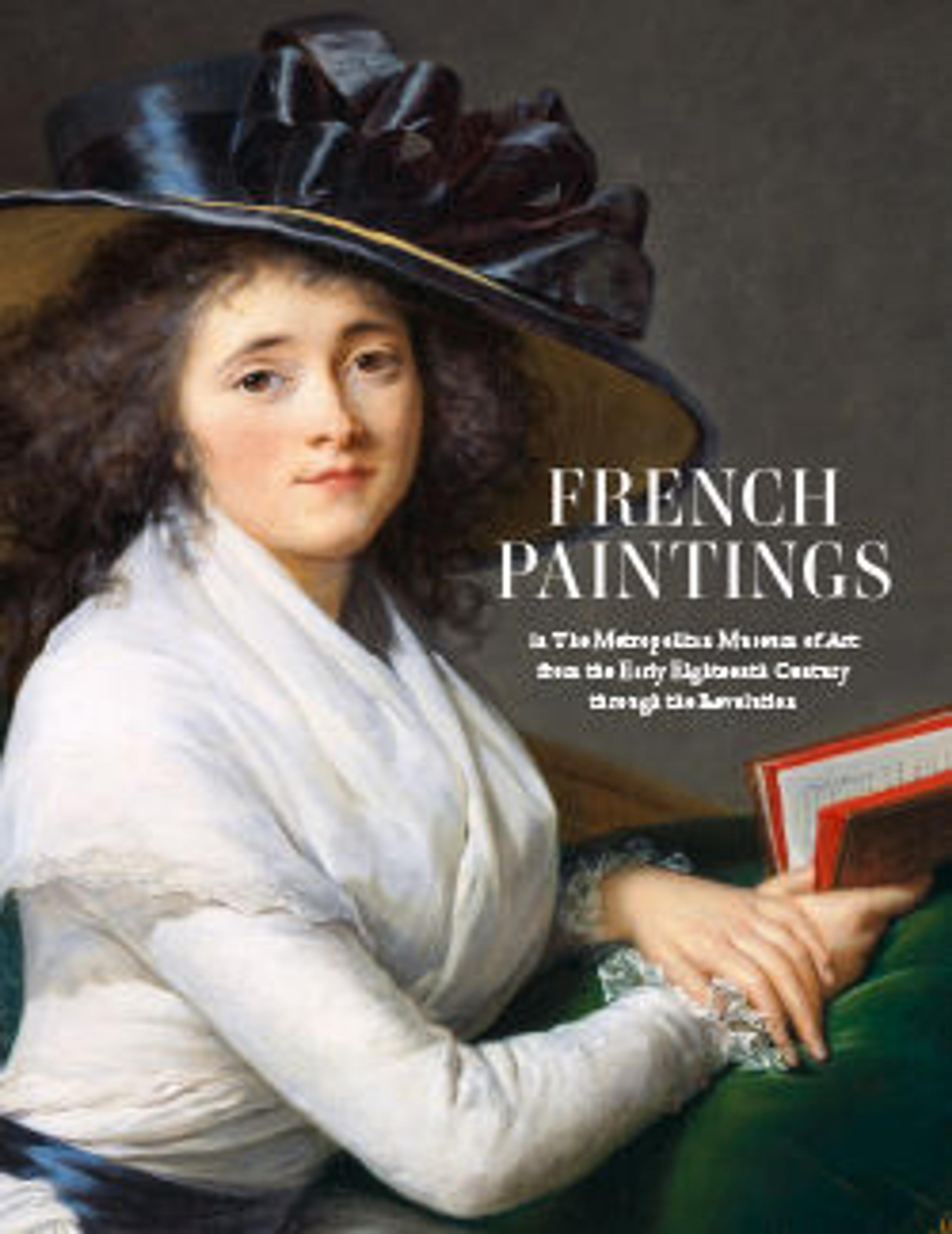

Maria Luisa of Parma (1751–1819), Later Queen of Spain

This portrait of Maria Luisa of Parma, granddaughter of both King Louis XV of France and Philip V of Spain, was sent to Madrid in advance of her marriage to her first cousin, the future Carlos IV of Spain. It is exemplary of formal eighteenth-century court portraits. Painted in Italy for Spanish eyes, it teems with French decorative arts, evidence of Parisian craftsmen’s international preeminence in the period. The bronze clock case is supported by an exoticized elephant, the gold snuffbox is fitted with a miniature portrait of Maria Luisa’s future husband, and the impressive chair comes from a suite of furniture commissioned in Paris by her mother a decade prior.

Artwork Details

- Title: Maria Luisa of Parma (1751–1819), Later Queen of Spain

- Artist: Laurent Pécheux (French, Lyons 1729–1821 Turin)

- Date: 1765

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 90 7/8 x 64 3/4 in. (230.8 x 164.5 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Bequest of Annie C. Kane, 1926

- Object Number: 26.260.9

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

Audio

2259. Maria Luisa of Parma (1751–1819), Later Queen of Spain

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.