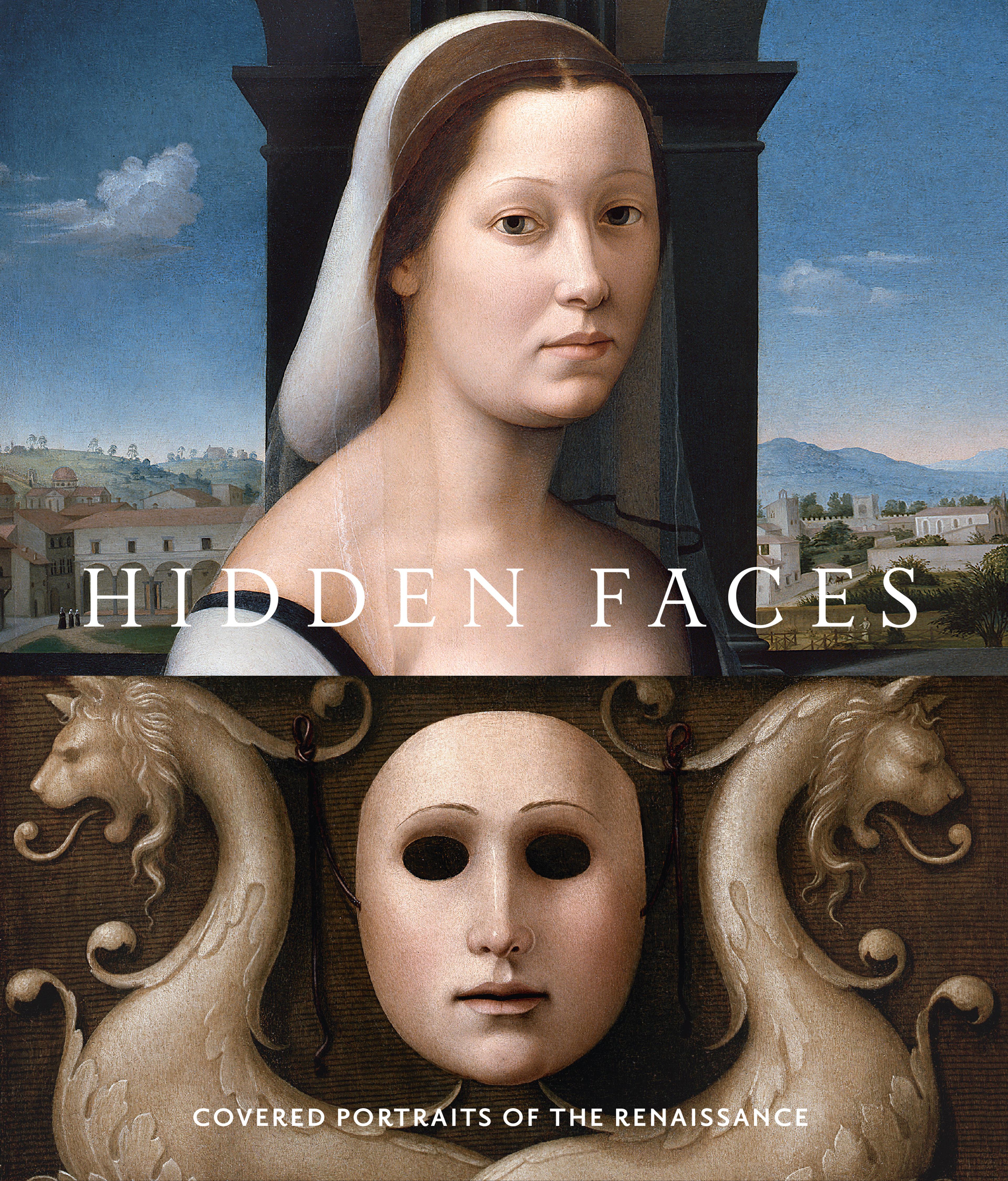

Tabernacle mirror frame

A myriad of meanings, both positive and negative, were attached to mirrors in the Renaissance. Symbols of vanity, voluptuousness, deceit, humility, and pride, mirrors were also associated with prudence, a virtue. Venus, goddess of love, frequently looked at her own comely reflection in a looking glass. By the sixteenth century, the mirror was a codified attribute of female beauty, seen, for example, in Cesara Ripa's 1593 Iconologia with the personification of Bellezza Feminile (Feminine Beauty).

Renaissance mirrors were often concealed behind curtains or shutters, which served to protect the fragile glass. This handsome example is exceptional in having not one but two sliding shutters: the mirror, behind the top shutter, is mounted in a second inner shutter that could be pulled open to one side (the shell-shaped volutes served as handles). The shallow rebate behind the second secret shutter undoubtedly contained an illicit image, probably a portrait of a mistress or lover or an erotic scene, that only the mirror's owner was privileged to behold. Painted mistress portraits were frequently concealed behind shutters or curtains in the sixteenth century and could be revealed only by an actively engaged voyeur—a convention that served to heighten the erotic content of the image by arousing desire and underscoring the forbidden aspect of the subject. The maker of this frame transferred such conceit to this innocent household object, whose owner went to unusual lengths to safeguard his secret.

Renaissance mirrors were often concealed behind curtains or shutters, which served to protect the fragile glass. This handsome example is exceptional in having not one but two sliding shutters: the mirror, behind the top shutter, is mounted in a second inner shutter that could be pulled open to one side (the shell-shaped volutes served as handles). The shallow rebate behind the second secret shutter undoubtedly contained an illicit image, probably a portrait of a mistress or lover or an erotic scene, that only the mirror's owner was privileged to behold. Painted mistress portraits were frequently concealed behind shutters or curtains in the sixteenth century and could be revealed only by an actively engaged voyeur—a convention that served to heighten the erotic content of the image by arousing desire and underscoring the forbidden aspect of the subject. The maker of this frame transferred such conceit to this innocent household object, whose owner went to unusual lengths to safeguard his secret.

Artwork Details

- Title: Tabernacle mirror frame

- Artist: Unknown (Italian, Ferrara)

- Date: 1540–60

- Culture: Italian, Florence(?)

- Medium: Walnut

- Dimensions: Overall: 16 5/16 × 15 3/16 in. (41.5 × 38.5 cm)

Sight: 7 1/2 × 5 7/8 in. (19 × 15 cm) - Classification: Frames

- Credit Line: Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

1975.1.2090 - Object Number: 1975.1.2090

- Curatorial Department: The Robert Lehman Collection

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.