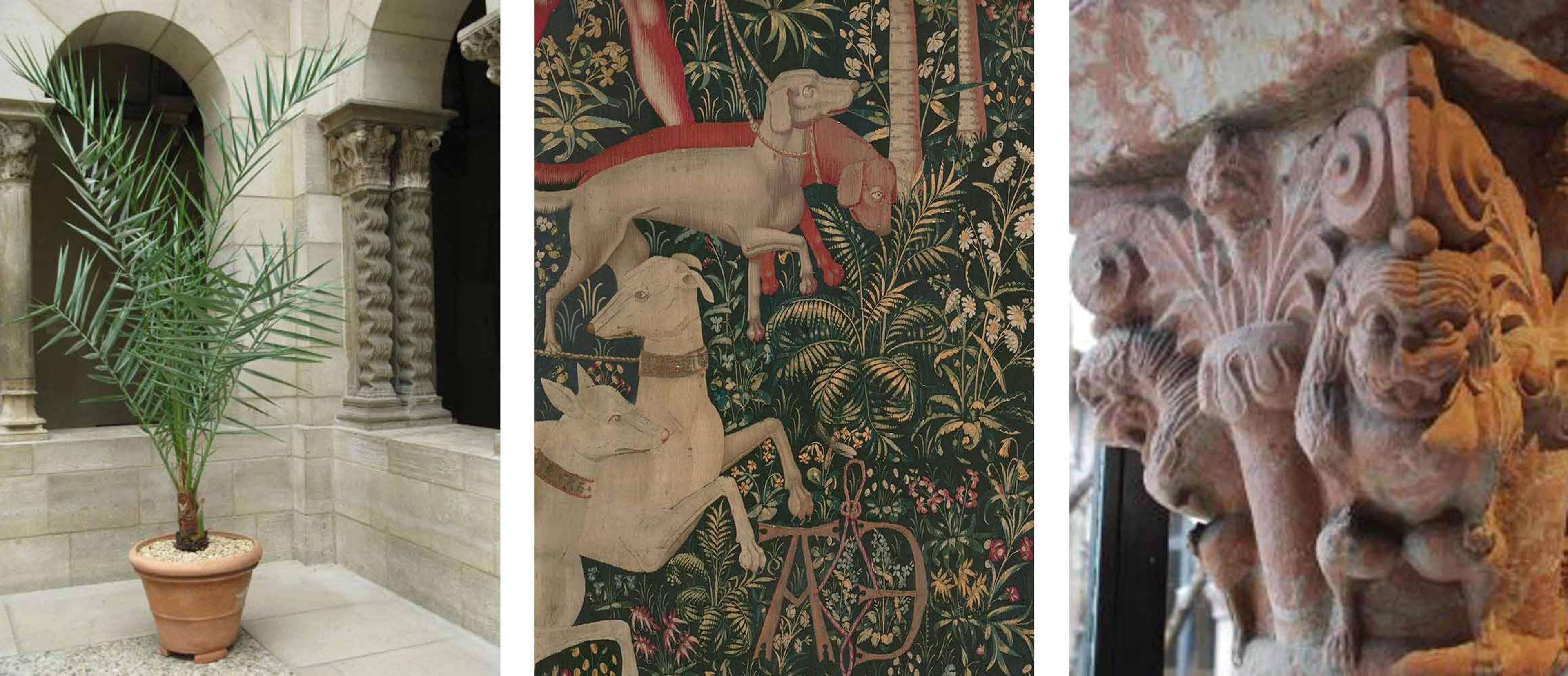

Above, from left to right: young date palm growing in a pot in Saint-Guilhem Cloister; a juvenile date palm represented in the northern European landscape of The Hunters Enter the Woods; a date palm flanked by lions in a column capital in Cuxa Cloister

A plant of ancient cultivation, grown for some five thousand years and with an equally long presence in art and architecture, the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) was and is both economically and symbolically important. Date palms have provided an important food, an intoxicating liquor, a sweetener, and a building material. Identified in the ancient Near East with the Tree of Life, the palm has both religious and artistic significance in Jewish, Islamic, and Christian tradition as a symbol of grace, elegance, victory, wealth, and fecundity and is frequently associated with Paradise in medieval and Renaissance art and literature. There are forty-two Biblical references to the date palm (Moldenke and Moldenke, Plants of the Bible, 1952). An emblem of victory in Greco-Roman tradition, the palm was adopted as one of the earliest and most important plant symbols in the Christian Church, and was an emblem of the martyred saints in their victory over sin and death.

This image of a palm tree flanked by lions from the west arcade of the twelfth-century Benedictine monastery of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa derives from a long artistic tradition. Palms and palm-derived decorative motifs were often employed in ancient Near Eastern and Classical architecture and continued to be used throughout the Middle Ages.

The palm is native from North Africa eastward to Asia Minor, Arabia, and Iraq, and has been introduced into many other places that enjoy a Mediterranean climate, including California, Mexico, and Australia. The botanical name of the genus is not thought to derive from the mythical bird, but rather from the Greek designation for Phoenicia (Anderson, German Herbals to 1500, 1984).

Although dates do not seem to have a wide application in medieval medicine, regimens like the Tacuinum Sanitatis recognize their value as a food stuff and recommend sweet, fresh dates as the best kind. Classified as cold in the first degree and dry in the second, fresh dates are said to be good for the intestines, although bad for the chest and the throat. The danger could be mitigated by eating the dates with honey (Luisa Cogliati Arano, Tacuinum Sanitatis: The Medieval Health Handbook, 1976).

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) is one of two medieval species of palm grown in pots at The Cloisters. The other is the fan palm (Chamaerops humilis).

The single-stemmed date palm takes thirty years to reach maturity, and can live two hundred years. The tree, which can attain a height of eighty feet and whose drooping fruit clusters can weigh as much as fifty pounds, has a long period of juvenility (Moldenke and Moldenke, Plants of the Bible, 1952). Thus we are able to grow young specimens of various sizes in containers for display, although none are mature enough to bear dates.

Date palms are dioecious, i.e, there are both male and female date palm trees. It appears that even in Mesopotamian antiquity, the need to bring the male and female flowers together in order to ensure good fruiting was recognized, although it would be many, many centuries before plant sexuality was understood. The Greek botanist Theophrastus records the ancient practice of dusting the fruit of the female palm with bloom cut from the male in order to ensure that the fruit persisted and ripened (George Sarton, "The Artificial Fertilization of Date-Palms in the Time of Ashur-Nasir-Pal B.C. 885–860", Isis, Vol 21, No. 1, 1934).

Photograph by Barbara Bell

The fern-like plants growing in the meadow in which the hunters and their dogs gather to hunt the Unicorn do not correspond to any European species of fern. E. J. Alexander and Carol H. Woodward, two botanists at The New York Botanical Garden who compiled a botanical key to the flora of the Unicorn Tapestries published in 1941, believed them to be young date palms that would have been reared from the seeds of dates imported from the East (Adolfo S. Cavallo, The Unicorn Tapestries, 1998). The date palm is not the only exotic species depicted growing alongside the native trees in the landscape of the tapestries; pomegranates are shown as well. While rare and unusual trees were planted in medieval hunting parks, neither of these two species would have been hardy in northern Europe. They may have been included for symbolic reasons.

The Hunters Enter the Woods (from the Unicorn Tapestries) (Detail), 1495–1505. French (cartoon); Southern Netherlandish (woven). Wool warp, wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts, 145 x 124 in. (368.3 x 315cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.1)