and Child, Part 1

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.