Corpus from a crucifix

Probably Unknown

Not on view

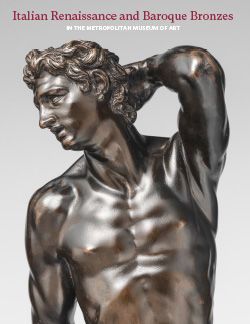

This finely modeled gilt-bronze figure of the dead Savior (Cristo morto) exudes pathos. The face is slack in death, with unseeing eyes and open mouth. The conspicuous ribcage and sinewy arms convey Christ’s torment. The billowing loincloth, as if whipped by a sudden wind, is a poignant reminder of the barren setting of his lonely ordeal.

The figure was cast in a relatively pure tin bronze in four sections: each arm, the torso with the head, and the legs integrally with the perizonium. The four pieces were fastened with typically inserted sleeve joins fixed by cross-pins.[1] The same high level of technical finesse is evident in the thin, even walls, at the virtual minimum for traditional bronzework (e.g., no more than 1.3 mm thick at the wound on the back of the proper left hand). Thus, despite its height, the corpus is strikingly lightweight. There are no cast-in repairs, although there is considerable fine porosity, which necessitated a great many screw plugs. Details such as the long curly hair and unruly tufts of beard were skillfully rendered. The gilding was applied using sheets of gold leaf after the bronze surface was “quickened,” or amalgamated, with mercury. The back was perfectly finished. The corpus had been mounted on a massive ebonized cross (inscribed “I.N.R.I.”) and affixed with four nails.

There is no literature on our bronze beyond the auction catalogues of the 1940s, which place it as Italian, early seventeenth century, a chronology John Goldsmith Phillips moved to the second half of the seicento.[2] Stylistically, nothing about the work definitively or exclusively says “Italian,”[3] and Richard Stone notes that the technical facture cannot be specifically identified with Italian foundry practices.[4] On the one hand, in pose our Dead Christ is reminiscent of Alessandro Algardi’s bronze corpus in the Franzoni chapel, San Vittore e Carlo, Genoa, which also has four nails.[5] Apart from Algardi, this detail was uncommon in early modern Italy, where the Jesuits’ three-nail-rule prevailed.[6] On the other hand, certain features of the head (the beautiful corkscrew curls, for instance), the inclination of the arms, the crisply modeled loincloth, together with the four nails, suggest a provenance north of the Alps, perhaps Southern Germany.

A promising direction to explore is that of a German artist in Italy. The silversmith and caster Johann Adolf Gaap is one such case.7 Born and trained in Augsburg, Gaap worked in Rome and died in Padua in 1724. The distinctive features of our corpus—the slack mouth, heavy eyes, and T-configuration of the nose, nasal root, and eyebrows—are seen in the faces of Gaap’s Personification of Charity, a silver relief for the Throne of Saint Feliciano in Foligno Cathedral (figs. 182a–b).8 The throne design was provided by the Jesuit painter and architect Andrea Pozzo, but the figures’ features reflect Gaap’s personal practice. This hypothesis requires more investigation, but it is a first step toward rediscovering a corpus that, given its high quality and stylistic peculiarities, merits a deeper look.

-FL

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. These are also sometimes referred to as Roman joins or joints. Radiographs show that the hollow arms were cast with a slightly narrower tubular section that was inserted into an opening at the shoulders and pinned. The perizonium was cast with a narrower upper section that was inserted into the lower torso. This join was reinforced with an internal rectangular gusset plate. R. Stone/TR, May 4, 2011.

2. February 1950, ESDA/OF.

3. This was confirmed in an email from Jennifer Montagu, August 17, 2019.

4. R. Stone/TR, May 4, 2011.

5. See Bruno and Sanguineti 2013.

6. On the dispute about the number of nails, see Mâle 1932, pp. 270–73. On the case of Algardi in particular, see Montagu 1999a, p. 166 n. 33. For a recent discussion of the four nails in the context of Algardi’s workshop, see Denise Allen in Wengraf 2014, p. 240 n. 21.

7. On Gaap, see Berliner 1952–53; Kerber 1965; Lipinsky 1981; Montagu 1996, pp. 136–41; “Gaap, Johann Adolf,” in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, 1998), vol. 50.

8. Montagu 1996, pp. 137–38.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.