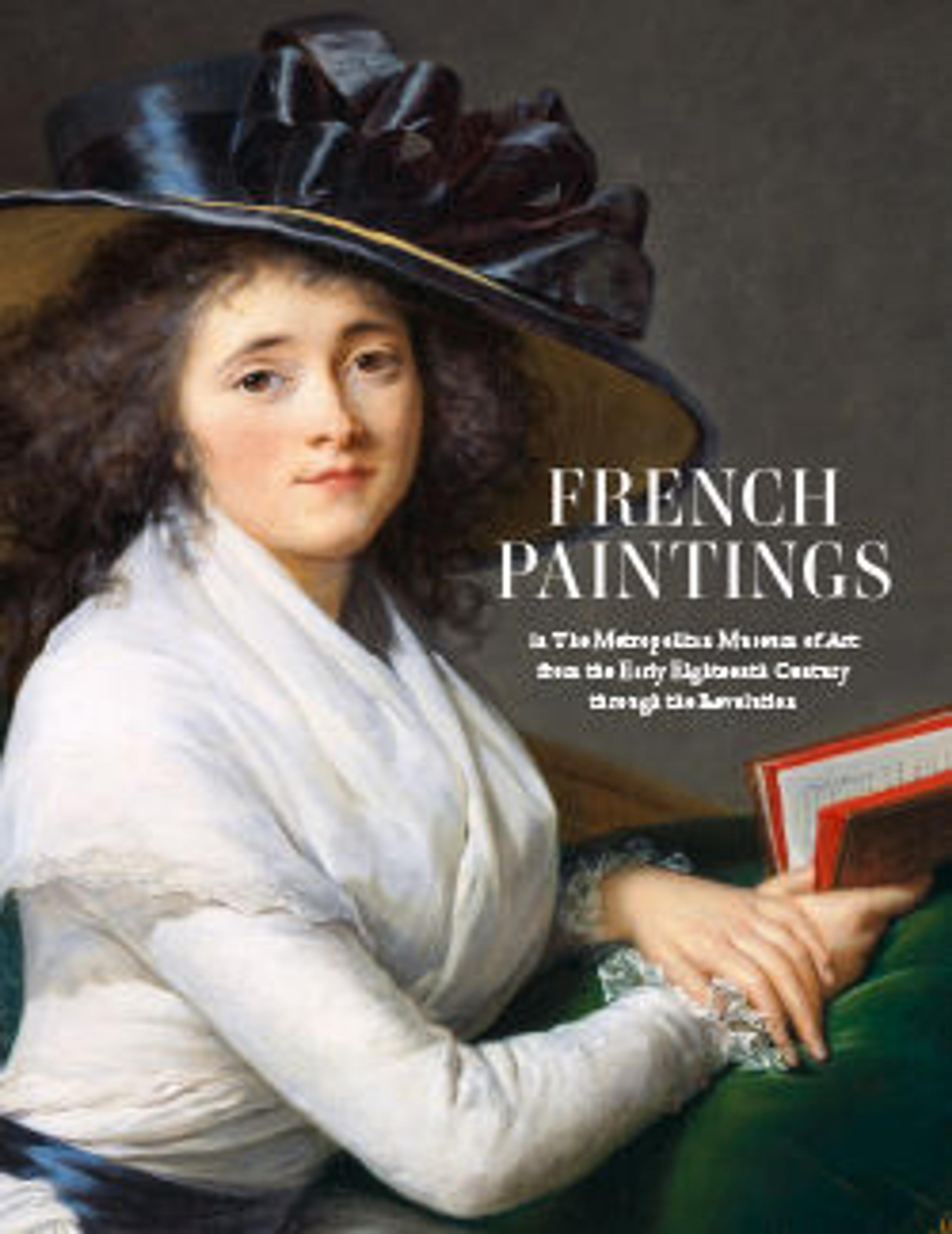

Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord (1761–1835)

Gérard, a student of Jacques Louis David, was official painter to Empress Joséphine; the sitter was a celebrated beauty, captured in Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s youthful portrait from 1783, also at The Met. In 1802, her affair with the statesman Talleyrand was so scandalous that Napoleon demanded they marry; neither was particularly faithful, however, and, by the time this portrait was painted, they had separated. Thus, this is not a pendant to either of the two portraits of Talleyrand at The Met. Gérard’s brush revels in details of the highly fashionable interior: contrasting sun and fire light from the novel chimney installed beneath a window, the diaphanous dress, and the paisley shawl—a modish accessory, but also a nod to the sitter’s birth near Pondicherry, in colonial India.

Artwork Details

- Title: Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord (1761–1835)

- Artist: baron François Gérard (French, Rome 1770–1837 Paris)

- Date: ca. 1804

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 88 7/8 x 64 7/8 in. (225.7 x 164.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Wrightsman Fund, 2002

- Object Number: 2002.31

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.