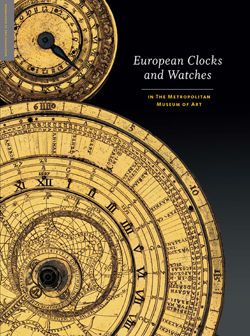

Watch in the form of a human skull

Watchmaker: Isaac Penard Swiss

Casemaker: probably the Firm of Moulinié, Bautte & Moynier Swiss

Not on view

A sundial motto, “Oh remember how short my time is,” from a verse in the Old Testament (Psalms 89:47) explains the form of this watch. Reminders of the imminence of death were appropriate to an age when wars and plagues carried off great numbers of people. Numerous vanitas can be found in the seventeenth century; a painting from 1630 in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague (fig. 28) by the Dutch artist Pieter Claesz (1596/97–1660), for example, depicts both a skull and a watch, as well as other symbolic reminders of the shortness of human life.

Among those who subscribed to the Calvinist form of Protestantism there was an inherent focus on time, and watches counted the hours. The skull-shaped watch was one of the products of this tradition, and while some of these watches were made in southern Germany,[1] more of them seem to have been made in seventeenth-century Blois, a center of Calvinist, or Huguenot, watchmakers in France.[2] But the theocracy established in 1541 by John Calvin (1509– 1564) became the prime source of watches with cases in the shape of human skulls in seventeenth- century Geneva.[3] The earliest of these watches is thought to have been made by Martin Duboule (1583–1639) and is now in the collection of the Musée du Louvre.[4] A watch in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection (17.190.1574) made by Pierre Landré of Blois (born 1610–active 1637) [5] is not unlike the Duboule watch, and both are believed to be from about 1630. Skull watches continued to be made throughout the eighteenth century in Geneva, and the local firm of Moulinié, Bautte and Moynier (partnership recorded 1808–21) was still making them in the early years of the nineteenth century.[6]

Isaac Penard (1619–1676), once thought to have been a watchmaker in Blois,[7] is now known to have been born in Geneva and apprenticed in 1632 to Jaques Sermand (1595–1651), a noted maker of so-called form watches, or watches in fanciful-shaped cases. Penard married in 1644,[8] and while the actual date when he became a master in Geneva is not known, it was usual for a craftsman to marry only after becoming a master and establishing a workshop. The misattribution to Blois was easily made because Genevan masters were required to engrave only their names on their watch movements and not their place of origin. The Museum’s Penard watchcase consists of a hand-raised silver cranium with a riveted loop and ring at the top to which a cast-silver front plate and facial structure has been brazed. The lower skull and jaw, a separate piece of cast silver that displays the naturalistic details of a human skull, is hinged to the back of the cranium and can be opened to reveal the dial of the watch inside. The catch is a separate piece that is brazed to the back of the teeth in the lower jaw. The dial plate is brass and has a repeating leaf design that encircles a silver chapter of hours (I–XII), with the half hours marked by sprigs. A ring of floral ornament and a single brass hand issuing from a central flower-like ornament completes the design.

The movement is also hinged to the back of the cranium. It consists of two oval brass plates held apart by four baluster pillars; three pillars are pinned to the back plate of the watch. The movement is spring driven with a gut fusee, and it has three wheels ending in a verge escapement. The back plate was originally fitted with a ratchet and click regulator for the setup of the mainspring. Only the openwork click and the ratchet wheel remain. The screwed-on balance cock is ornamented with openwork floral scrolling, and the engraved signature “Isaac Penard” appears below the cock.

The movement of this watch has had a difficult existence. The spring for the click of the setup of the mainspring is missing, and the ratchet wheel has bent and broken teeth. The contrate wheel in the going train is probably a replacement, and the escape wheel, verge, and balance of the escapement are particularly clumsy replacements. The present balance wheel is a solid disk that makes the watch useless as a timekeeper. In addition, the end of one of the pillars has been cut off to accommodate the disk. The case for the watch movement is a replacement for one that may or may not have been skull-shaped. It closely resembles the case of a skull watch with a movement by Moulinié, Bautte and Moynier in the collection of the Musée International d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland,[9] and it was probably made about the same time. The La Chaux-de-Fonds watch is the product of a partnership between Jacques- Dauphin Moulinié (active 1793–1828), Jean François Bautte (1772–1837), and Jean-Gabriel Moynier (1772–1840).[10] As Moulinié and Bautte began as watchcase makers, it is probable that the case and the movement of that watch was their work. The dial is quite different from that of the Metropolitan Museum’s watch, and the niello-ornamented dial of the latter may be the product of an even later period, when it was made to fit the Penard movement and evidently to create a watch to be sold to a nineteenth-century collector. Nonetheless, the case remains a fine example of the period.

According to George C. Williamson, the historian and author of the Morgan collection catalogue, the watch was part of the collection of the British banker Frederick George Hilton Price, who had acquired it from the British collector J. Dunn Gardner.[11]

Notes (For key to shortened references see bibliography in Vincent and Leopold, European Clocks and Watches in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015)

[1] For German examples, see one in the British Museum, London (inv. no. 1874,0718.41, signed “J C Vuolf”); this was probably Johann Conrad Wolf, who was recorded in Donauworth in 1638. See Thompson 2008, pp. 46–47. Another with an automaton jaw is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; see Maurice 1976, vol. 2, pp. 61–62, no. 447, and figs. 447a, b.

[2] Fourrier 2001, pp. 38–46.

[3] Jaquet 1948c; Jaquet and Chapuis 1970, pp. 23–24.

[4] Inv. no. OA 7036. See Cardinal 2000, p. 80, no. 51.

[5] Acc. no. 17.190.1574. For Landre, see Tardy 1971–72, vol. 2, p. 348; Fourrier 2000, p. 39.

[6] Meis 1980, pp. 138–39.

[7] Williamson 1912, p. 13, no. 8.

[8] Jaquet 1948a; Gibertini 1964, p. 239.

[9] Inv. no. I-2. See Musee International d’Horlogerie 1974, p. 39; Cardinal and Piguet 2002, pp. 230–31, no. 276.

[10] Pritchard 1997, vol. 2, p. m-108. See also Patrizzi 1998, pp. 285, 96, 286, respectively.

[11] Williamson 1912, p. 13, no. 8.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.