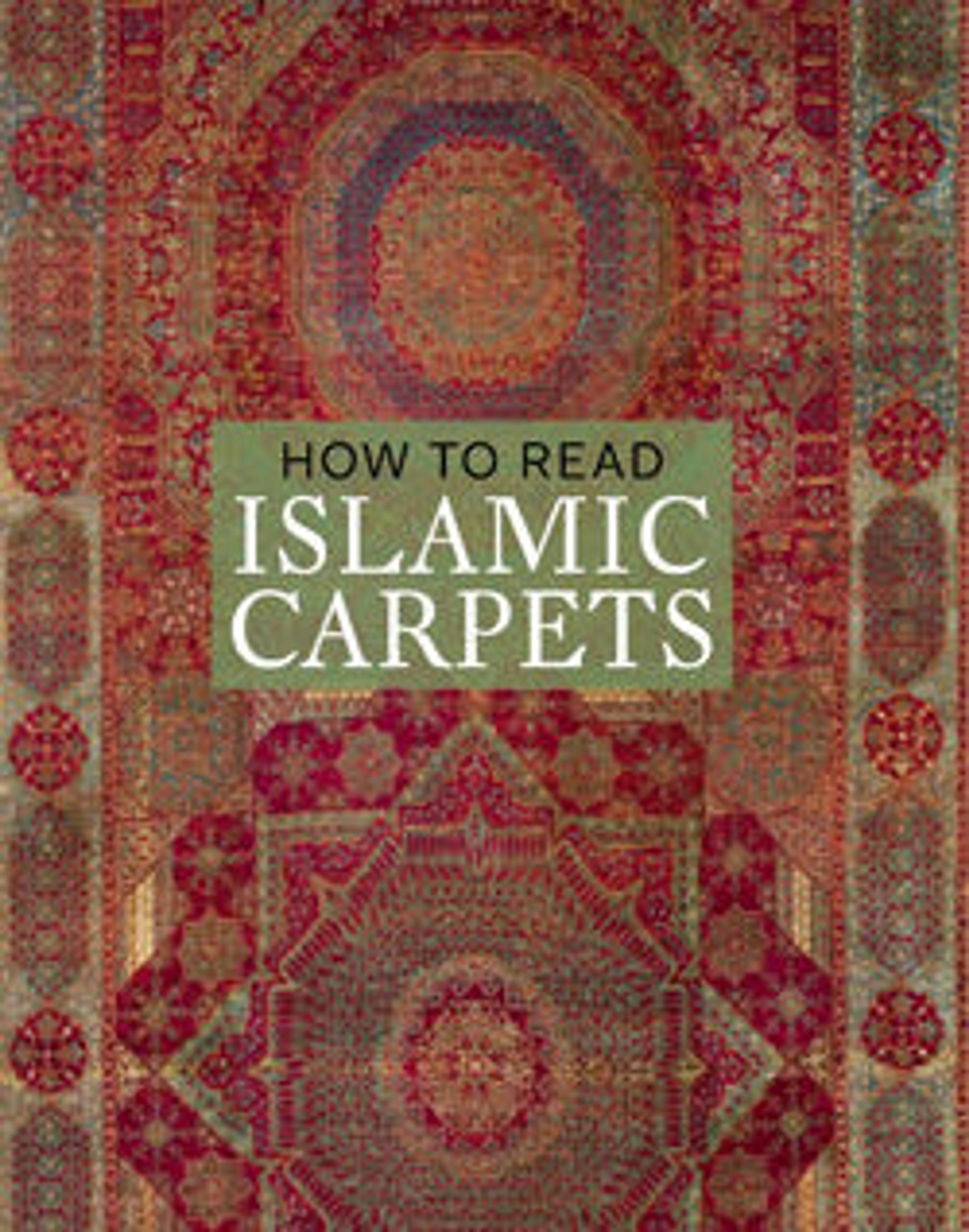

Ottoman Court Carpet

This splendid carpet, with feathery leaves, stylized lotus flowers, and tightly curled cloud‑band scrolls, displays characteristics associated with a group of carpets of debated provenance. While the wool and weaving methods of this group are akin to carpets woven in Egypt, their designs probably were produced in Istanbul. Documents reveal that on at least one occasion in 1585, the Ottoman sultan Murad III requested that a number of Cairene weavers, along with a quantity of Egyptian wool, be brought to the court in Istanbul. Such interactions may explain the unexpected combination of materials, technique, and design found in these carpets.

Artwork Details

- Title: Ottoman Court Carpet

- Date: late 16th–17th century

- Geography: Attributed to Egypt

- Medium: Wool (warp, weft and pile); asymmetrically knotted pile

- Dimensions: Rug:

Gr. L. 226 1/4 in. (574.7 cm)

Gr. W. 112 in. (284.5 cm)

L. of proper right:

L. 223in. (566.4 cm)

L. of proper left:

L. 224in. (569 cm)

Tube:

H. 131 1/4 in. (333.4 cm)

Diam. 11 in. (27.9 cm) - Classification: Textiles-Rugs

- Credit Line: Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941

- Object Number: 41.190.257

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

Audio

6648. Overview: Ottoman Court Carpets

0:00

0:00

We're sorry, the transcript for this audio track is not available at this time. Please email info@metmuseum.org to request a transcript for this track.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.