Cassone

Cassone is the term given to large decorated chests made in Italy from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries. Next to the marriage bed, cassoni were cherished in wealthy Renaissance households, for they held clothing, precious fabrics, and other valuables. Often commissioned by the groom in marriage, a cassone was prominently carried in the nuptial procession, laden with the dowry of his new bride. In the fifteenth century, whole workshops were given over to the manufacture and decoration of cassoni.

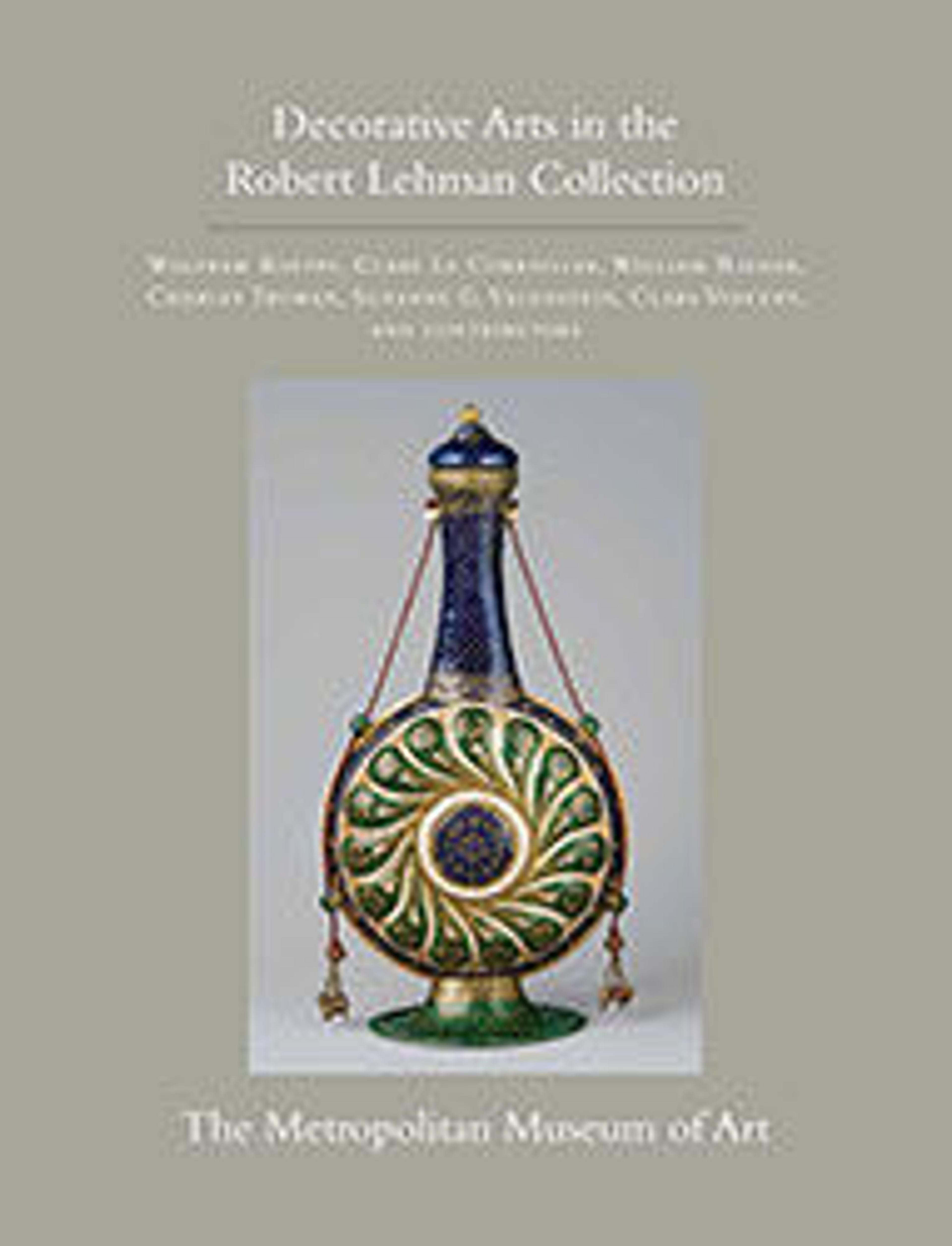

Italian Renaissance workshops produced cassone front panels painted with episodes from classical or biblical history and mythology, evidently felicitous narratives for the newly married. Other cassone designs featured ornamental and figural carvings and inlays of various kinds, as in this splendid example from the Robert Lehman Collection. This cassone is embellished with a pattern of facing eagles, two armorial shields referencing the families united in marriage, and a fleurs-de-lis motif on the sides. These raised decorations were modeled in gesso on the wooden base with the use of a mold and then gilded.

Italian Renaissance workshops produced cassone front panels painted with episodes from classical or biblical history and mythology, evidently felicitous narratives for the newly married. Other cassone designs featured ornamental and figural carvings and inlays of various kinds, as in this splendid example from the Robert Lehman Collection. This cassone is embellished with a pattern of facing eagles, two armorial shields referencing the families united in marriage, and a fleurs-de-lis motif on the sides. These raised decorations were modeled in gesso on the wooden base with the use of a mold and then gilded.

Artwork Details

- Title: Cassone

- Date: ca. 1425–50

- Culture: Italian (Tuscany, Florence or Siena)

- Medium: Pinewood and poplar, gesso, partly gilded, form molded, and painted.

- Dimensions: H. 51.4 cm, W. 149.2 cm.

- Classification: Woodwork-Furniture

- Credit Line: Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

- Object Number: 1975.1.1938

- Curatorial Department: The Robert Lehman Collection

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.