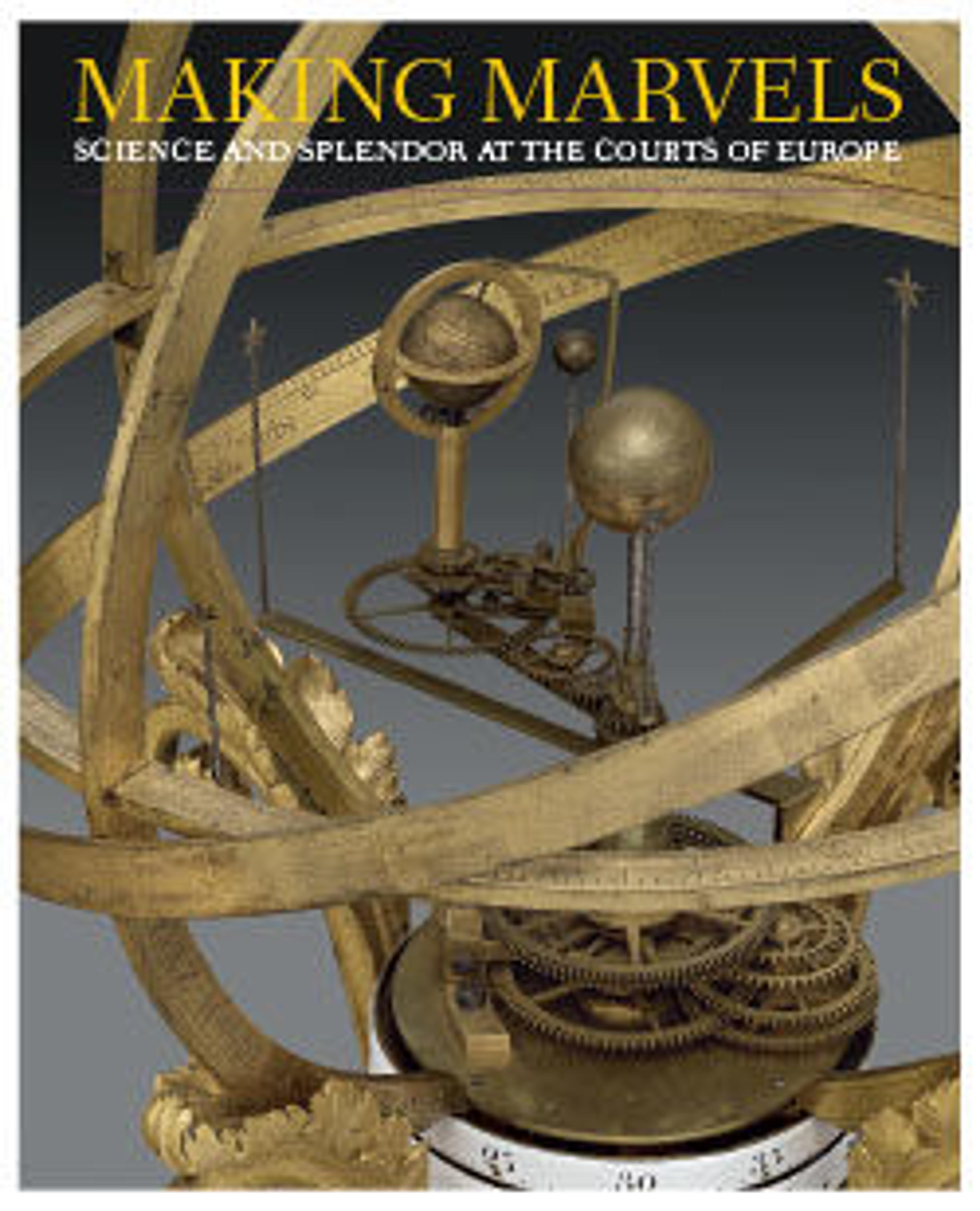

Automaton clock in the form of Urania, Muse of Astronomy

In 1471 the German astronomer Johann Müller (1436–1476), better known by his latinized name, Regiomontanus,[1] left Vienna, where he had been a pupil of and later an assistant to the astronomer Georg Peuerbach (1423–1461).[2] Regiomontanus settled in Nürnberg, and soon became the central figure in a circle of amateurs and aristocrats who were interested in cosmology and astronomy. One member of the circle, Bernard Walther (ca. 1430–1504), set up an astronomical observatory in his house, as well as the press that published Peuerbach’s highly influential treatise Theoricae Novae Planetarum (New Theory of Planets) about 1474.[3] Regiomontanus is credited with the construction of the astronomical instruments that he and Walther used in the observatory,[4] and he probably provided the calculations for an ambitious astronomical clock that registered not only the time but also the positions of the sun, moon, and planets. The clock no longer exists, but it was mentioned in a broadsheet Regiomontanus printed in 1475, and it is likely that it was the same clock sold in 1529 to the Archbishop of Mainz, Cardinal Albrecht IV of Brandenburg (died 1545).[5]

Sixteenth-century Nürnberg craftsmen inherited these skills, and their grounding in astronomy and mathematics combined with the tradition of working in brass that flourished in the city produced some of the most celebrated mathematical instruments and domestic or small clocks (Kleinuhren) of the century. These included, for example, the classic astrolabes of Georg Hartmann (1489–1564)[6] and the ingeniously nesting clockwork-driven globes of Christian Heiden (1526–1576).[7] Clocks with movements by Hans Gruber (died 1597) of Nürnberg are often housed in cases made of cast, chased, and gilded brass; one such clock includes plaquettes depicting scenes from the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son by the sculptor Leonhard Danner (1507–1587),[8] and another, initialed “MZ,” has been identified as the design of the Nürnberg goldsmith Matthias Zündt (ca. 1498–1572).[9]

In spite of the fame of their timepieces, however, sixteenth-century records of Nürnberg craftsmen reveal remarkably few identified as clockmakers, even if some of them are known to have joined other companies of craftsmen.[10] Their relatively few numbers probably account for the rarity of surviving Nürnberg clocks.

Conditions in the early seventeenth century were not materially different. By then, the clockmakers of Nürnberg’s chief rival, Augsburg, were making mechanized miniature figures of human beings, birds, animals both real and fantastic,[11] and ships that moved along a tabletop, spitting fire from tiny cannons[12] while marking the hours. At first, the figures for these clocks were made of gilded repoussé copper and were supported on circular or oval bases of richly embossed metal housing the springs that drove the motions of the figures as well as the hands of the clocks they incorporated. About the end of the sixteenth century metal bases began to be superseded by wooden bases made of ebony, ebony veneer, and sometimes fruitwood darkened to look like ebony.[13]

With the coming of the wooden base, cast figures of gilded brass, such as the lion,[14] which must have been a popular model, or the rarely encountered Imperial Eagle,[15] among many other small statuettes, quickly replaced figures largely made of embossed and gilded copper. Nürnberg’s tradition of casting figures in bronze was comparable to Augsburg’s, and the technology for casting in brass was well understood in both cities. Thus the makers of Urania, the Muse of Astronomy, were easily able to produce a line of serially cast brass automaton figures. At least seven of these still exist; four of them are illustrated by Klaus Maurice.[16] All were activated by movements provided by the Nürnberg clockmaker Paullus Schiller. Born in Nürnberg on October 11, 1583, Schiller is now known primarily for the Urania automata. He married on May 11, 1614, became a master clockmaker in 1617, and died in Nürnberg on April 13, 1634.[17]

On the clock, Urania reclines on a grassy hillock; each hour she turns her head to watch the revolving sphere mounted beside her while lifting her arm to move her pointer to the correct hour displayed on a chapter of hours (I–XII) mounted on the circumference of the sphere. Not only is she an appropriate representative of the city of the astronomical observatory, but also, as Maurice has observed,[18] her reclining form alludes to a figure atop a writing chest, the product of another proud tradition in Nürnberg, that of the goldsmith, and in particular one of Nürnberg’s best: Wenzel Jamnitzer (1508–1585).[19]

The miniature muse of the clock is supported above a gallery of foliate scrolls and animal masks in an openwork pattern designed to allow the sound of the bell mounted inside it to be heard. The gallery, in turn, rests on a rectangular platform of ebony with ebony ripple moldings on all four sides, and it supports a decorative frieze of brass trefoils that bears traces of silvering. Attached to the bottom of the structure is the rectangular brass plate that serves as the top plate of the movement of the clock. The entire assembly is hinged to the rest of the wooden base so that the movement can be lifted and its springs wound from the underside without upending the entire clock. The remaining portion of the base consists of a concave molding above a second band of ripple molding and a base with a shallow drawer that opens on the proper left side of the base. One of the small brass studs that dot the wooden base serves as a knob for the drawer that was intended to hold both a key for the case and one for winding the movement. The center of the front portion is now ornamented by an openwork escutcheon of the keyhole for the lock of the case. The entire clock is now supported on four feet that are replacements for an earlier type of foot. To judge from circular holes that remain in the wood on the underside, these were originally the bun-shaped variety still found on the Metropolitan Museum’s Eagle Automaton.[20]

The movement contained within the wooden base consists of two rectangular, gilded-brass plates held apart by six cylindrical pillars riveted to the top plate and pinned to the back plate. The striking train (on the proper right side) consists of a going barrel, three brass wheels, and a fly. It strikes the hours (1–12) on a bell mounted on the outside of the top plate, and it is governed by a large, floridly ornamented indexing arm and a steel count wheel with interior cut teeth. The count wheel is held in place by an ornamented openwork cock that is screwed to the exterior side of the back plate (see illustration above). A shaft transmits motion from the train through the back of the figure of the muse to her head and right arm.

The going train (on the proper left side of the movement) has an engraved brass going barrel and three brass wheels ending in a verge escapement. A balance with a spiral hair spring and a new cock has been added, probably not long after the invention of the balance spring in late 1674 by the Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695).[21] The Arabic numbers 1, 2, 3 engraved directly on the back plate are now without purpose; they are all that remain of the hog’s bristle regulation for the original balance. As in the striking train, a shaft transmits motion to the revolving sphere on which the hours (I–XII) are inscribed. In addition to the count-wheel assembly and the balance, the back plate carries two toothed wheels, one with the winding square for the going train in its center, whose purpose is to prevent overwinding the mainspring. The signature of the clockmaker “Paullus Schiller” is accompanied by impressive foliate flourishes.

There is no fusee in either the striking train or in the going train, where it might be more reasonably expected. In this particular as in others, this clock is quite unlike the large majority of automata made in Augsburg where the spring and fusee device was employed. The timekeeping properties of this clock originally must have been fairly poor. The dial of the clock, in fact, registers hours and half hours only, but the application of the balance spring would have made a significant difference in the accuracy of the clock. In fact, for a few years after Huygens’s invention, several well-known clockmakers, including Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) in London[22] and Nicolas Gribelin (1637–1719) in Paris,[23] made watches without fusees that relied on their balance springs alone for accurate timekeeping. These experiments were, however, soon abandoned.

As might be expected of a clock that was active for a long period, there are repairs to both the movement and the case. A keyhole-shaped steel coqueret now attached to the table of the balance cock, and one or two wheels replaced in the going train attest to a long history of use. The ornament that now serves as an escutcheon for the keyhole in the middle of the front of the case has been removed from the concave molding on one side of the case, and it has been modified in an attempt to fit the keyhole. The keyhole is now unusable. Traces of the mounting of a similarly shaped ornament on the opposite side of the case and a third that was originally on the front are visible. Other replacements include the four baroque feet, some of the brass knobs attached to various parts of the wooden base, and a few areas of ripple molding that are made of stained fruitwood instead of ebony. The two ends of the trefoil frieze on the back of the clock are missing, as is one of the trefoils on the remaining frieze. The gilding of the figure is worn and lightly abraded, but not in a way that is inconsistent with normal use. The clock is in running condition.

A part of the distinguished New York collection of Peter D. Guggenheim for more than forty-five years, the clock was purchased at auction by the Museum with funds provided by the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Acquisitions Fund.[24]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] For more about Regiomontanus, see Zinner 1968.

[2] Hellman and Swerdlow 1978.

[3] Ibid., p. 474.

[4] Zinner 1956, pp. 482–83; Pannekoek 1961, pp. 181–82.

[5] A drawing of the clock is preserved in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. See Maurice 1975; Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 56–58, vol. 2, p. 36, no. 211, and fig. 211; Leopold 2002, p. 505, n. 1.

[6] See, for example, R. Webster and M. Webster 1998, pp. 53–57.

[7] Leopold 1986, pp. 72–86; Leopold 2002, pp. 518–19 and figs. 18, 19.

[8] Formerly in the collection of Ruth and Leopold Blumka in New York. See Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 70, no. 530, and fig. 530.

[9] Ibid., pp. 24–25, no. 112, and fig. 112.

[10] Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 142–43. An addendum (pp. 299–300) lists the records of clockmakers found in the Staatsarchiv Nurnberg, among them only six who specialized in domestic clocks in the sixteenth century. Only a few more were recorded in the seventeenth century.

[11] See 29.52.14 in this volume for two examples in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection.

[12] See de Conihout et al. 2001.

[13] For a further discussion of ebony bases as they were made in Augsburg, see Himmelheber 1980.

[14] For the Metropolitan Museum’s example (acc. no. 29.52.15), see p. 56, fig. 22, in this volume. Many others exist.

[15] See 29.52.14 in this volume for the Metropolitan Museum’s example.

[16] Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 55, nos. 378–81, and figs. 378–81; no. 380 is the Urania automaton clock now in the Metropolitan Museum. An additional example was included as no. 354 in a sale held at Auktionen Dr. Crott in Mannheim, Germany, on Nov. 13, 2004. Another was formerly in the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Berge; see Christie’s 2009, vol. 5, no. 721. See also Artcurial 2012, pp. 30–35, no. 34, ill., for another example in a recent sale.

[17] See Grieb 2007, vol. 3, p. 1329, in which he is identified as a Kleinuhrmacher. See also Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 141, 300.

[18] Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 55, no. 374, and fig. 374.

[19] The chest, known to have been the property of the Saxon Electress Sophia in 1623, is now in the collection of the Grunes Gewolbe in Dresden (inv. no. V 599). See Sponsel 1925, p. 48; see also Martin Angerer in Wenzel Jamnitzer 1985, pp. 225–26, no. 20 (with bibliography).

[20] See 29.52.14 this volume.

[21] See 17.190.1417 in this volume.

[22] See 17.190.1512 in this volume.

[23] Acc. no. 17.190.1559 is an example in the Museum’s collection. See Sun King 1984, p. 223, no. 76.

[24] Christie’s 2015, no. 30, ill.

Sixteenth-century Nürnberg craftsmen inherited these skills, and their grounding in astronomy and mathematics combined with the tradition of working in brass that flourished in the city produced some of the most celebrated mathematical instruments and domestic or small clocks (Kleinuhren) of the century. These included, for example, the classic astrolabes of Georg Hartmann (1489–1564)[6] and the ingeniously nesting clockwork-driven globes of Christian Heiden (1526–1576).[7] Clocks with movements by Hans Gruber (died 1597) of Nürnberg are often housed in cases made of cast, chased, and gilded brass; one such clock includes plaquettes depicting scenes from the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son by the sculptor Leonhard Danner (1507–1587),[8] and another, initialed “MZ,” has been identified as the design of the Nürnberg goldsmith Matthias Zündt (ca. 1498–1572).[9]

In spite of the fame of their timepieces, however, sixteenth-century records of Nürnberg craftsmen reveal remarkably few identified as clockmakers, even if some of them are known to have joined other companies of craftsmen.[10] Their relatively few numbers probably account for the rarity of surviving Nürnberg clocks.

Conditions in the early seventeenth century were not materially different. By then, the clockmakers of Nürnberg’s chief rival, Augsburg, were making mechanized miniature figures of human beings, birds, animals both real and fantastic,[11] and ships that moved along a tabletop, spitting fire from tiny cannons[12] while marking the hours. At first, the figures for these clocks were made of gilded repoussé copper and were supported on circular or oval bases of richly embossed metal housing the springs that drove the motions of the figures as well as the hands of the clocks they incorporated. About the end of the sixteenth century metal bases began to be superseded by wooden bases made of ebony, ebony veneer, and sometimes fruitwood darkened to look like ebony.[13]

With the coming of the wooden base, cast figures of gilded brass, such as the lion,[14] which must have been a popular model, or the rarely encountered Imperial Eagle,[15] among many other small statuettes, quickly replaced figures largely made of embossed and gilded copper. Nürnberg’s tradition of casting figures in bronze was comparable to Augsburg’s, and the technology for casting in brass was well understood in both cities. Thus the makers of Urania, the Muse of Astronomy, were easily able to produce a line of serially cast brass automaton figures. At least seven of these still exist; four of them are illustrated by Klaus Maurice.[16] All were activated by movements provided by the Nürnberg clockmaker Paullus Schiller. Born in Nürnberg on October 11, 1583, Schiller is now known primarily for the Urania automata. He married on May 11, 1614, became a master clockmaker in 1617, and died in Nürnberg on April 13, 1634.[17]

On the clock, Urania reclines on a grassy hillock; each hour she turns her head to watch the revolving sphere mounted beside her while lifting her arm to move her pointer to the correct hour displayed on a chapter of hours (I–XII) mounted on the circumference of the sphere. Not only is she an appropriate representative of the city of the astronomical observatory, but also, as Maurice has observed,[18] her reclining form alludes to a figure atop a writing chest, the product of another proud tradition in Nürnberg, that of the goldsmith, and in particular one of Nürnberg’s best: Wenzel Jamnitzer (1508–1585).[19]

The miniature muse of the clock is supported above a gallery of foliate scrolls and animal masks in an openwork pattern designed to allow the sound of the bell mounted inside it to be heard. The gallery, in turn, rests on a rectangular platform of ebony with ebony ripple moldings on all four sides, and it supports a decorative frieze of brass trefoils that bears traces of silvering. Attached to the bottom of the structure is the rectangular brass plate that serves as the top plate of the movement of the clock. The entire assembly is hinged to the rest of the wooden base so that the movement can be lifted and its springs wound from the underside without upending the entire clock. The remaining portion of the base consists of a concave molding above a second band of ripple molding and a base with a shallow drawer that opens on the proper left side of the base. One of the small brass studs that dot the wooden base serves as a knob for the drawer that was intended to hold both a key for the case and one for winding the movement. The center of the front portion is now ornamented by an openwork escutcheon of the keyhole for the lock of the case. The entire clock is now supported on four feet that are replacements for an earlier type of foot. To judge from circular holes that remain in the wood on the underside, these were originally the bun-shaped variety still found on the Metropolitan Museum’s Eagle Automaton.[20]

The movement contained within the wooden base consists of two rectangular, gilded-brass plates held apart by six cylindrical pillars riveted to the top plate and pinned to the back plate. The striking train (on the proper right side) consists of a going barrel, three brass wheels, and a fly. It strikes the hours (1–12) on a bell mounted on the outside of the top plate, and it is governed by a large, floridly ornamented indexing arm and a steel count wheel with interior cut teeth. The count wheel is held in place by an ornamented openwork cock that is screwed to the exterior side of the back plate (see illustration above). A shaft transmits motion from the train through the back of the figure of the muse to her head and right arm.

The going train (on the proper left side of the movement) has an engraved brass going barrel and three brass wheels ending in a verge escapement. A balance with a spiral hair spring and a new cock has been added, probably not long after the invention of the balance spring in late 1674 by the Dutch mathematician Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695).[21] The Arabic numbers 1, 2, 3 engraved directly on the back plate are now without purpose; they are all that remain of the hog’s bristle regulation for the original balance. As in the striking train, a shaft transmits motion to the revolving sphere on which the hours (I–XII) are inscribed. In addition to the count-wheel assembly and the balance, the back plate carries two toothed wheels, one with the winding square for the going train in its center, whose purpose is to prevent overwinding the mainspring. The signature of the clockmaker “Paullus Schiller” is accompanied by impressive foliate flourishes.

There is no fusee in either the striking train or in the going train, where it might be more reasonably expected. In this particular as in others, this clock is quite unlike the large majority of automata made in Augsburg where the spring and fusee device was employed. The timekeeping properties of this clock originally must have been fairly poor. The dial of the clock, in fact, registers hours and half hours only, but the application of the balance spring would have made a significant difference in the accuracy of the clock. In fact, for a few years after Huygens’s invention, several well-known clockmakers, including Thomas Tompion (1639–1713) in London[22] and Nicolas Gribelin (1637–1719) in Paris,[23] made watches without fusees that relied on their balance springs alone for accurate timekeeping. These experiments were, however, soon abandoned.

As might be expected of a clock that was active for a long period, there are repairs to both the movement and the case. A keyhole-shaped steel coqueret now attached to the table of the balance cock, and one or two wheels replaced in the going train attest to a long history of use. The ornament that now serves as an escutcheon for the keyhole in the middle of the front of the case has been removed from the concave molding on one side of the case, and it has been modified in an attempt to fit the keyhole. The keyhole is now unusable. Traces of the mounting of a similarly shaped ornament on the opposite side of the case and a third that was originally on the front are visible. Other replacements include the four baroque feet, some of the brass knobs attached to various parts of the wooden base, and a few areas of ripple molding that are made of stained fruitwood instead of ebony. The two ends of the trefoil frieze on the back of the clock are missing, as is one of the trefoils on the remaining frieze. The gilding of the figure is worn and lightly abraded, but not in a way that is inconsistent with normal use. The clock is in running condition.

A part of the distinguished New York collection of Peter D. Guggenheim for more than forty-five years, the clock was purchased at auction by the Museum with funds provided by the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Acquisitions Fund.[24]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] For more about Regiomontanus, see Zinner 1968.

[2] Hellman and Swerdlow 1978.

[3] Ibid., p. 474.

[4] Zinner 1956, pp. 482–83; Pannekoek 1961, pp. 181–82.

[5] A drawing of the clock is preserved in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. See Maurice 1975; Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 56–58, vol. 2, p. 36, no. 211, and fig. 211; Leopold 2002, p. 505, n. 1.

[6] See, for example, R. Webster and M. Webster 1998, pp. 53–57.

[7] Leopold 1986, pp. 72–86; Leopold 2002, pp. 518–19 and figs. 18, 19.

[8] Formerly in the collection of Ruth and Leopold Blumka in New York. See Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 70, no. 530, and fig. 530.

[9] Ibid., pp. 24–25, no. 112, and fig. 112.

[10] Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 142–43. An addendum (pp. 299–300) lists the records of clockmakers found in the Staatsarchiv Nurnberg, among them only six who specialized in domestic clocks in the sixteenth century. Only a few more were recorded in the seventeenth century.

[11] See 29.52.14 in this volume for two examples in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection.

[12] See de Conihout et al. 2001.

[13] For a further discussion of ebony bases as they were made in Augsburg, see Himmelheber 1980.

[14] For the Metropolitan Museum’s example (acc. no. 29.52.15), see p. 56, fig. 22, in this volume. Many others exist.

[15] See 29.52.14 in this volume for the Metropolitan Museum’s example.

[16] Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 55, nos. 378–81, and figs. 378–81; no. 380 is the Urania automaton clock now in the Metropolitan Museum. An additional example was included as no. 354 in a sale held at Auktionen Dr. Crott in Mannheim, Germany, on Nov. 13, 2004. Another was formerly in the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Berge; see Christie’s 2009, vol. 5, no. 721. See also Artcurial 2012, pp. 30–35, no. 34, ill., for another example in a recent sale.

[17] See Grieb 2007, vol. 3, p. 1329, in which he is identified as a Kleinuhrmacher. See also Maurice 1976, vol. 1, pp. 141, 300.

[18] Maurice 1976, vol. 2, p. 55, no. 374, and fig. 374.

[19] The chest, known to have been the property of the Saxon Electress Sophia in 1623, is now in the collection of the Grunes Gewolbe in Dresden (inv. no. V 599). See Sponsel 1925, p. 48; see also Martin Angerer in Wenzel Jamnitzer 1985, pp. 225–26, no. 20 (with bibliography).

[20] See 29.52.14 this volume.

[21] See 17.190.1417 in this volume.

[22] See 17.190.1512 in this volume.

[23] Acc. no. 17.190.1559 is an example in the Museum’s collection. See Sun King 1984, p. 223, no. 76.

[24] Christie’s 2015, no. 30, ill.

Artwork Details

- Title: Automaton clock in the form of Urania, Muse of Astronomy

- Maker: Paullus Schiller (German, 1583–1634)

- Date: ca. 1620–30

- Culture: German, Nuremberg

- Medium: Case: partly gilded and partly silvered brass, copper with traces of silver, ebony, and ebony veneer; Movement: gilded brass and partly blued steel

- Dimensions: Overall (confirmed): 8 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 6 1/4 in. (21 × 24.1 × 15.9 cm)

- Classification: Horology

- Credit Line: Purchase, Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Acquisitions Fund, 2015

- Object Number: 2015.76

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.