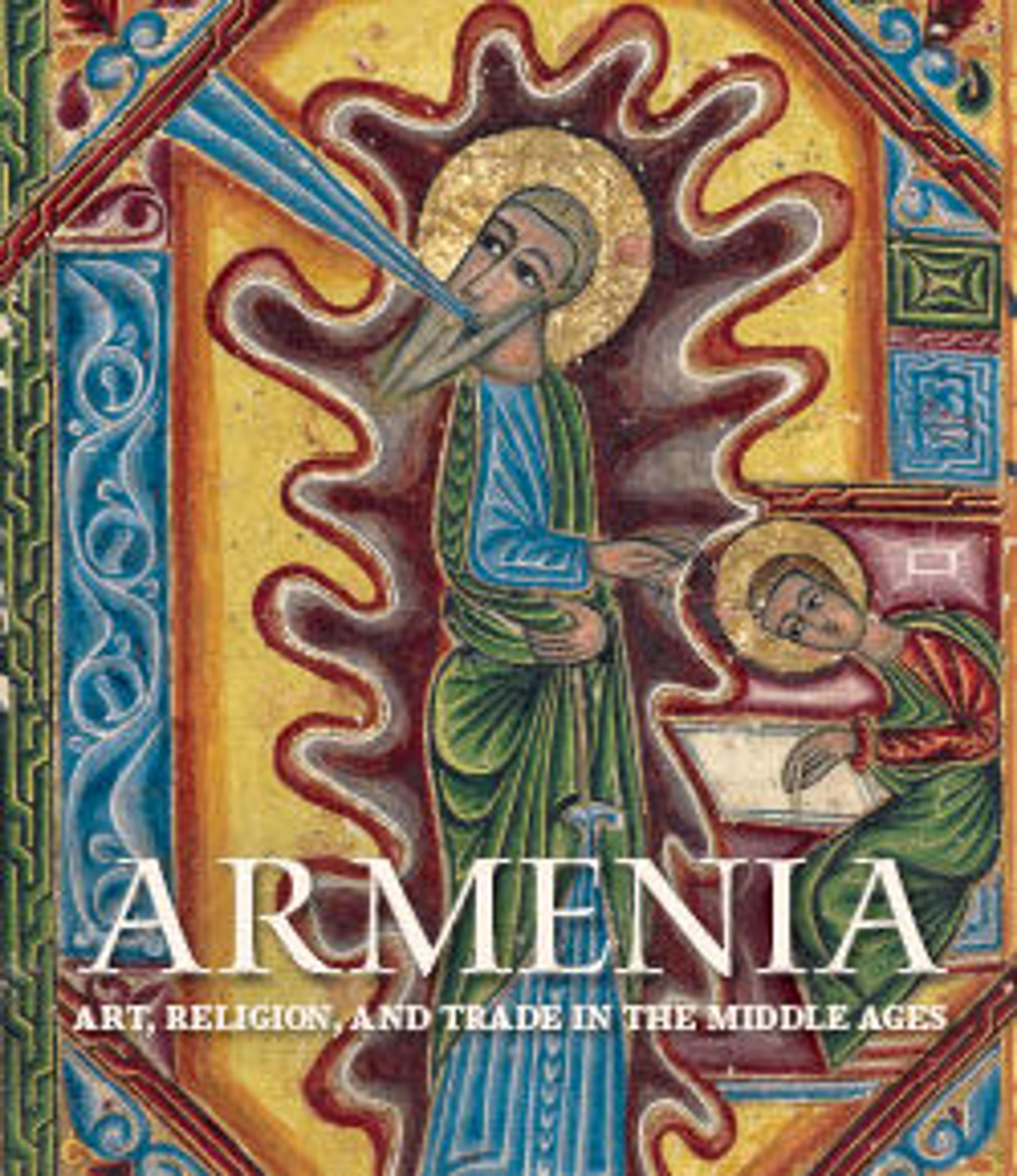

Armenian Gospel with Silver Cover

These jeweled, enameled, and gilt-silver repoussé covers for a gospel are examples of the work produced in the late seventeenth-century Armenian silversmith workshop of Kayseri. Both front and back cover are signed, informing us that they were made in Kayseri in 1691 by Astuatsatur Shahamir. The central image on the front cover depicts the Adoration of the Shepherds, and above, the magi following the star. Amid angels, the banner in the sky proclaims, "Glory to God in the highest and on Earth peace." The same composition of shepherds appears on two sets of gospel covers made in Kayseri by M. Karapet Malkhas, one dated 1671 (Mekhitarist Library, Vienna, MS 416) and the other dated 1691 (present location unknown). On the back is the Resurrection, showing Christ in a mandorla holding a bannered cross, surrounded by baroque cherubs and clouds. The green velvet spine is decorated with six garnets and numerous glass or crystal gems arranged in a diamond pattern. These covers were attached to a gospel copied and illuminated by a thirteenth-century scribe named Grigor, possibly from Cilicia.

Artwork Details

- Title: Armenian Gospel with Silver Cover

- Date: manuscript: 13th century; cover: dated 1691

- Geography: Made in present-day Turkey [Cover], Kayseri. Made in present-day Turkey [Manuscript], probably Cilicia

- Medium: Manuscript: ink and tempera on parchment

Cover: gilded silver repoussé, with colored enamels, jewels, and imitation gems - Dimensions: Pages: H. 10 in. (25.4 cm)

W. 6 3/4 in. (17.1 cm)

Binding: H. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm)

W. 7 3/8 in. (18.7 cm)

Approx. opening with cradle: H. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm)

W. 13 3/4 in. (34.9 cm)

D. 8 in. (20.3 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1916

- Object Number: 16.99

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.