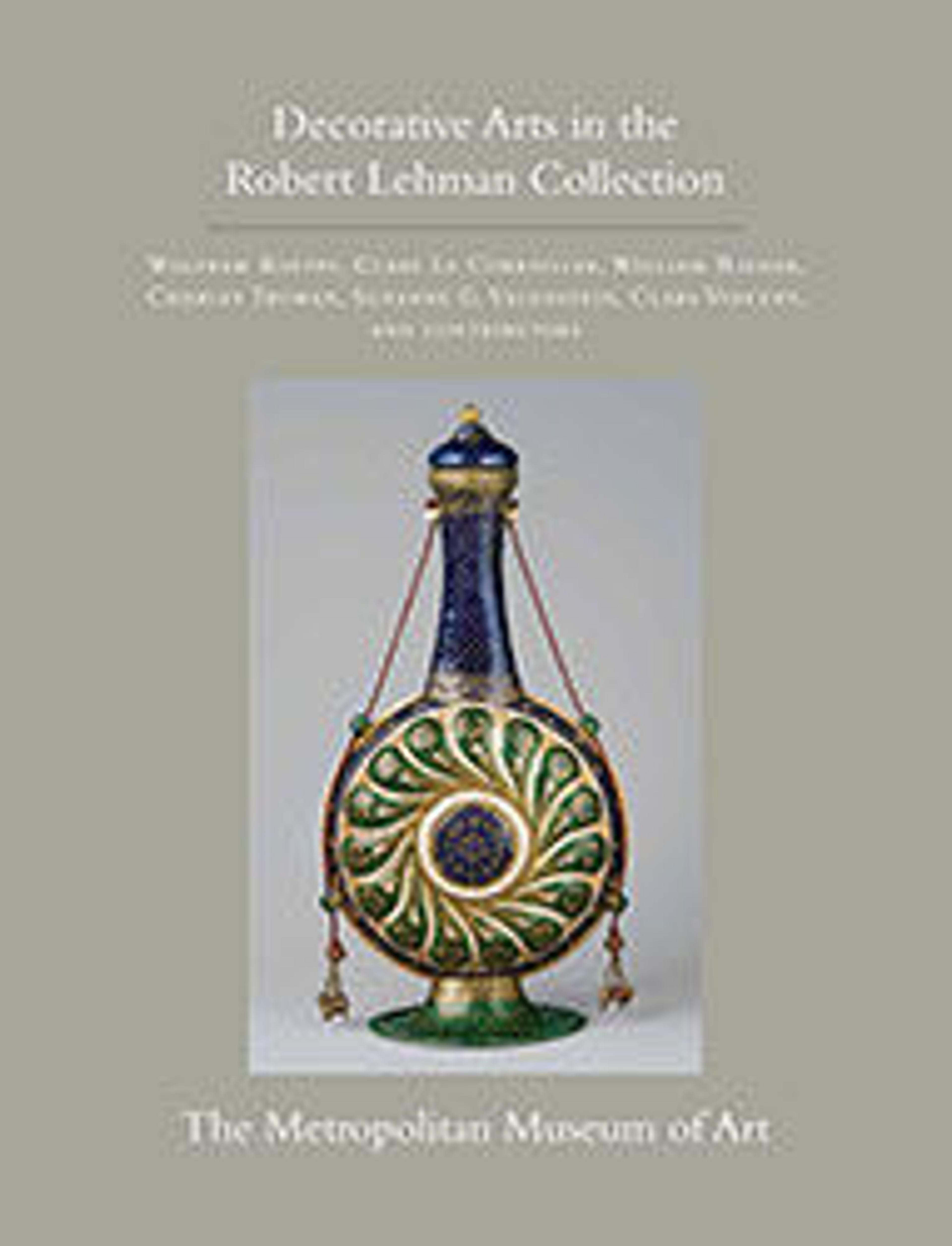

Paternoster Pendant with the Virgin and Child (obverse) and the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate (reverse)

Pendants of this type were designed to hang from a paternoster or rosary (a string of prayer beads), a devotional object that became popular in the fifteenth century, particularly in the Netherlands. They functioned as a visible sign of the wearer's piety, as well as a fashion accessory. Despite their diminutive size, the Virgin and Child on the cameo obverse exhibit a monumentality reminiscent of fifteenth-century Burgundian sculpture. Employing a different medium in an unusual combination of techniques, the reverse is executed in basse-taille, whereby the design is worked into a bed of silver coated with a layer of translucent enamel. The rich glowing colors achieved through this technique recall those of stained glass.

Few of these pendants of Franco-Burgundian origin survive, and this example in the Robert Lehman Collection is of unsurpassed quality and importance. The use of precious materials, the inclusion of Saint Anne (who was particularly venerated in Burgundy in the fifteenth century), the style of the figures, and the consummate craftsmanship of this object suggest that it was manufactured in a Burgundian court workshop, though the identity of the original owner is unknown. It shows considerable rubbing, no doubt from devotional handling.

Few of these pendants of Franco-Burgundian origin survive, and this example in the Robert Lehman Collection is of unsurpassed quality and importance. The use of precious materials, the inclusion of Saint Anne (who was particularly venerated in Burgundy in the fifteenth century), the style of the figures, and the consummate craftsmanship of this object suggest that it was manufactured in a Burgundian court workshop, though the identity of the original owner is unknown. It shows considerable rubbing, no doubt from devotional handling.

Artwork Details

- Title: Paternoster Pendant with the Virgin and Child (obverse) and the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate (reverse)

- Date: ca. 1440–50; 19th or 20th century

- Culture: Flemish or Burgundian, and Western European

- Medium: Sardonyx, enameled gold, and silver

- Dimensions: 2 3/4 x 1 in. (7 x 2.5 cm)

- Classifications: Jewelry, Precious Metals and Precious Stones

- Credit Line: Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

- Object Number: 1975.1.1522

- Curatorial Department: The Robert Lehman Collection

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.