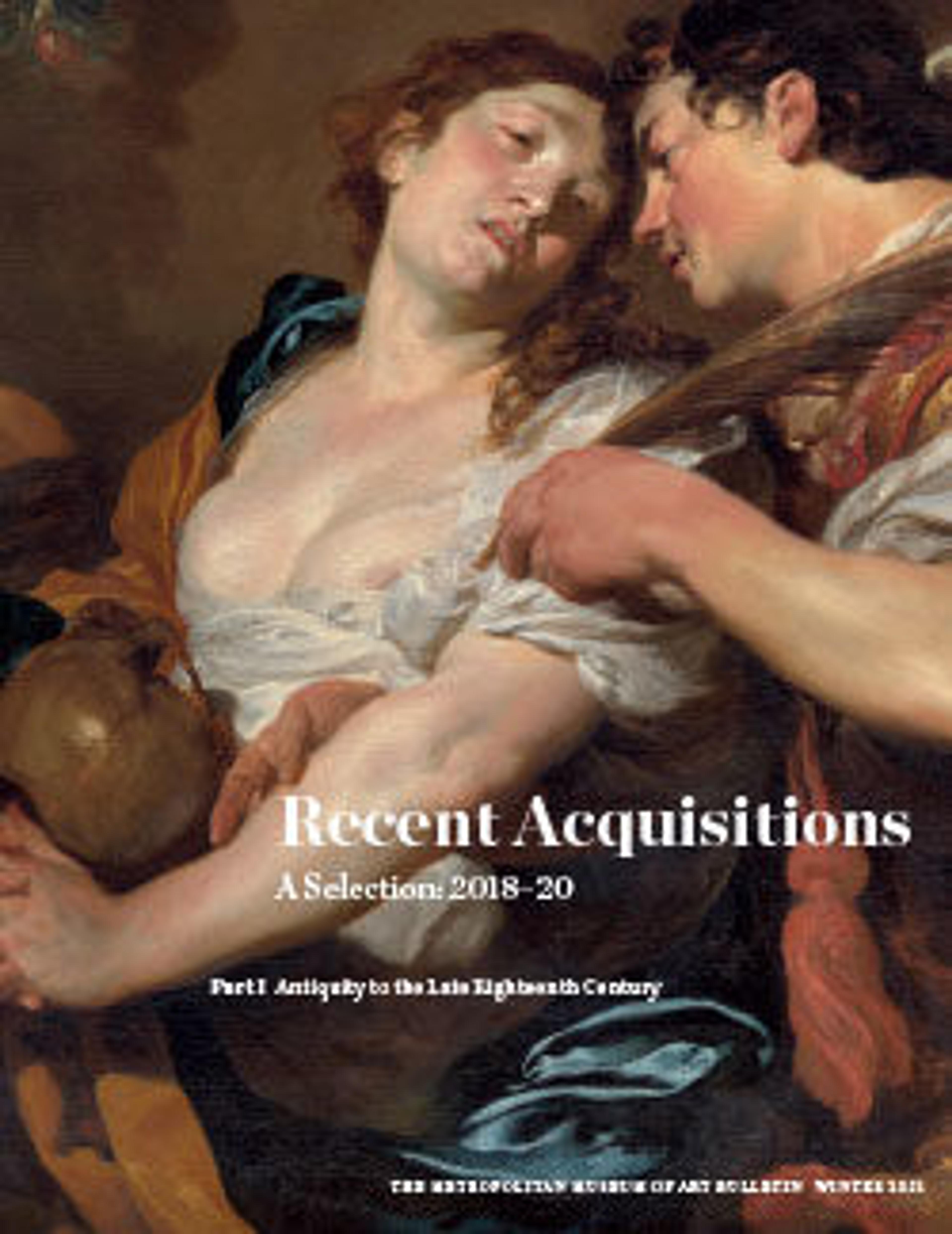

The Temptation of Saint Mary Magdalen

Born in northern Germany but active in Amsterdam, Rome, and Venice, Liss cultivated his style as he encountered different influences on his travels. He probably made this painting in Venice, and it responds to the sensuality and luscious brushwork of that city’s artistic tradition. Mary Magdalen, often invoked as a symbol of penance, is shown cradling a skull in her arms and rejecting worldly riches, offered by the figure on the left, in favor of an angel who bears the palm of victory. Her back-tilted head, half-closed eyes, and exposed breasts merge with the lush paint handling in an almost shocking eroticism.

Artwork Details

- Title: The Temptation of Saint Mary Magdalen

- Artist: Johann Liss (German, Oldenburg ca. 1595/1600–1631 Verona)

- Date: ca. 1626

- Medium: Oil on canvas

- Dimensions: 38 7/8 × 49 1/2 in. (98.8 × 125.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Walter and Leonore Annenberg Acquisitions Endowment Fund; Gifts of Irma N. Straus and Lionel F. Straus Jr., in memory of his parents, and Bequests of Milena Jurzykowski and Theodore M. Davis, by exchange; Gwynne Andrews and Victor Wilbour Memorial Funds; Charles and Jessie Price Gift, and funds from various donors, 2020

- Object Number: 2020.220

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.