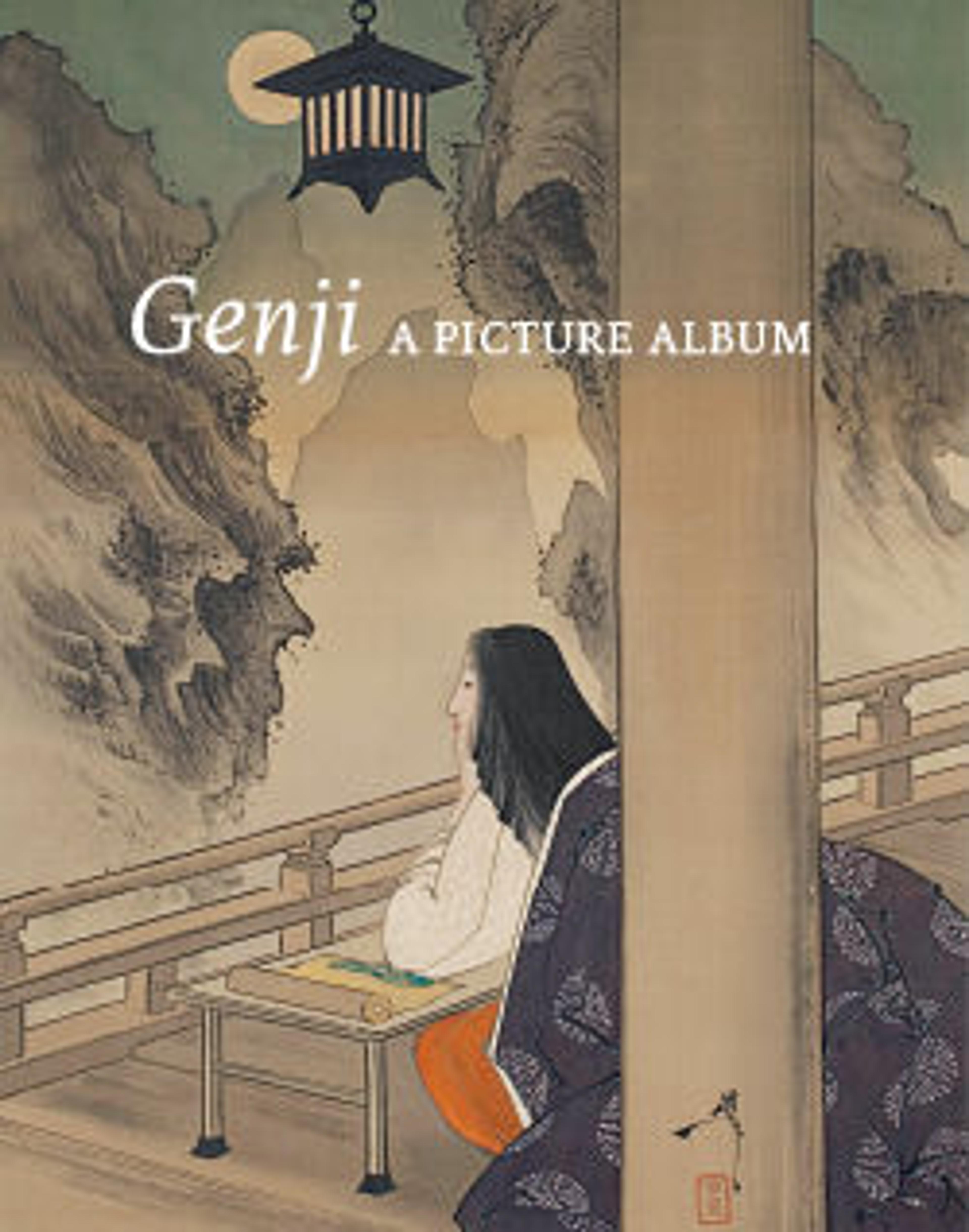

“Butterflies”

This single screen, one of the finest examples of painting by Tosa Mitsuyoshi, encapsulates the imagined visual splendor of Genji’s Rokujō estate and conflates episodes from two different days in one composition. Ladies-in-waiting from the autumn quadrant of the Umetsubo Empress (Akikonomu) have arrived in Murasaki’s spring garden on a water bird boat on the upper left. The foreground scene takes place the next day, when page girls spectacularly costumed as paradisal kalavinka birds and butterflies of the court bugaku dance arrive at the autumn quadrant via dragon boat. The girls have been sent by Murasaki with flower offerings for the Empress’s sutra reading. The profusion of cherry blossoms throughout the screen illustrates the dominance of the spring season.

Artwork Details

- 源氏物語図屏風 (胡蝶)

- Title: “Butterflies”

- Artist: Tosa Mitsuyoshi (Japanese, 1539–1613)

- Period: Momoyama period (1573–1615)

- Date: late 16th–early 17th century

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, gold, and gold leaf on paper

- Dimensions: 65 in. × 12 ft. 3/4 in. (165.1 × 367.7 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015

- Object Number: 2015.300.32

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.