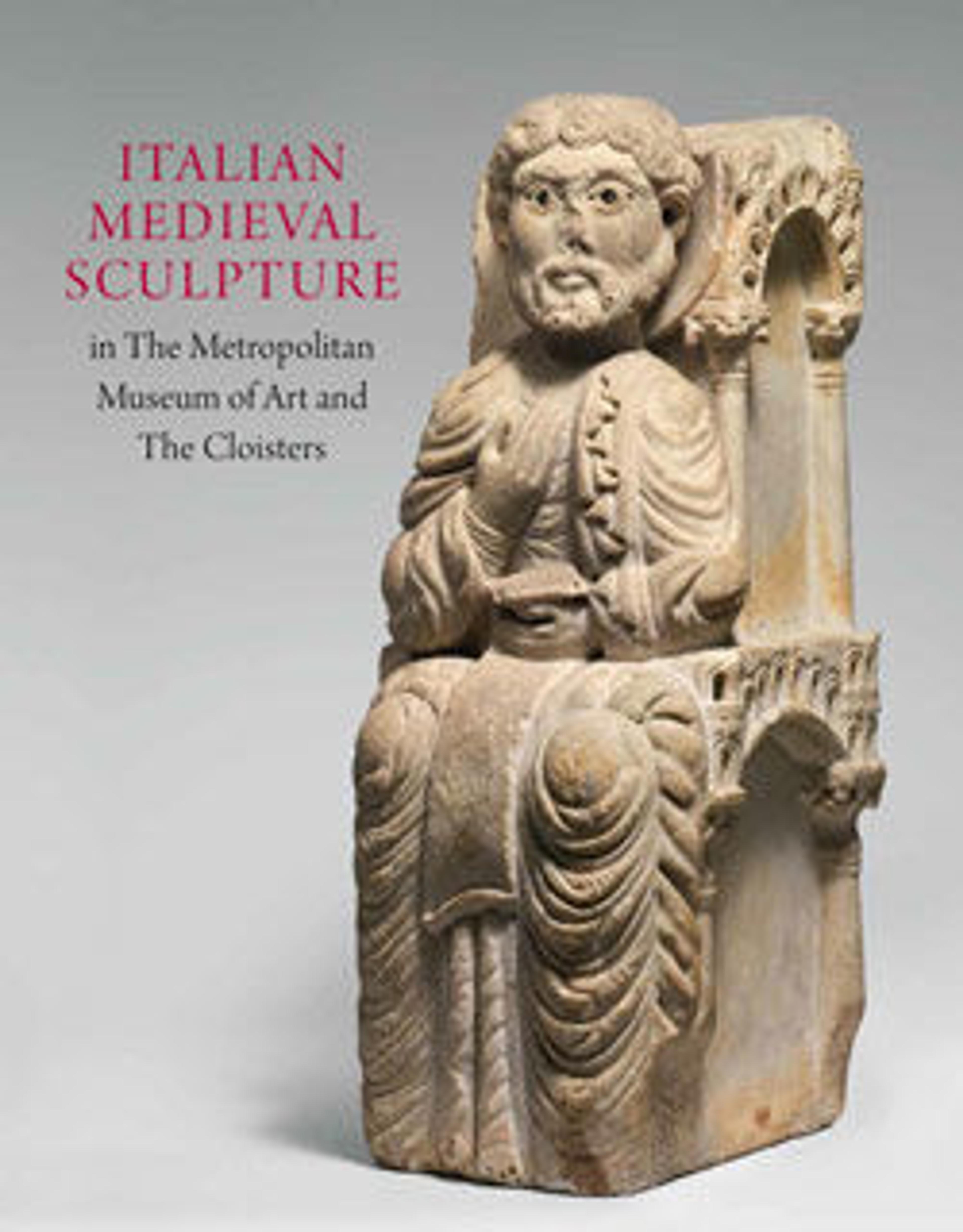

Doorway from the Church of San Nicolò, San Gemini

Artwork Details

- Title: Doorway from the Church of San Nicolò, San Gemini

- Date: carved 1000s, assembled 1100s or 1200s

- Geography: Made in San Gemini, Umbria, Central Italy

- Culture: Central Italian

- Medium: Marble (Lunense marble from Carrara)

- Dimensions: H. 11 ft. 9 in. x 8 ft. 4 in. (358.4 x 254.2 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Architectural

- Credit Line: Fletcher Fund, 1947

- Object Number: 47.100.45a–g

- Curatorial Department: Medieval Art and The Cloisters

Audio

2975. Portal from the Church of San Nicolü, San Gemini

This portal once ushered people into a small church in Umbria, the Italian region that borders Tuscany. Stand off to either side of the doorway to avoid the traffic that flows through it today.

This portal is composed of elements made at different times and in a variety of styles. Notice, for example, the two jambs, or sides of the door, with their entirely different designs. On the left jamb, curving vegetal designs wind their way around unusual motifs—find the enigmatic figure near the center right edge who stirs a pot with one hand while blowing a horn with the other. And further above him, the angel who hovers beneath an oversized flower. The right jamb pairs a lozenge pattern on the left with a vine of acanthus leaves on the right.

The style of European art prevalent in the eleventh and twelfth centuries is generally known as Romanesque. One of the hallmarks of the style can be seen in the wide rounded arch, or Roman arch, at the top of the portal. Look up at the arch to find a block just right of center that bears the Roman letters V, R, and C.

Press the green PLAY button to hear Curator Charles Little explain this curious detail.

Listen to more about this artwork

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.