The Artist: Théodore Chassériau was born at El Limón, near Samanà, on the Carribean island of Hispaniola, on September 20, 1819. The colonial epoch and its aftermath in the Atlantic world are well illustrated by the convergence of Théodore’s paternal and maternal lines. His father, Benoît Chassériau (1780–1840), was the youngest of eighteen children in a family from the French port city La Rochelle. An adventurer, he participated in Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaign from 1798 to 1801, and administered the colony of Saint-Domingue on Hispaniola under French rule from 1802 to 1807; Simón Bolívar (1783–1830) appointed him Minister of the Interior and head of the police at Cartagena, Colombia, in 1813. Théodore’s mother, Marie Madeleine Couret de la Blaquière (1791–1866), whom Benoît married in 1806, was the daughter of a Frenchman from Hispaniola’s plantation-owning class; her extended family included enslaved Black men and women. At the time of Théodore’s birth in late 1819, Hispaniola’s eastern territory, Santo Domingo, or Saint Domingue (present-day Dominican Republic) was battling Spain for independence. Simultaneously, its western region, Haiti, which had achieved independence from France in 1804, was fighting to assert its dominion over all of Hispaniola. Amidst this political instability the Chassériau family moved to Paris in 1820.

Théodore was eleven years old in 1830, when his precocious talent as a draftsman gained him entry to the studio of painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) as his pupil. The ensuing decade was formative for Chassériau. Ingres was made director of the French Academy in Rome in 1834; Chassériau began to exhibit paintings, both historical subjects and portraits, at the Paris Salon in 1836; and, in 1840–41, he followed Ingres to Rome (see The Met

2002.291). These developments laid the groundwork for Chassériau’s own contribution to his extended family’s engagement with a globalizing France.

Chassériau and Algeria: In 1844, Chassériau was one of a number of artists to make portrait studies of Ali ben Hamet, Caliph of Constantine in French-occupied Algeria, during his visit to Paris. Ali subsequently invited Chassériau to paint him, resulting in the spirited equestrian group portrait exhibited at the Salon of 1845 (128 x 102 in., 325 x 259 cm, Château de Versailles). Critics compared the painting favorably to another picture on view in the Salon that year, Eugène Delacroix’s more static but even larger

Moulay Abd-Er-Rachman, Sultan of Morocco, Leaving His Palace at Meknès, Surrounded by his Guards and Principal Officers (148 1/2 x 134 in., 377 x 340 cm, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse). Whereas Delacroix had contemplated his subject since witnessing it in 1832, it was Ali ben Hamet’s commission that prompted Chassériau’s first and only visit to North Africa: to Algeria, as Ali’s guest, in 1846.

France’s conquest of Algeria in 1830 precipitated the diplomatic mission to neighboring Morocco that Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was invited to join, quite by surprise, in 1832. His experiences there, the extensive studies with which he documented them, and the paintings and watercolors they inspired afterward, in France, may all be understood as foundational to Chassériau’s Algerian trip a decade and a half later.

Chassériau left Paris on May 3, 1846, arriving in Philippeville on May 10. In the 1830s, the French had developed the port of Philippeville (ancient Rusicade, present-day Skikda) to serve the city of Constantine, about thirty-five miles inland. His sojourn in Constantine lasted just over one month, from May 11 to June 13. From there the painter traveled via Oran to Algiers, where he embarked in early July, landing at Marseilles before returning to Paris.

Théodore wrote to his brother Frédéric from Constantine: “This land is very beautiful and very new. I am living in the Thousand and One Nights. I think I can really get something from it for my art. I work and I look. . . .” (May 13, 1846). He also wrote: “This is supposed to be the only truly Arabian city left in this country, and so I am making the most of it” (May 23, 1846). To drive home Constantine’s exoticism, he wrote again shortly afterward: “It is the only truly Arabian place left in Africa” (June 4, 1846). Deeper context is conveyed by another letter to Frédéric, written shortly after he left the city: “I have seen some very curious, primitive, and dazzling things, strange and touching. In Constantine, which is situated atop high mountains, one can see the Arab race and the Jewish race, as they were on their first day [i.e., from time immemorial]. I will tell you all about this and you will see many studies: all that can possibly be done when seeing so many different things passing before one’s eyes in so short a time. I have taken notes and, with my memory, think I will not forget anything” (June 13, 1846).

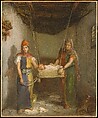

First Treatment of the Subject, June or July 1846: The first source for

Scene in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine is a summary sketch that Chassériau made on the spot (pencil on pink paper, 12 11/16 x 12 7/16 in., 32.3 x 31.6 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 25519 recto). The drawing depicts a woman standing frontally, rocking a baby in its cradle, which is suspended from a wood-beamed ceiling in a small, ill-defined interior space, perhaps an alcove off a larger room. She casts a shadow on the left wall. To her right are the head and shoulders of a woman seen in profile, supine, with no other indication as to her actual position within the space; beneath her two babouches, noted as casually perpendicular to one another, lie on the floor. On the left wall is the faint indication of a niche and, on the right, a small window. A cloth hanging is indicated by a mere jot. (For a sketch similar in theme and equivalent in its economy, see

Jewish Woman of Algiers Seated on the Ground, The Met

64.188).

Second Treatment of the Subject, Late Summer–Early Fall 1846: After he returned to France, Chassériau developed the scene into a highly finished painting, executed in gouache on paper (21 3/4 x 15 1/4 in, 55 x 38.5 cm, private collection), which would serve as a second step on the way to The Met canvas. Chassériau retained all the elements of the pencil drawing, but he endowed them with substance and color and added details.

With her right hand, the standing woman transferred from the sketch now holds the end of a slack cord attached to the simple cradle while pushing the cradle back, gently, with her left. The cradle is shown to be assembled from rough-hewn lengths of wood joined at the corners. To its right, there is a second standing woman, who clings to one of the supporting ropes as she gazes at the sleeping infant. In the foreground a third, kneeling, woman, shown in profile, also admires the child. One can only speculate whether the two women at the right of the gouache were present when Chassériau first glimpsed the scene (signified by the wisp of a profile in the Louvre drawing) or if he invented them as he developed the composition. Vague circular forms in the Louvre sketch are now seen as an irregular stone pavement. Entirely new are the geometrically patterned shutters, barred shut, extending the full width of the narrow back wall.

The modest scene of Jewish domestic life depicted in the gouache was made for a lavish album commissioned by the princes and princesses of the royal Orléans family. It was their gift to the Spanish-born Marie-Louise Fernande de Bourbon, duchesse de Montpensier (1832–1897), to welcome her as their sister-in-law upon her marriage to their youngest brother, Antoine Marie Philippe Louis d’Orléans (1824–1890), on October 10, 1846. The precious book featured more than forty works on paper by leading artists, including not only Ingres and Delacroix, but also Adrien Dauzats, Paul Delaroche, Paul and Hippolyte Flandrin, Paul Huet, Antoine-Louis Barye, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps, Ary Scheffer, Horace Vernet, and François-Marius Granet. Chassériau’s choice of subject was appropriate for newlyweds, and its cultural context was undoubtedly chosen to flatter the young groom following his recent military service in Algeria.

The Painting, 1851: The Met painting is dated 1851, perhaps five years after Chassériau’s visit to Constantine, but nothing is known about the circumstances of its production, including whether it was made on commission or for the open market. It is not much larger than the gouache, but it is proportionally wider, and formally bolder. Only the two standing figures remain on either side of the baby. And, curiously, although the space is awkward in all three renditions of the scene, it is clear that this reflects the artist’s intention, since he could have constructed it otherwise had he wished. Chassériau very likely meant for this feature to convey the strangeness and primitiveness to which he referred in the letter to his brother quoted above. In summoning those qualities—as he originally described them in letters to his brother—onto the canvas, the painter now employed the material of paint and technical means of the brush to express the “dazzling” effects that he described in Constantine.

Chassériau abandoned the attenuated, elegant figures that he had rendered in gouache with conscious finesse in favor of more full-bodied counterparts depicted with a loaded brush and greater painterliness, and with color playing a more assertive role. Both women now wear dresses divided vertically into two panels, such that the composition reads, from left to right, as dominated by wide stripes of saturated blue, yellow, orange, and green punctuated by islands of gold. The corners at the back of the room in the gouache have been transformed into a continuous curve, so that the light admitted by the window high on the right side illuminates its roughly plastered surface gradually, casting the woman on the left into higher relief than her counterpart on the right.

In The Met picture, details recede into supporting but no less essential roles than the major parts. For example, the woman on the right stands with one hand on either side of the cradle, while the woman on the left now holds the rope loosely between her hands. That rough cord doubles back, and does so again by means of the fine shadow it casts against the blue and yellow dress, standing in sharp contrast to the elaborate silver buckle reflecting light just above. In another example, the diaphanous scarves are rendered in secondary tones that register equally as what they represent and as pigmented strokes of paint that converge, seemingly casually, at the neck. Witness how the scarf at the left drifts outward from the woman’s body as if catching a breeze, the gauze catching the light from the window as the gold flecks reflect it, interrupting the shadow behind the woman herself. The canniness of these details is convincing corroborating evidence that the infant sleeping between the two women is now the focal point of the picture, not only by virtue of its role in the subject, but also its centrality to the composition, and because the caretakers’ purposeful silence and stillness ensure its imperturbability.

Chassériau’s career was successful but brief. He died at thirty-seven, on October 8, 1856, about five years after painting

Scene in the Jewish Quarter of Constantine.

Asher Ethan Miller 2025

Note: The information on which this entry is based, including citations to letters, is Miller 2002, as well as the book of which it is part (see References).