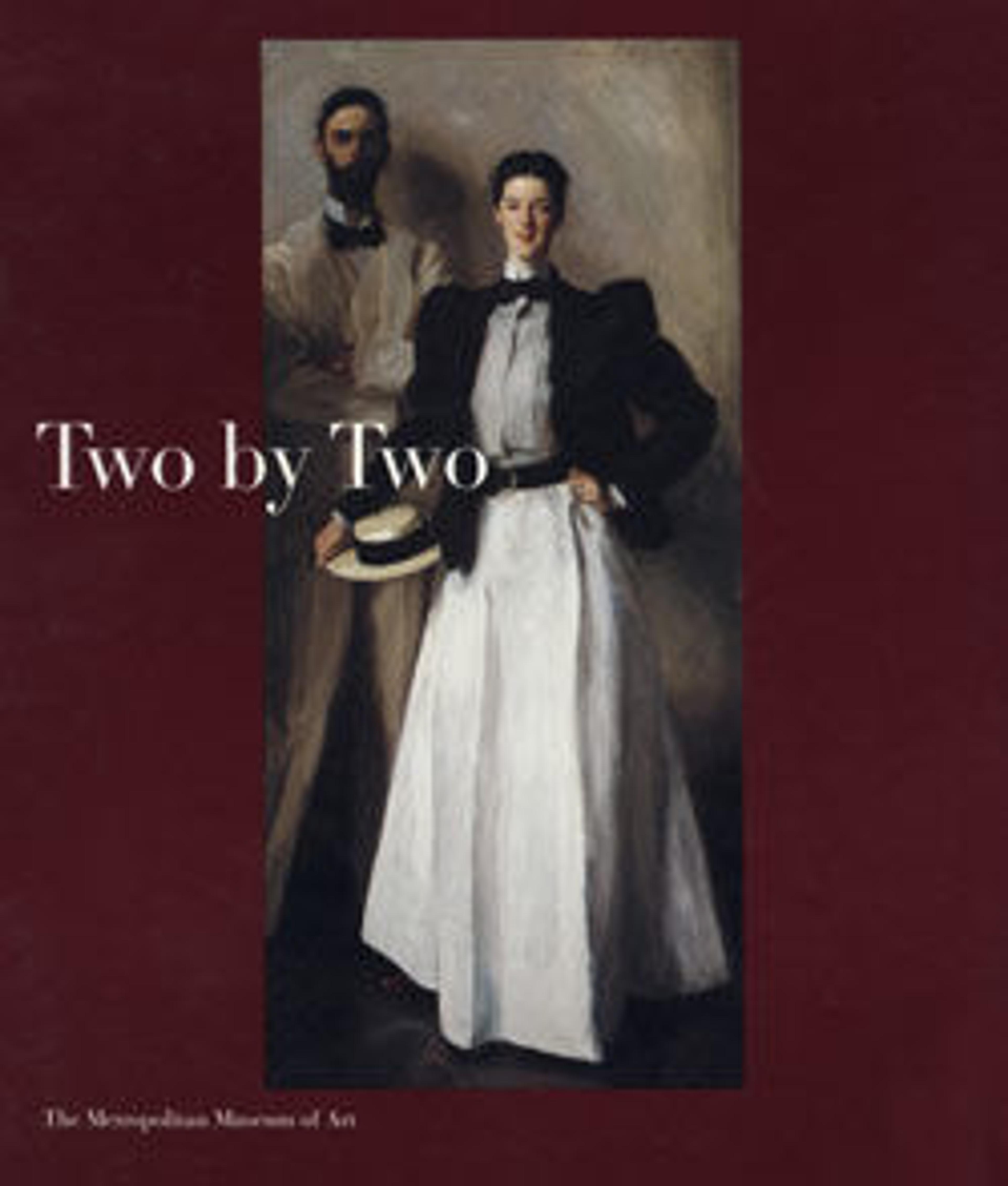

Two by Two

Two by Two presents a correlated history of women's and men's apparel from the eighteenth century to the 1970s. We do not seek to prove a direct parallel between the evolution of the two, yet we do observe points of profound similarity. We do not seek to elide clothing's practice of gender differentiation, but we can see some transgender crossings. We do not offer a theory of dress on this Noah's Ark of fashion history, but we note that our assembly of the sexes is vividly more true to life than many of the exhibitions of fashion history that give the lion's share of attention to one gender or the other.

Little is intractable about gender and dress. At most times, men and women stand separate in their dressing preferences, yet we recognize a dynamic in fashion that grants the sexes a deliberate accord. In the eighteenth century, men were resplendent in lace trims and accents, floral waistcoats, and rich suits. In the 1830s, it might have seemed as if the shapes, textures, and choices in men's and women's apparel were coming closer and closer together. In the Victorian era, women accommodated their dress to the industrial black and heavy textiles that men in dark frock coats with bowlers and top hats had evolved by the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1860s, the man's three-piece suit was starting to emerge. At the beginning of the twentieth century, sportswear and separates were transforming the wardrobes of women and men and making them more alike. The Gibson Girl and her beau were both wearing starched shirts, wool blazers, and straw bowlers. In the 1940s, both men and women affected a slim-hipped, broad-shouldered swagger. By the late 1960s, the word unisex had entered the popular vocabulary in order to describe the wide-ranging instances of dress interchangeable as to gender. Yet we acknowledge the truism that in contemporary formal wear, the male defers to the grander display of the female.

We do not propose a specific system to govern the dress of men and women together. History affords no consistent pattern of gender match or appropriation, though men's clothing more often lends its specific types to women's than the other way around. As clothing is a constituent of social authority, we can rightly assert that a particular society attaches greater value to men's apparel. Even in contemporary dress, while womenswear borrows men's tailoring, the buttoning is still reversed.

Surely, God's instruction to Noah was meant to benefit propagation. However, no other animal on the ark benefits from the propensity to variety and expression that humans achieve through clothing.

Met Art in Publication

You May Also Like

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Citation

———. 1996c. Two by Two. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.