Plate

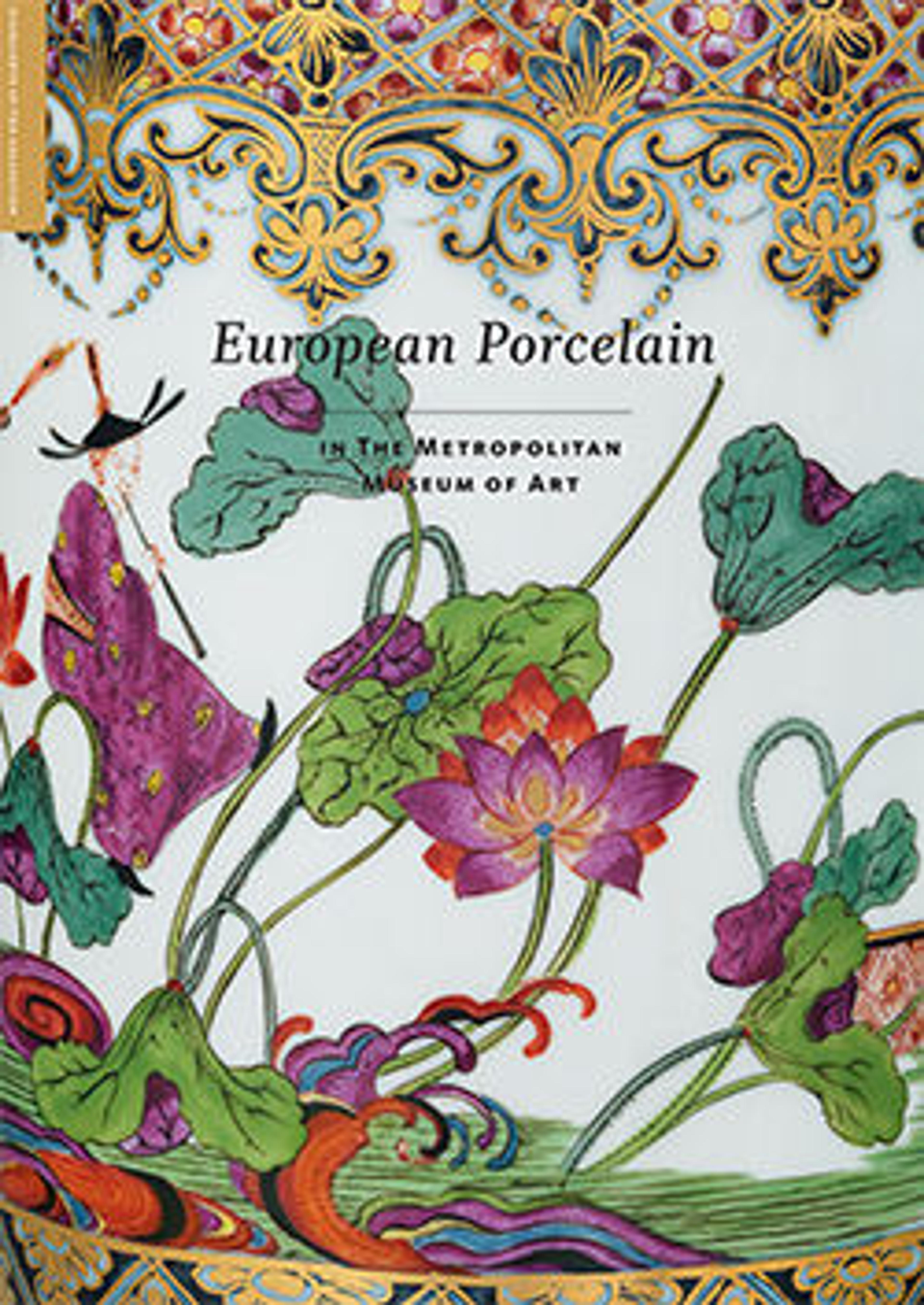

The importance of Chinese porcelain, both for the founding of the Bow factory and for its considerable commercial success in the following decades, is embodied by this Bow plate that dates from around 1755. The plate is painted with a scene of two Chinese women in robes standing in an abbreviated landscape that includes a deer, part of a fence, and rockwork from which a pine tree emerges, and the border is decorated with sprays of peonies. The palette of enamel colors is dominated by a strong rose pink and includes yellow, manganese, and two shades of both green and blue. Both the composition and the distinctive palette closely copy those of a Chinese porcelain plate (fig. 55) made for export approximately twenty to thirty years earlier during the Yongzheng period (1723–35) of the Qing Dynasty (1644– 1911). The palette of colors employed for the Chinese plate is customarily identified in the West by the French term famille rose, a designation of nineteenth-century origin that reflects the prominence of the rose-pink enamel. The painter at Bow must have had access to a Chinese plate similar to the Museum’s example due to the remarkable fidelity of the composition and the enamel colors to Chinese originals.

The Bow factory had been established around 1747, and porcelain appears to have been produced as early as the following year, as indicated by a bill dated February 1748.[1] While Bow porcelain was advertised in August 1748,[2] little is known about the factory’s production prior to 1750, although a second patent was issued in November 1749 to one of the original founders, Thomas Frye (Irish, ca. 1710–1762). The patent lists Frye’s claim that he is able to produce “a certain ware which is not inferior in beauty and fineness and is rather superior in strength than the earthenware that is brought from the East Indies and is commonly known by the name of China, Japan or porcelain ware.”[3] A number of references in the early documents concerning the factory make explicit its aim to produce porcelain in the manner of the Chinese. A bill from 1749 identifies Bow porcelain as that made at “New Canton,” and a Bow inkpot now in the British Museum, London, is inscribed MADE AT NEW CANTON 1750.[4] Not only did the factory identify itself with the Chinese city most associated with porcelain production but it also constructed its first factory to resemble the East India warehouse in Canton,[5] which must have appeared as an unusually exotic edifice in Stratford, East London, in the late 1740s.

In its early years, the factory, which was the first built expressly for ceramic production in England,[6] made useful and ornamental wares in the Chinese taste to compete with the porcelain arriving in vast quantities from China by the mid-eighteenth century. Much of Bow’s early production was decorated in underglaze blue that evoked the blue-and-white porcelains for which China was best known, and the scenes and motifs chosen for these wares reflect the chinoiserie vocabulary of the day. Bow also made white wares decorated with applied prunus branches in imitation of the so-called blanc de chine produced at Dehua in Fujian province, which represented another highly popular category of imported Chinese porcelains. For the porcelain it produced for decoration in polychrome enamels, Bow looked to imported Chinese famille rose wares for its primary inspiration. The Chinese first developed the deep- rose pink enamel in the early 1720s, and a palette revolving around this color dominated export wares for the next several decades.[7] It is likely that Bow chose famille rose wares to imitate since the other English porcelain factories at this time were more influenced by either Chinese famille verte wares, as at Worcester, or by Japanese Kakiemon-style wares, which inspired the painters at Chelsea in the 1750s.[8] Famille rose–style decoration remained popular at Bow until the early 1760s, at which time flower painting in a European manner became ascendant.

The Bow factory’s focus on Asian-inspired decoration found a receptive market among Britain’s middle and upper classes, in contrast to the Chelsea factory, which aimed its products primarily to the upper strata of society. The factory incorporated calcinated bone ash in its soft- paste porcelain body, which made its products whiter and allowed them to withstand the heat of the firing more reliably, and this more durable porcelain paste contributed to the factory’s success as well. While Bow produced figures in considerable quantities, the various tablewares that it made ensured the factory’s prosperity during the 1750s and the early 1760s. By about 1760 Bow employed around three hundred workers,9 making it the largest porcelain factory in England at the time. Not long after, the taste for Asian- inspired decoration faded, and the factory began to encounter financial difficulties that ultimately led to its demise in the late 1770s. However, the factory’s early successes helped to firmly establish England as a major producer of porcelain in the 1750s, making the importation of Chinese porcelain no longer necessary.

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 Gabszewicz 2000, p. 13. For more information about the factory, see Spero 1995, pp. 53–56; H. Young 1999, p. 197. See also Gabszewicz 2010; this short history ascribes an earlier founding date for the factory of 1744.

2 Gabszewicz 2000, p. 13.

3 Quoted in ibid., p. 15.

4 British Museum, London (1887, 0307, 1.61). A similar inkpot with the same inscription and the date of 1751 is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2864- 1901). 5 Spero 1995, p. 53.

6 Ibid.

7 For more information about the use of opaque enamels, including pink, see Sargent 2012, pp. 237–38.

8 Kakiemon- inspired decoration was also popular at Bow; see, for example, Gallagher 2015, p. 194, no. 124.

9 This information appears in an inscription written in about 1790 by Thomas Craft (British?, dates unknown), a decorator at Bow, inside the lid of box containing a bowl he decorated that is now in the British Museum (1.62). See Gabszewicz 2000, p. 16.

The Bow factory had been established around 1747, and porcelain appears to have been produced as early as the following year, as indicated by a bill dated February 1748.[1] While Bow porcelain was advertised in August 1748,[2] little is known about the factory’s production prior to 1750, although a second patent was issued in November 1749 to one of the original founders, Thomas Frye (Irish, ca. 1710–1762). The patent lists Frye’s claim that he is able to produce “a certain ware which is not inferior in beauty and fineness and is rather superior in strength than the earthenware that is brought from the East Indies and is commonly known by the name of China, Japan or porcelain ware.”[3] A number of references in the early documents concerning the factory make explicit its aim to produce porcelain in the manner of the Chinese. A bill from 1749 identifies Bow porcelain as that made at “New Canton,” and a Bow inkpot now in the British Museum, London, is inscribed MADE AT NEW CANTON 1750.[4] Not only did the factory identify itself with the Chinese city most associated with porcelain production but it also constructed its first factory to resemble the East India warehouse in Canton,[5] which must have appeared as an unusually exotic edifice in Stratford, East London, in the late 1740s.

In its early years, the factory, which was the first built expressly for ceramic production in England,[6] made useful and ornamental wares in the Chinese taste to compete with the porcelain arriving in vast quantities from China by the mid-eighteenth century. Much of Bow’s early production was decorated in underglaze blue that evoked the blue-and-white porcelains for which China was best known, and the scenes and motifs chosen for these wares reflect the chinoiserie vocabulary of the day. Bow also made white wares decorated with applied prunus branches in imitation of the so-called blanc de chine produced at Dehua in Fujian province, which represented another highly popular category of imported Chinese porcelains. For the porcelain it produced for decoration in polychrome enamels, Bow looked to imported Chinese famille rose wares for its primary inspiration. The Chinese first developed the deep- rose pink enamel in the early 1720s, and a palette revolving around this color dominated export wares for the next several decades.[7] It is likely that Bow chose famille rose wares to imitate since the other English porcelain factories at this time were more influenced by either Chinese famille verte wares, as at Worcester, or by Japanese Kakiemon-style wares, which inspired the painters at Chelsea in the 1750s.[8] Famille rose–style decoration remained popular at Bow until the early 1760s, at which time flower painting in a European manner became ascendant.

The Bow factory’s focus on Asian-inspired decoration found a receptive market among Britain’s middle and upper classes, in contrast to the Chelsea factory, which aimed its products primarily to the upper strata of society. The factory incorporated calcinated bone ash in its soft- paste porcelain body, which made its products whiter and allowed them to withstand the heat of the firing more reliably, and this more durable porcelain paste contributed to the factory’s success as well. While Bow produced figures in considerable quantities, the various tablewares that it made ensured the factory’s prosperity during the 1750s and the early 1760s. By about 1760 Bow employed around three hundred workers,9 making it the largest porcelain factory in England at the time. Not long after, the taste for Asian- inspired decoration faded, and the factory began to encounter financial difficulties that ultimately led to its demise in the late 1770s. However, the factory’s early successes helped to firmly establish England as a major producer of porcelain in the 1750s, making the importation of Chinese porcelain no longer necessary.

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Munger, European Porcelain in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018)

1 Gabszewicz 2000, p. 13. For more information about the factory, see Spero 1995, pp. 53–56; H. Young 1999, p. 197. See also Gabszewicz 2010; this short history ascribes an earlier founding date for the factory of 1744.

2 Gabszewicz 2000, p. 13.

3 Quoted in ibid., p. 15.

4 British Museum, London (1887, 0307, 1.61). A similar inkpot with the same inscription and the date of 1751 is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2864- 1901). 5 Spero 1995, p. 53.

6 Ibid.

7 For more information about the use of opaque enamels, including pink, see Sargent 2012, pp. 237–38.

8 Kakiemon- inspired decoration was also popular at Bow; see, for example, Gallagher 2015, p. 194, no. 124.

9 This information appears in an inscription written in about 1790 by Thomas Craft (British?, dates unknown), a decorator at Bow, inside the lid of box containing a bowl he decorated that is now in the British Museum (1.62). See Gabszewicz 2000, p. 16.

Artwork Details

- Title: Plate

- Manufactory: Bow Porcelain Factory (British, 1747–1776)

- Date: ca. 1755

- Culture: British, Bow, London

- Medium: Soft-paste porcelain decorated in polychrome enamels

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 1 × 9 × 9 in. (2.5 × 22.9 × 22.9 cm)

- Classification: Ceramics-Porcelain

- Credit Line: Purchase, Gift of Mrs. George Whitney, Mrs. William C. Breed and funds from various donors, by exchange, 2014

- Object Number: 2014.600

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.