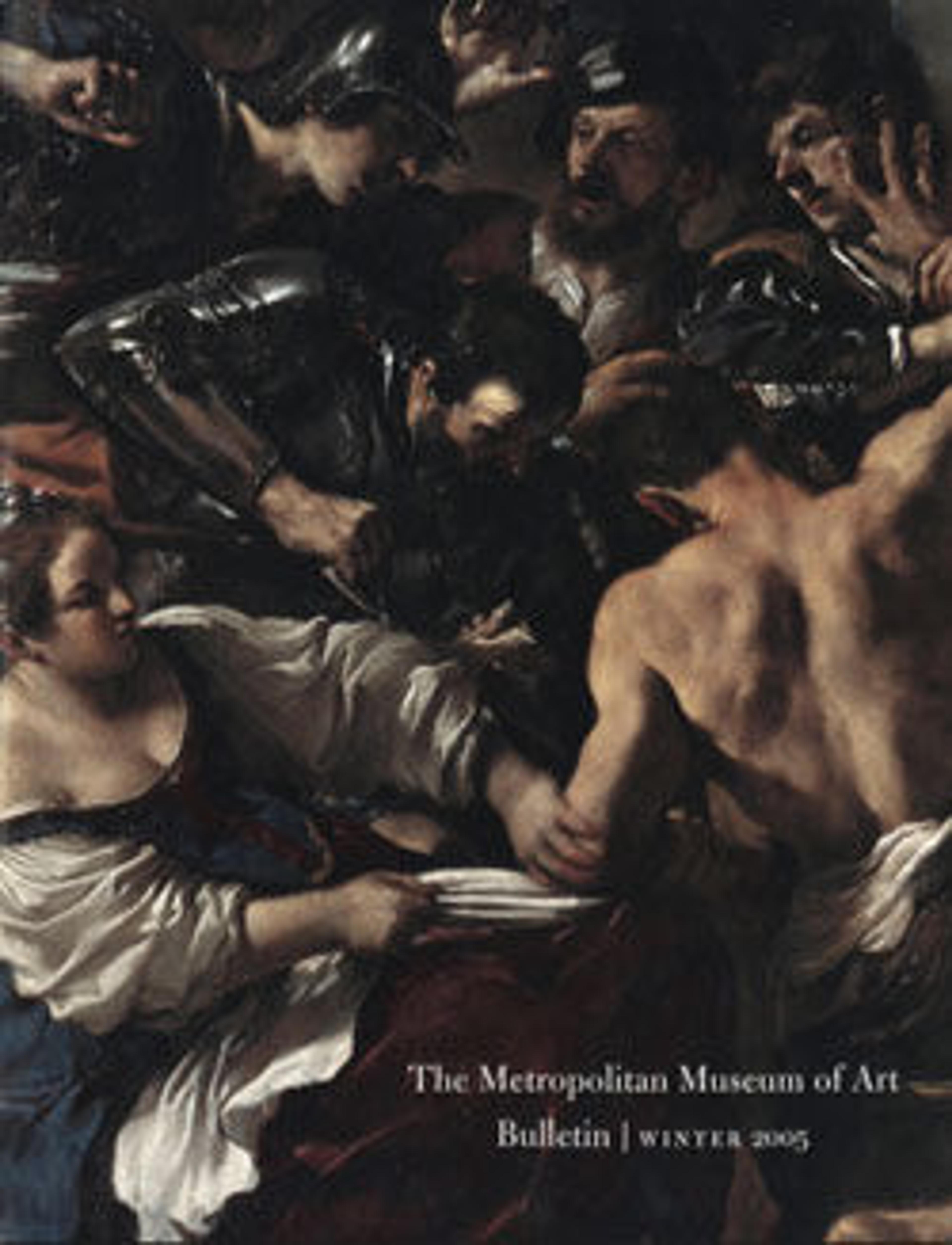

Pilate Washing His Hands

According to the Gospel of Matthew, the Roman governor Pontius Pilate tried to save Christ from death and symbolically washed his hands, stating, “I am innocent of the blood of this righteous person.” Pilate has been given monumental form in this rare depiction of the subject, while Christ is shown in the middle ground being led to the cross. The young African attendant is given a central role, not only in the composition but also through a facial expression that registers the import of Pilate’s action. Preti follows a Renaissance tradition of including such figures, but children of African descent were also familiar to him firsthand. This painting was executed in Malta, an island with a particularly multiracial population due to its centrality in the Mediterranean slave trade, and three enslaved individuals described as “Ethiopian” were recorded in Preti’s household in 1668.

Artwork Details

- Title: Pilate Washing His Hands

- Artist: Mattia Preti (Il Cavalier Calabrese) (Italian, Taverna 1613–1699 Valletta)

- Date: 1663

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 81 1/8 x 72 3/4 in. (206.1 x 184.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan and Bequest of Helena W. Charlton, by exchange, Gwynne Andrews, Marquand, Rogers, Victor Wilbour Memorial, and The Alfred N. Punnett Endowment Funds, and funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, 1978

- Object Number: 1978.402

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.