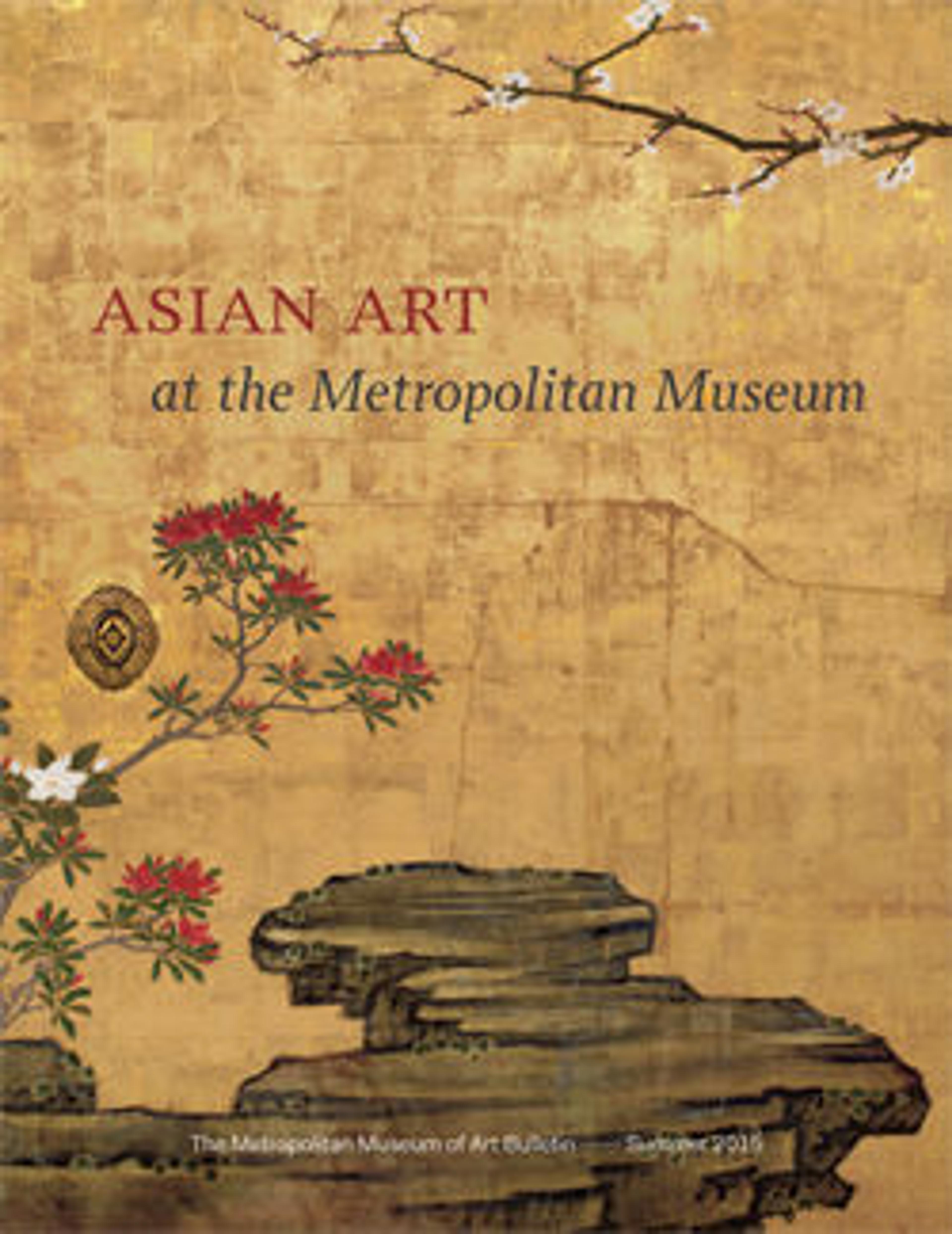

Willows and Bridge

Paintings that combine willows with a bridge and waterwheel immediately evoke the bridge over the Uji River in southeast Kyoto, a view long celebrated in literary works such as The Tale of Genji. Paintings of the Uji Bridge decorated palaces by the 900s and remained popular for the next thousand years. With their contrast of large, dramatic forms and brilliant metallic shimmer, these screens represent the zenith of the decorative style of the late sixteenth century. Above the golden bridge’s strong diagonal is a copper moon, attached to the screen by small pegs. A large waterwheel turns in the stream and stone-filled baskets protect the embankments. Gently lapping waves of silver pigment have oxidized over time to a dark gray.

Artwork Details

- 柳橋水車図屏風

- Title: Willows and Bridge

- Period: Momoyama period (1573–1615)

- Date: early 17th century

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, copper, gold, and gold leaf on paper

- Dimensions: Image (each): 61 5/16 in. × 11 ft. 5/16 in. (155.8 × 336 cm)

Overall (each): 67 5/8 in. × 11 ft. 6 9/16 in. (171.8 × 352 cm) - Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015

- Object Number: 2015.300.105.1, .2

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.