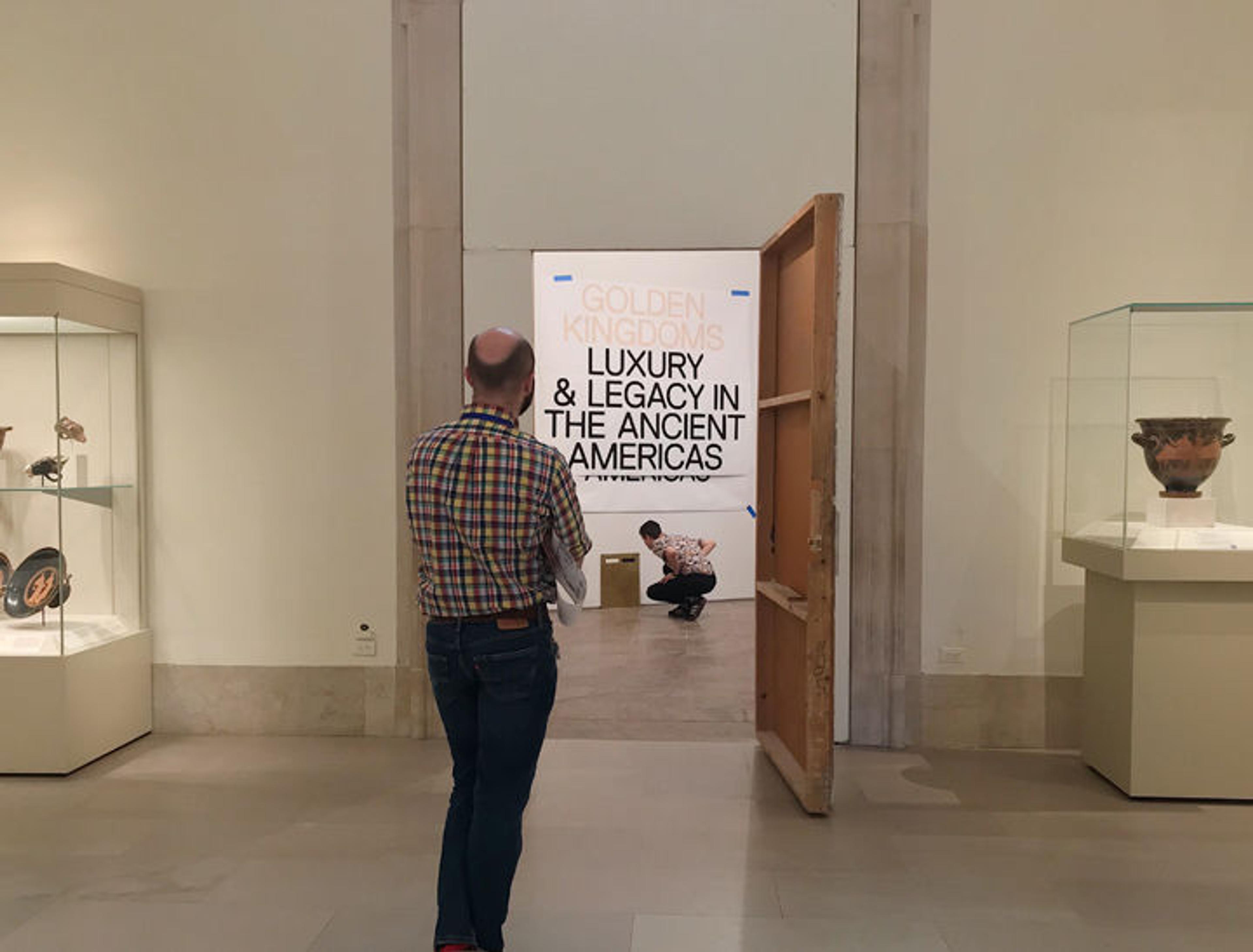

Assistant Curator James Doyle (foreground) and Collections Manager David Rhoads (background) examine the mock-up title in the entryway to the Golden Kingdoms exhibition. All photos by the author unless otherwise noted

«When you walk into an exhibition, you experience the sum of many parts—a final product that often belies the extraordinary number of phone calls, lengthy email threads, and late-night meetings held to ensure the smooth execution of a single show. For an exhibition that brings together more than 300 works of art, 52 lender institutions, and hundreds of colleagues from across Latin America, Europe, and the United States, Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas naturally has its share of moving parts. Beyond the literal size of the exhibition, Golden Kingdoms is also a thematically rich, multilayered show five years in the making, carefully conceived by curators Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter.»

As a curatorial intern here at The Met, I've been able to peek behind the metaphorical curtain and see all those inner workings of an exhibition kept hidden from the public's eye. To share some of the excitement happening behind the scenes, I present our blog readers with an in-depth look at this exhibition's design and installation, two major components of any successful show.

The Design of Golden Kingdoms

Exhibition Design Manager Daniel Kershaw (left) and Graphic Designer Mortimer Lebigre (right) review a floorplan of the gallery space.

Although I have always been fascinated by design, I came into the exhibition with only a hazy understanding of what this process entailed. Working with Exhibition Design Manager Daniel Kershaw (a.k.a. the mastermind behind the gallery spaces for Golden Kingdoms), I discovered a whole cosmos surrounding design work. Dan had envisioned the architectural elements of the exhibition, worked in collaboration with the curatorial team to place objects within thematic groupings, and incorporated a floor projection into the galleries with the help of a team from the Digital Department, all while keeping track of the ever-evolving display requirements for each object in the exhibition (that's 352 individual objects!).

Daniel Kershaw (far right) works with the digital and curatorial teams (including the author, third from right) to create a floor projection for one of the galleries in the exhibition. Photo by Joanne Pillsbury

After speaking with Dan about his experience designing Golden Kingdoms, I further learned that his work involves a steady progression of ideas that continues to build and change right up until the show opens to the public. In one of the exhibition's galleries, for example, the space around a large stone sculpture seemed wide enough on a two-dimensional floorplan, but proved too tight for comfort when measured in the actual gallery. Dan had to rearrange a few of the cases to make sure that both the objects and the visitors would fit comfortably in the gallery space—no easy feat!

Left: Daniel Kershaw (top of ladder) and Mortimer Lebigre (bottom of ladder) test a mock-up of the title banner.

Although gallery and case design alone seemed endlessly complex to me, I soon saw that graphic design was another intricate—and no less crucial—element necessary for the success of the show. Graphic Designer Mortimer Lebigre led the curatorial team on gallery walkthroughs to test mock-up renderings of the design elements and to see how these components physically fit within the galleries. During these meetings, I learned that Mort's work—which deals with wall texts, object labels, contextual maps, and more—significantly affected the overall look and feel of an exhibition. The minute details, such as the size, layout, and placement of these texts and images, have a direct hand in creating a sense of cohesiveness within a gallery space that subtly situates and directs the visitors. It was fascinating to see just how these components came together, giving both meaning and visual impact to the show.

The Installation of Golden Kingdoms

Assistant Conservator Caitlin Mahony studies a Maya cylinder vase from the collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.

Even before the loaned works arrived at The Met, I could see how the installation of more than 300 objects—most of them international loans with detailed mounting, handling, and display requirements—could easily become the stuff of nightmares. One small setback, such as an unwieldy object that requires more time to install than expected, could create serious complications for an already packed agenda. Even the installation schedule itself, which describes what loan objects will arrive on which days and when these objects will be installed into their cases, required many days to draft and finalize.

An exhibition as large in size and scope as Golden Kingdoms also requires extensive interdepartmental and international collaboration, particularly during a tight three-week installation period. Once the objects began arriving at the Museum with their couriers, many of whom had traveled great distances to look after the national treasures of their respective countries, the works of art were unpacked from their crates, documented by the registrars, and condition-checked by a team of conservators who evaluated the state and stability of the loaned works.

Left: Conservator Christine Giuntini puts the finishing touches on the display of a 17th-century miniature tabard created in Bolivia or Peru.

When it finally came time for the actual installation of the objects into their cases, a delicate choreography among couriers, installers, mount-makers, technicians, and carpenters seemed to ensue. Heavy stone objects further required the handiwork of machinists and riggers, who maneuvered the sculptures, some weighing over 1,500 pounds, into their designated locations within the galleries. Meanwhile, the lighting team began working their magic, modifying the color and brightness of the light to bring out the best qualities of each object. They say it takes a village to raise a child; I think the same can be said for an exhibition!

Before I joined this extraordinarily dedicated team, I, too, frequently stepped into an exhibition without thinking of the vast number of people that must have worked on the show or the extensive amount of time poured into every detail of the galleries. Now that Golden Kingdoms is nearly ready for the public opening on February 28, I've come to realize that at the end of the day, the exhibition team works to produce this very result: to have visitors see and enjoy the works of art without becoming distracted by the cases, the font of the wall texts, or the object mounts in the show. But lest you think it all looks too easy, I'm here to assure you that this exhibition, like many before and after it, is much more than what meets the eye.

Related Content

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from February 28 through May 28, 2018

See more digital content related to Golden Kingdoms, including a walkthrough of the recent exhibition in English and in Spanish.

Purchase a copy of the exhibition catalogue in The Met Store.