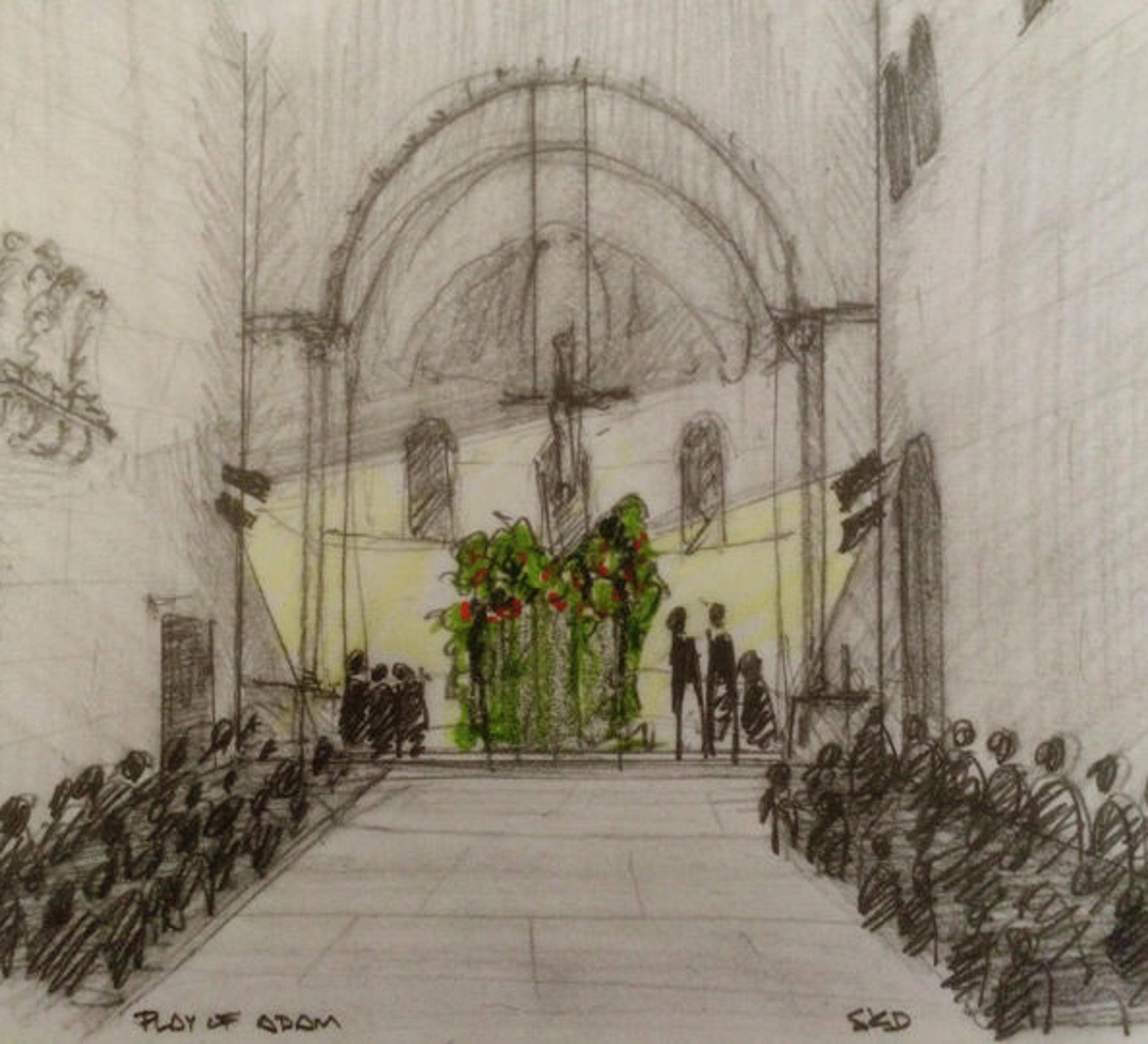

Rendering of The Play of Adam at The Met Cloisters. Set design by Stephen Dobay

"Behold, a virgin shall conceive in her womb and shall bear a son, and his name will be called Emmanuel . . ." —Isaiah, 7:14 [1]

The oldest medieval drama in any language, The Play of Adam portrays the familiar story of Adam and Eve, who were created by God and later succumbed to the devil's temptation, prompting their expulsion from Paradise. The plot of the 12th-century play continues with the heated sibling rivalry of Adam and Eve's children, Cain and Abel, and then introduces a series of Old Testament prophets who foretell the birth of Jesus. The last of these prophets, Isaiah, enters into a disputation with a skeptic who challenges his prophecy of the virgin birth.

This narrative, with its emphasis on the coming of Jesus Christ and the promise of salvation, probably derived from texts read during the Advent season in medieval Europe, making The Play of Adam an ideal theatrical experience for the weeks leading up to Christmas. Incredibly, only now is the play receiving its world premiere—having never been staged before—with four performances on December 17 and 18 at The Met Cloisters. The MetLiveArts production will be performed in a new English verse translation by Carol Symes, and will feature festive vocal and instrumental music appropriate to the season and the period.

Doorway, mid-12th century. From the church of Saint-Sulpice at Coulangé; made in Touraine, France. Limestone, 166 x 180 in. (421.6 x 457.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.878)

"Jol frai, sire, a ton Plaisir. Ja n'en voldrai de rien issir." ["I will act, my Lord, just as you say. I never want to go astray."] —Eve

Never before had a medieval play been scripted almost entirely in the vernacular. The Play of Adam was composed (we don't know by whom) in Anglo-Norman, a language spoken in northern France and England following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. Eventually that realm encompassed vast territories on both sides of the English Channel, which may explain why the play's sole (and incomplete) manuscript is now housed in Tours (Bibliothèque Municipale, MS 927), in the heart of the Loire Valley in central-western France.

"Let all characters be instructed . . . so that they should speak correctly and make gestures appropriate to the things about which they are speaking . . . let them neither add nor subtract a syllable, but pronounce everything confidently and say those things that ought to be said in the right order . . ."

Some of the most unusual elements of The Play of Adam are the meticulous stage directions that indicate, in great detail, how the production should be staged and enacted—which gestures the performers should use and how they should interact with one another within the playing-space. Some of the characters, especially the devils, are even instructed to interact with the audience, making the play a truly engaging experience for audiences. The whole point of the production is that the events of sacred history are unfolding in the immediate moment, with no barrier between the past and present or the actors and spectators. The only exceptions to this rule are the liturgical chants interspersed throughout the dialogue, which were originally in Latin; in the production at The Met Cloisters, they will be sung in English.

Doorway from Moutiers-Saint-Jean, ca. 1250. Made in Burgundy, France. White oolitic limestone with traces of paint, 15 ft. 5 in. x 12 ft. 7 in. x 55 in. (469.9 x 383.5 x 139.7 cm); Opening: 110 x 66 in. (379.4 x 167.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1932 (32.147)

"Then the figure should go to the church, and Adam and Eve should stroll about the place, openly delighting in Paradise."

The stage directions strongly suggest that the play be performed in front of a church portal in the midst of a bustling town square. The Met Cloisters, a museum dedicated to the art and architecture of medieval Europe, provides a unique venue for such a historical presentation. For example, the portal that originally provided the backdrop for The Play of Adam would have looked very much like the doorway from the Benedictine abbey of Moutiers-Saint-Jean, providing a ready-made elevated stage a few steps above the audience members, who would have clustered at the foot of the steps to watch the play unfold.

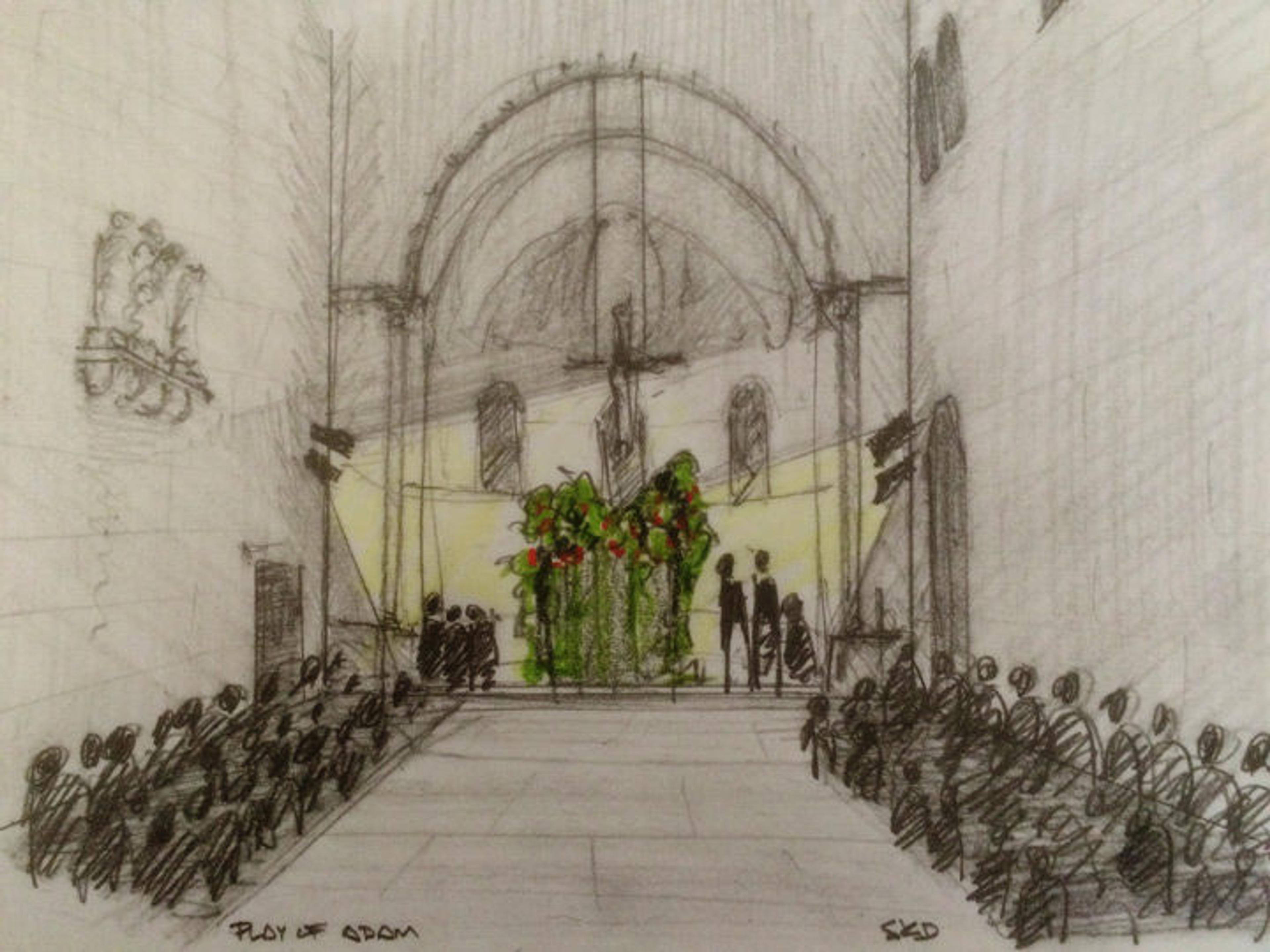

Rendering of Paradise for The Play of Adam, in the apse of the Fuentidueña Chapel at The Met Cloisters. Set design by Stephen Dobay

"Paradise should be set up in a prominent place . . . fragrant flowers and foliage should be strewn around. There should be various kinds of trees there, and fruits hanging from them, so that the place may seem very delightful."

In our production, Paradise will be set in the semicircular apse of the Fuentidueña Chapel, with a number of pedestals decked with plants such as English ivy, boxwood, holly, and bay laurel—all meant to invoke the verdant and lush landscape of Paradise, and all used by the horticultural staff at The Met Cloisters to decorate the galleries throughout the museum. In this way, the stage set of The Play of Adam is truly integrated with the artistic and decorative schema of the entire museum.

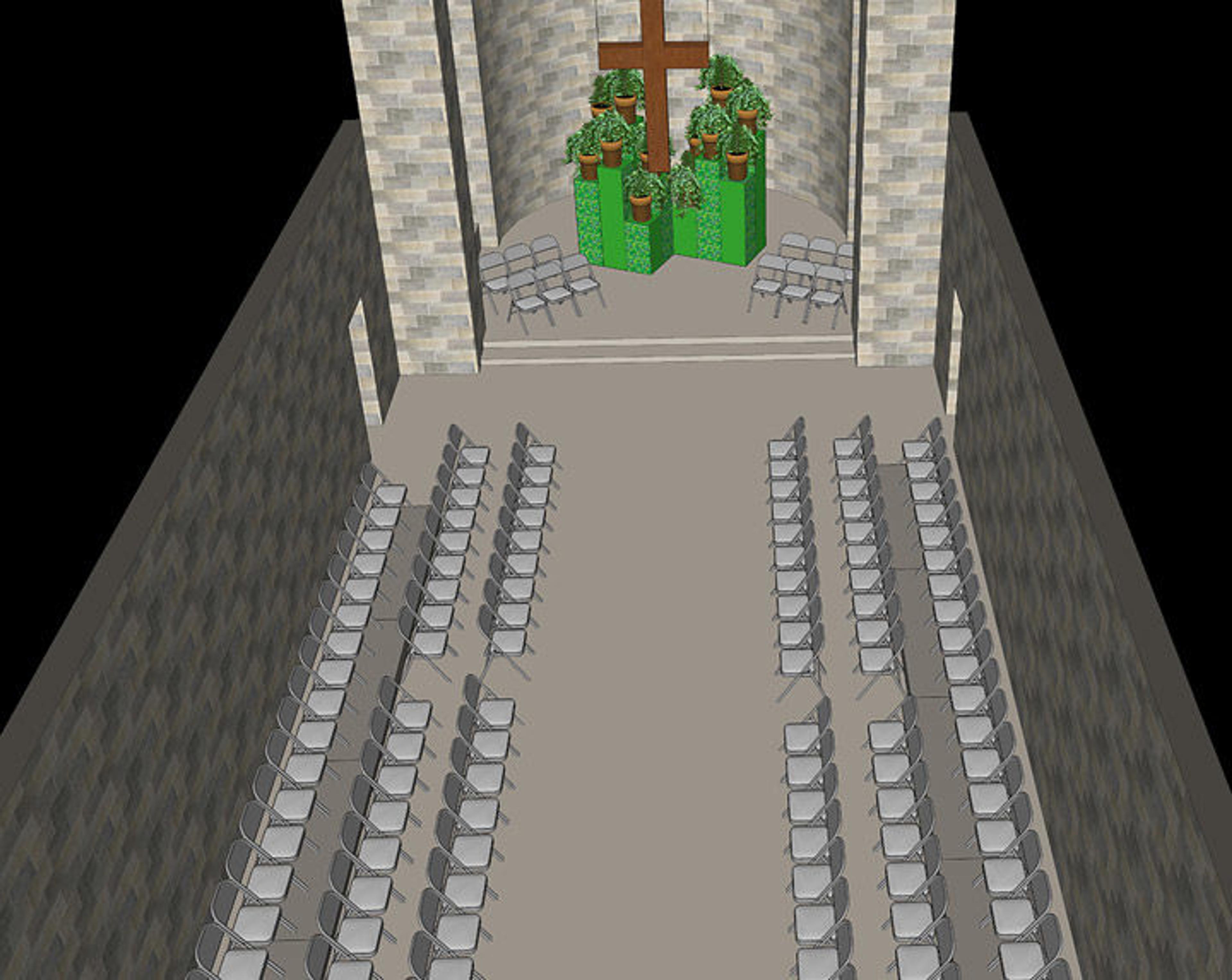

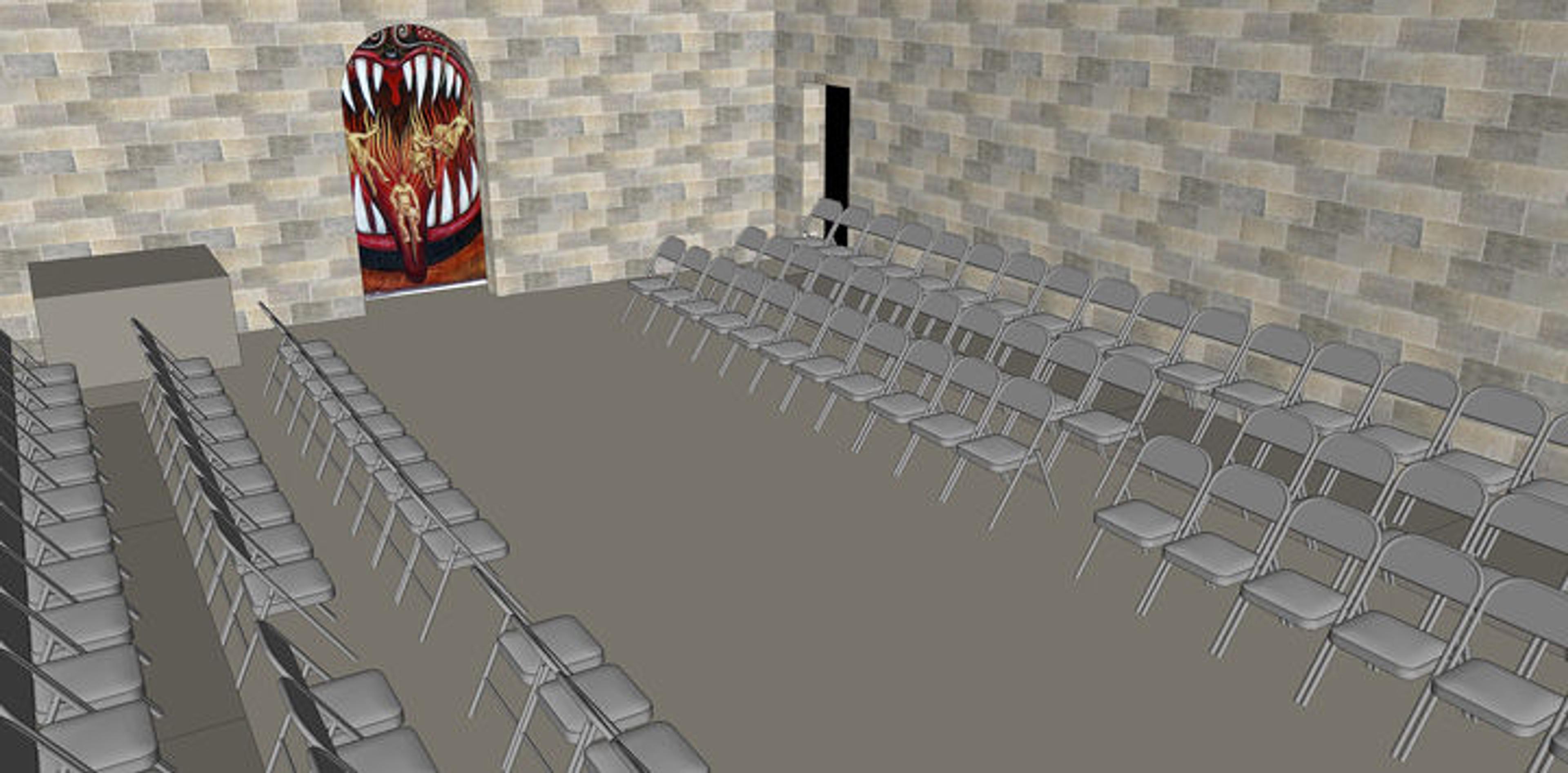

Rendering of the Hellmouth for The Play of Adam at The Met Cloisters. Hellmouth painting by Helen McCarthy; set design by Stephen Dobay

"The devils, coming out, will lead Cain to Hell, striking [him] very often . . ."

Suspended across the doorway to the chapel's entrance is a fearsome Hellmouth painted on fabric. It thus stands opposite Paradise in the chapel's apse, and together these two locations represent the extreme poles of the play's world. On the one hand, the Hellmouth bares its sharp teeth and is about to devour poor souls in its burning fire. The image's ferocity mirrors a 12th-century capital in the adjacent Saint-Guilhem Cloister carved with equally menacing and frightful grin, while the crucified Christ suspended above the apse represents the promise of mercy and redemption.

Capital (depicting the Hellmouth), late 12th century. From the abbey church of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, near Montpellier, France. Stone, 11 3/4 x 10 x 10 in. (29.8 x 25.4 x 25.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1925 (25.120.54)

Befitting the holiday season and true to medieval traditions, this lively modern translation of The Play of Adam enacts a timeless drama of human fallibility and resilience, and comically and poignantly addresses such universal themes as ambition and desire, loyalty and betrayal, the allure of wealth, and anxieties caused by rapid and uncertain social changes. We look forward to presenting the visual, aural, and aromatic pleasures of this play in the beautifully appropriate setting of The Met Cloisters.

[1] All translations and quotations in this post from Carol Symes's The Play of Adam in Broadview Anthology of Medieval Drama (2012), edited by Christina M. Fitzgerald and John T. Sebastian.

Related Links

Now at The Met: "Medieval Drama at The Cloisters" (September 5, 2013)

In Season: "The Portal of Villeloin-Coulangé at The Cloisters: Attribution After Eighty Years of Anonymity" (November 20, 2014)