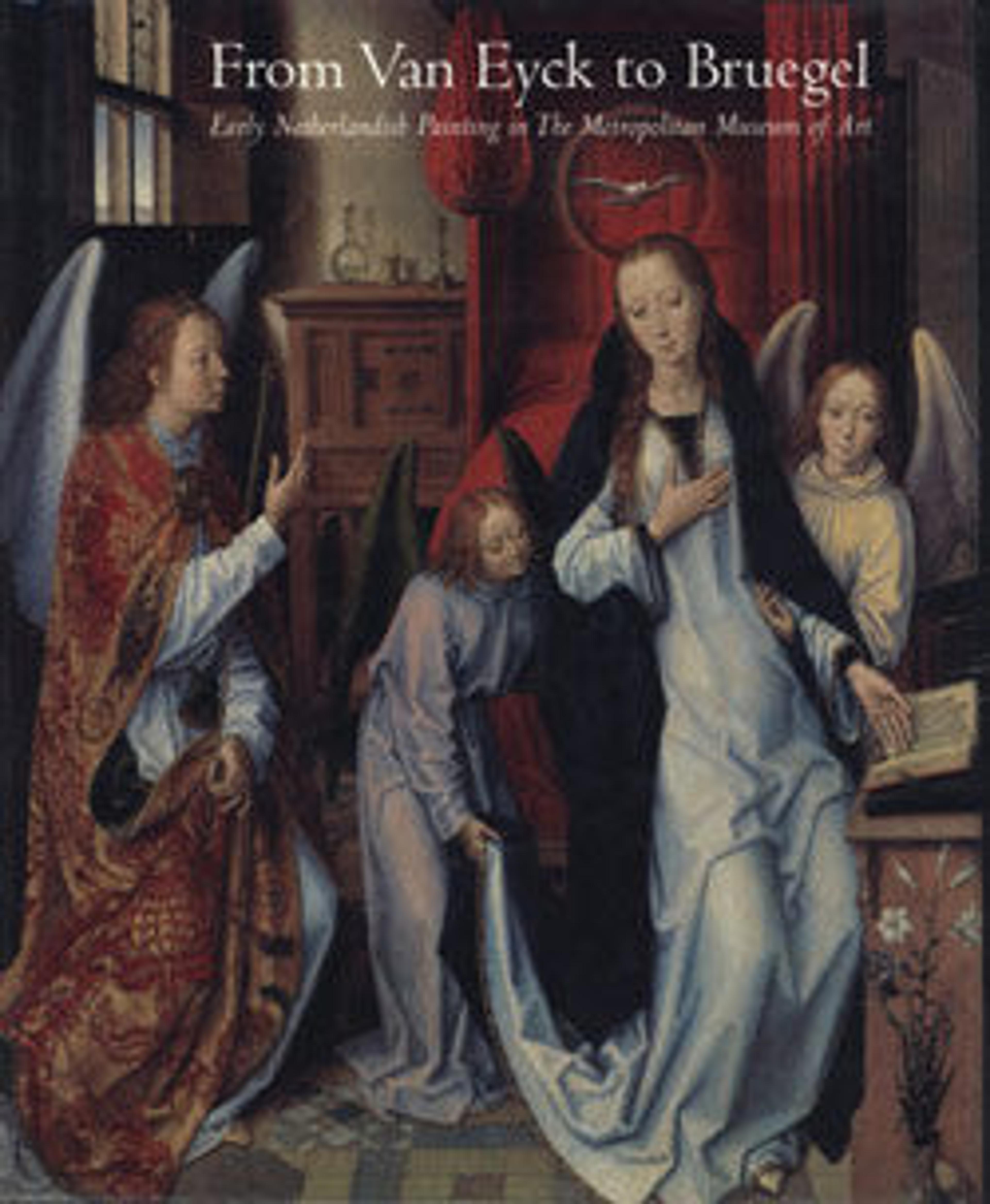

Virgin and Child with Angels

Van Orley probably painted this refined and intimate picture of the Virgin and Child about the time of his appointment in 1518 as official painter to Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands. A courtly Madonna of Humility, the Virgin wears a luxurious fur-trimmed dress and is seated on the ground in the enclosed but spacious garden of her palace. She is accompanied by two singing angels, who are echoed by grisaille angels in heaven. The distant background testifies to the painter’s awareness of the development of landscape painting, and the elaborately ornamented fountain incorporates Italian Renaissance decorative motifs.

Artwork Details

- Title:Virgin and Child with Angels

- Artist:Bernard van Orley (Netherlandish, Brussels ca. 1492–1541/42 Brussels)

- Date:ca. 1518

- Medium:Oil on wood

- Dimensions:33 5/8 x 27 1/2 in. (85.4 x 69.9 cm)

- Classification:Paintings

- Credit Line:Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913

- Object Number:14.40.632

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.