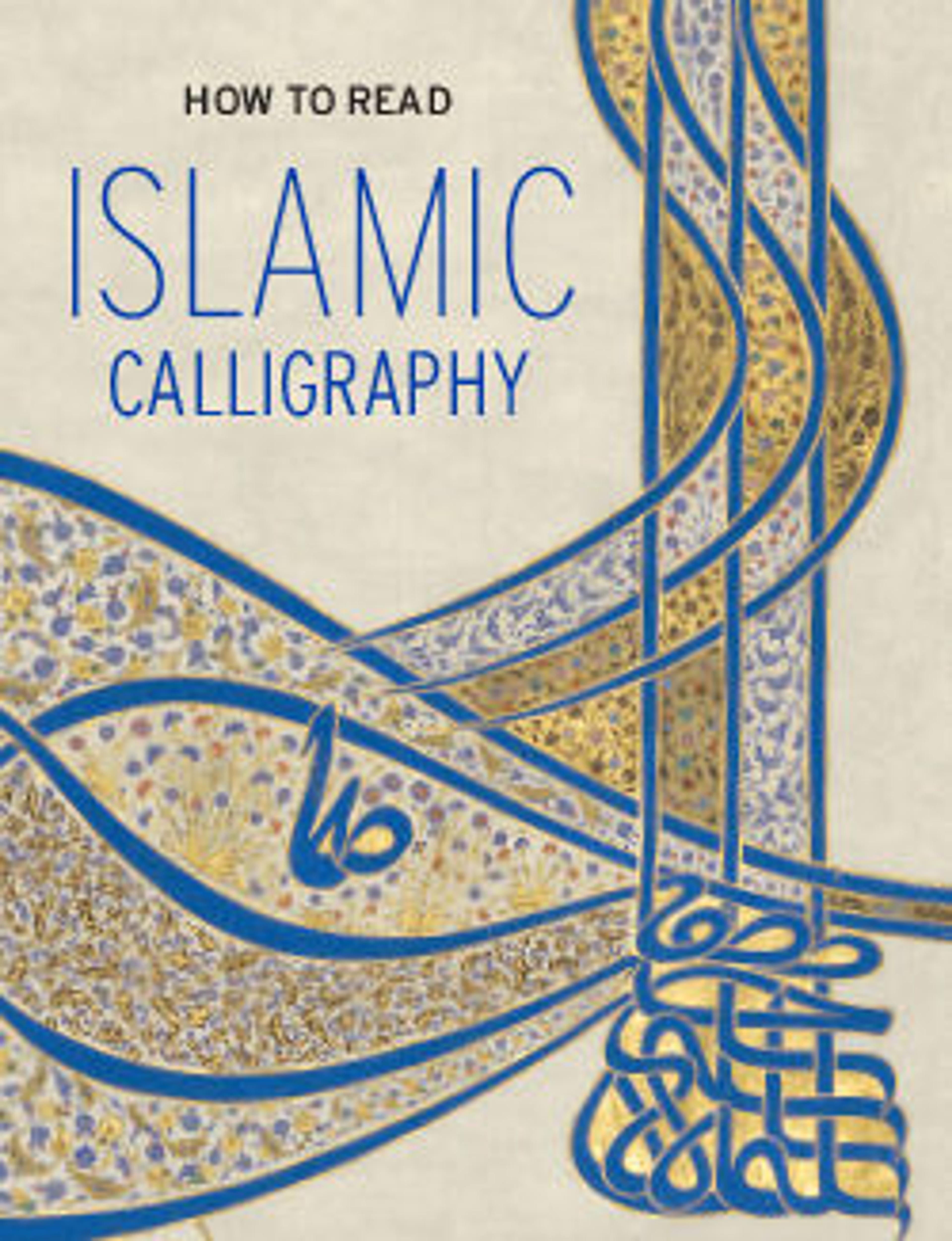

Calligraphic Galleon

The hull of this sailing ship comprises the names of the Seven Sleepers and their dog. The tale of the Seven Sleepers, found in pre-Islamic Christian sources, concerns a group of men who sleep for centuries within a cave, protected by God from religious persecution. Both hadith (sayings of the Prophet), and tafsir (commentaries on the Qur'an) suggest that these verses from the Qur'an have protective qualities.

Artwork Details

- Title: Calligraphic Galleon

- Calligrapher: 'Abd al-Qadir Hisari (Turkish)

- Date: dated 1180 AH/1766–67 CE

- Geography: Made in Turkey

- Medium: Ink and gold on paper

- Dimensions: H. 19 in. (48.3 cm)

W. 17 in. (43.2 cm) - Classification: Codices

- Credit Line: Louis E. and Theresa S. Seley Purchase Fund for Islamic Art and Rogers Fund, 2003

- Object Number: 2003.241

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.