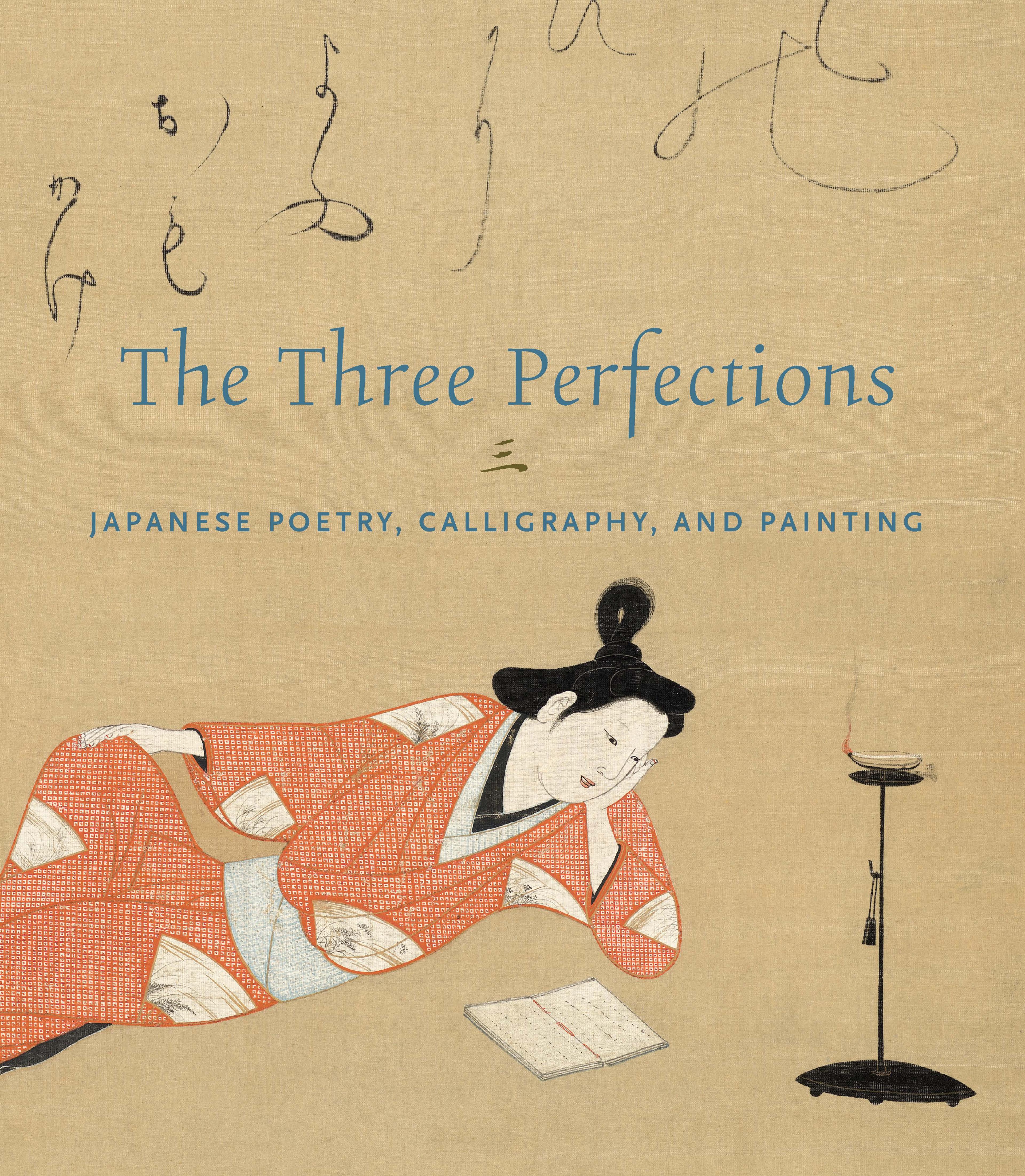

Letter

This letter in the hand of female haiku poet Shiba Sonome has been lovingly preserved in a mounting fashioned from gorgeous brocade silks of a woman’s kimono attesting to the reverence held by afficionados of her poetry through the ages.Though informally brushed, Sonome’s elegant handwriting still betrays her excellent training in calligraphy as a daughter of a Shinto priest who served at Ise Shrine, and who later became the wife of a doctor. The full content of the letter and who it was addressed to still need to be deciphered, but the random list of subjects on the right, including both place names—such as Shūgakuin Imperial Villa in Kyoto—gives the impression of being a list of poetry topics she has sent to a fellow poet.

Sonome in 1690 became a disciple of the famous haiku poet Matsuo Bashō (1694) when he was near the end of life, though the surviving correspondence between them demonstrates the deep literary and spiritual connection they shared. Sonome’s religious training in both Shinto and Zen Buddhism infused her lifestyle and poetry. In 1694, Bashō planned a final pilgrimage to Ise Shrine, and along the way he paid her a visit in Osaka, though he never made it to Ise and died in autumn of that year, just as the chrysanthemums were about to bloom. During his final meeting with Sonome, the master composed a now famous haiku to honor her reputation for living a life of unsullied spiritual purity and flawless beauty even as she was entering her third decade:

白菊の目に立てゝ見る塵もなし

Shiragiku no / me ni tatete miru / chiri mo nashi

Looking closely

at this white chrysanthemum—

not even a speck of dust.

(Trans. John T. Carpenter)

No doubt inspired by this poem, one of Sonome’s most famous published works was entitled Dust on Chrysanthemums (Kiku no Chiri, 菊の塵). After the death of her husband, she moved to Edo and became acquainted with Enomoto Kikaku (1661–1707, one of Bashō’s most influential pupils. She also worked as a doctor to help people with eye ailments. In 1718, she took the tonsure and was given the Buddhist name Chikyō-ni 智鏡尼

Sonome in 1690 became a disciple of the famous haiku poet Matsuo Bashō (1694) when he was near the end of life, though the surviving correspondence between them demonstrates the deep literary and spiritual connection they shared. Sonome’s religious training in both Shinto and Zen Buddhism infused her lifestyle and poetry. In 1694, Bashō planned a final pilgrimage to Ise Shrine, and along the way he paid her a visit in Osaka, though he never made it to Ise and died in autumn of that year, just as the chrysanthemums were about to bloom. During his final meeting with Sonome, the master composed a now famous haiku to honor her reputation for living a life of unsullied spiritual purity and flawless beauty even as she was entering her third decade:

白菊の目に立てゝ見る塵もなし

Shiragiku no / me ni tatete miru / chiri mo nashi

Looking closely

at this white chrysanthemum—

not even a speck of dust.

(Trans. John T. Carpenter)

No doubt inspired by this poem, one of Sonome’s most famous published works was entitled Dust on Chrysanthemums (Kiku no Chiri, 菊の塵). After the death of her husband, she moved to Edo and became acquainted with Enomoto Kikaku (1661–1707, one of Bashō’s most influential pupils. She also worked as a doctor to help people with eye ailments. In 1718, she took the tonsure and was given the Buddhist name Chikyō-ni 智鏡尼

Artwork Details

- 斯波園女筆 消息

- Title: Letter

- Artist: Shiba Sonome 斯波園女 (Japanese, 1664–1726)

- Period: Edo period (1615–1868)

- Date: 1696

- Culture: Japan

- Medium: Letter mounted as a hanging scroll; ink on paper

- Dimensions: Image: 7 3/16 × 20 1/8 in. (18.3 × 51.1 cm)

Overall with mounting: 36 1/2 × 21 1/8 in. (92.7 × 53.7 cm) - Classification: Calligraphy

- Credit Line: Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Gift of Mary and Cheney Cowles, 2022

- Object Number: 2022.432.14

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.